By mid-March 2020, the World Health Organization had declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, the university had closed for the rest of the semester and the future seemed fraught with uncertainty. To make matters more complicated there was no vaccine yet for the novel coronavirus.

Just a year later, we have not one, but more than a dozen COVID-19 vaccines in use globally, with more being developed.

Despite the good news vaccines bring in combating the virus, vaccine hesitancy — the delay or refusal to accept vaccination, despite services being available — is a concern.

What a journey vaccine development has been

From the initial stages, trials and phases to where we are now, the vaccine development took those watching closely on quite a journey. Today, COVID-19 vaccines are being deployed around the world. In Canada, over two million people, above six per cent of the population, have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Nationally, the government has stated that their plan is to make the vaccine available to everyone who wants one by September. While this timeline is subject to change depending on vaccine stock and each province’s immunization plans, most Canadians will likely be offered a chance to get vaccinated in the coming months.

Vaccine hesitancy, caused by misinformation, lack of knowledge, mistrust and fear around vaccination, remains an important roadblock to the goal of vaccinating as many Canadians as possible.

As the COVID-19 vaccine rollout has ramped up, so has misinformation about the vaccine and its side effects.

This is already having an impact on vaccine distribution. Communications firm Edelman Canada found that sixty-six percent of Canadians are willing to be vaccinated within the year. The survey identified Canadian’s eroding trust in scientists, CEOs and journalists as a factor behind this statistic. This number falls below what is needed to achieve herd immunity.

Misinformation has always been dangerous. However, when vaccines are one of the most promising tools to see us out of the pandemic, misinformation is deadly. It breeds and sustains vaccine hesitancy and may be the reason why someone decides not to get the vaccine.

To combat this, efforts are underway to build confidence in the vaccines, including explaining the science behind them. The federal government, for example, is investing $64 million in COVID-19 vaccine education campaigns. Perhaps knowing the science and logistics driving the vaccine might reassure and encourage more Canadians to get vaccinated and reject misinformed vaccine narratives.

The logistics of the approved COVID-19 vaccines in Canada

Currently, there are four authorized COVID-19 vaccines in Canada: Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, AstraZeneca and Janssen.

Moderna is an American pharmaceutical and biotechnology company, focused on developing vaccine technology based on messenger RNA to kick-start production of therapeutic proteins in cells.

In Canada, the Moderna vaccine has been approved for people of age 18 and older. For the vaccine to work best, an individual requires two doses that are one month apart. From studying about 30,000 participants, the vaccine has shown to be 94.1 per cent effective in preventing COVID-19, starting two weeks after the second dose.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is a partnership between the American pharmaceutical company Pfizer and the German based biotechnology company BioNTech.

In Canada, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is approved for people over the age of 16. For the vaccine to work best, it also requires a second dose, 21 days later after the first. Based on studying about 44,000 participants, this vaccine was found to have 95 per cent efficiency in preventing COVID-19, starting one week after the second dose.

The AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine was co-developed by the University of Oxford and Vaccitech. The vaccine is manufactured by AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish pharmaceutical and biotechnology company.

In Canada, the AstraZeneca vaccine has been approved for people of age 18 and older, and requires two doses for greatest protection. The second dose can be taken four to twelve weeks after the first one. It is shown to be about 62 per cent effective in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 disease, starting two weeks after the second dose.

The Janssen vaccine is developed by Janssen Biotech Inc., a Janssen Pharmaceutical Company of Johnson & Johnson.

In Canada, the Janssen vaccine has been approved for people of age 18 and above, and it is a one-dose vaccine. From studies of about 43,000 participants, this vaccine was shown to be 66 per cent effective in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 disease, starting two weeks after vaccination.

Scientists say the percentage of effectiveness should not be used as a tool to directly compare the different vaccines. It is not a fair comparison because each vaccine was tested in different populations, different points in time and with different COVID-19 strains circulating.

The age restrictions for the vaccines are because the vaccines’ safety and effectiveness have not been established yet in people younger than the age restriction given.

Why vaccinate in the first place

The human immune system is marvelous in protecting against infection and fighting illness. It also remembers infections so the next time around, it can act more quickly. Vaccines make use of the immune system’s capacity to remember previously encountered infections.

The first time a person is infected with a virus, their immune system can take days or weeks to develop the tools needed to fight the infection. However, afterwards the immune system will remember the infection and how to protect the body against it through memory cells.

If you encounter that same virus again, the few memory cells dedicated to that specific virus activate, and the immune response, including antibody production, is quicker.

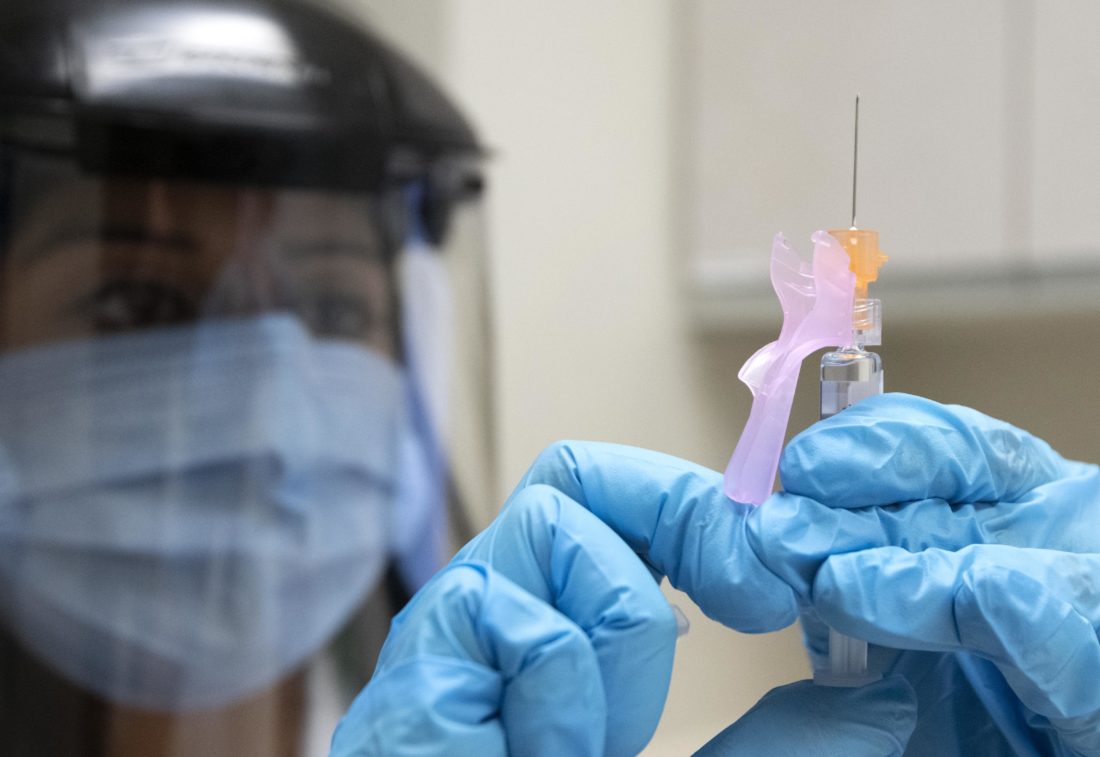

Vaccines help in developing immunity to viruses without having to go through the illness. After getting the shot, or shots as the case may be, immunity can take weeks to build. Some people experience symptoms like fever after vaccination, which are normal and indicate the body is building immunity.

Mechanism behind COVID-19 vaccines

Some of the COVID-19 vaccines differ from traditional approaches to vaccine development, in which developers use weakened or inactivated versions of pathogens. Vaccines for diseases like measles, mumps and rubella use a weakened form of the virus. The viruses used in these vaccines do not cause disease, but they do start an immune response, leading to the creation of antibodies to fight the virus, if encountered again.

While all COVID-19 vaccines aim to prevent the disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, their mechanisms are different. The Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech are mRNA-based vaccines while the AstraZeneca and Janseen vaccines are viral-vector-based.

Scientists began creating viral vectors in the 1970s and they have been used in vaccines, gene therapy and cancer treatment since then. Viral vectors have been studied for decades globally and have been used for infectious diseases like the flu, HIV and Zika.

Viral-vector-based vaccines use a different, harmless virus, the vector, to transport a set of instructions to the body’s cells. Think of the vector as a delivery vehicle.

The Janseen and AstraZeneca vaccines use adenoviruses as a viral vector. Adenoviruses cause the common cold and they come in many different types. They have been used for decades to deliver instructions for protein production to the cells.

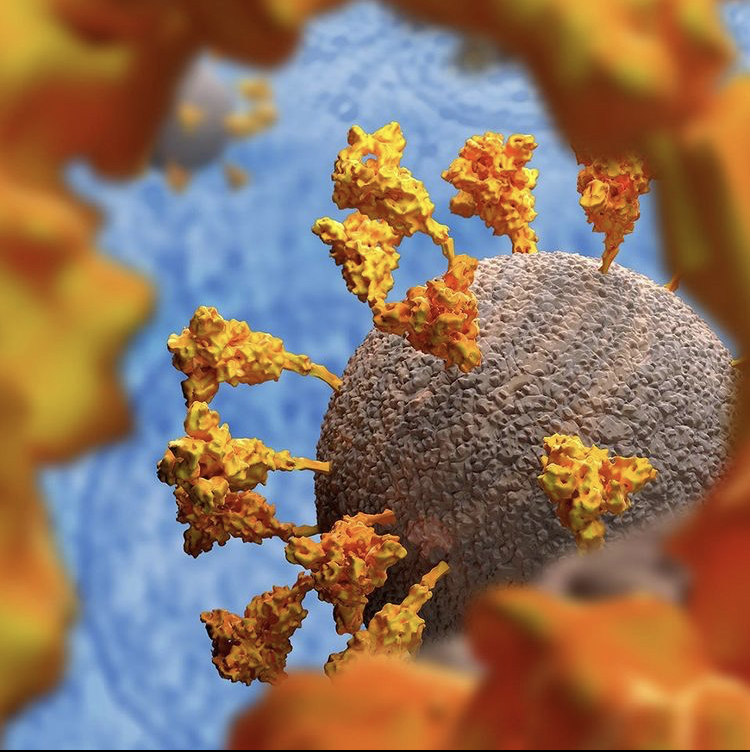

The vector enters cells and delivers genetic instructions that direct the cells to produce the spike protein found on the surface of the virus causing COVID-19. The cell’s own machinery is used to make this protein. It should be stressed that this is a harmless piece of the virus.

After making copies of the protein and displaying it on the cell’s surface, the body’s immune system will recognize the protein as non-self. After all, our bodies don’t naturally produce spike protein. This will then set off a series of reactions that lead our bodies to producing immune cells that will remember how to fight the virus.

mRNA vaccines are a new approach to developing vaccines against infectious diseases. However, scientists have been studying mRNA vaccines for many decades, including for the flu, rabies, Zika and for cancer treatment. There is a particular interest in mRNA-based vaccines because they can be made in a lab using available materials, therefore speeding up the vaccine production process.

mRNA is a molecule, found in cells, that contains the instructions for making proteins. The COVID-19 mRNA vaccines contain the genetic instructions to make the spike protein, essentially teaching the cell how to make the protein.

After the protein is made, the cell destroys the instructions and will display the protein on its surface. Similar to the vector-based vaccine mechanism, the immune system recognizes the protein as not being from the body and begins to mount an immune response.

Despite taking different approaches, all vaccines share the same goal. Their differences are based on the fact that cells require mRNA as a template to make proteins. The viral-vector-based vaccines require the genetic material to be transcribed to mRNA and then made into protein. The mRNA vaccines deliver instructions in mRNA form and do not require that transcription step.

Next steps

We live in a time when the potential of vaccines to prevent illness and save lives has never been greater. Yet, harnessing that potential requires people taking vaccines, which depends fundamentally on people’s confidence in vaccines. The mission to build trust in the COVID-19 vaccines starts with informing ourselves about the logistics and mechanisms behind them.

Leave a Reply