Work is — for better or worse — intrinsically linked to much of human existence. Everyone needs a source of money, and work, in some form, is the answer. It is this universality of work that makes having discussions about it so important.

Safety at work is crucial not only because the well-being of workers is important but also because — in most cases — the only thing a worker should be trading for wages is labour, not their well-being. Injuries can impact anyone’s work and life, and for students, an injury can impact schooling.

In a poll conducted on the Sheaf’s website about workplace injuries and safety, 42 out of a total of 68 respondents said that they work during the school year and 65 out of 67 stated that they work during the summer. While this is not a representative portion of the student body at the University of Saskatchewan, it is likely safe to say that a majority of students have some sort of experience with wage labour.

One such student is Meagan Kernaghan, who is working on both a Bachelor of Education and a Bachelor of Fine Arts. Kernaghan has had jobs in a variety of sectors, from service jobs and sales to manual labour work as well. She shares one of her experiences with an unsafe work environment.

“I did have one job that was sort of carpentry/ construction work that didn’t have really great safety measures in place,” Kernaghan said. “It’s a really uncomfortable work environment where you’re asked to do something that either you don’t know how to do, with a machine you’re not super sure how to use or without the proper safety equipment.”

Alongside this general overview of that particular job’s work environment, Kernaghan has a story of unsafe work she was requested to do.

“I was asked to climb a scaffold once without a harness — which is not safe, in case you didn’t know. I didn’t because I’m conscious of my own safety, but it was a weird request,” Kernaghan said.

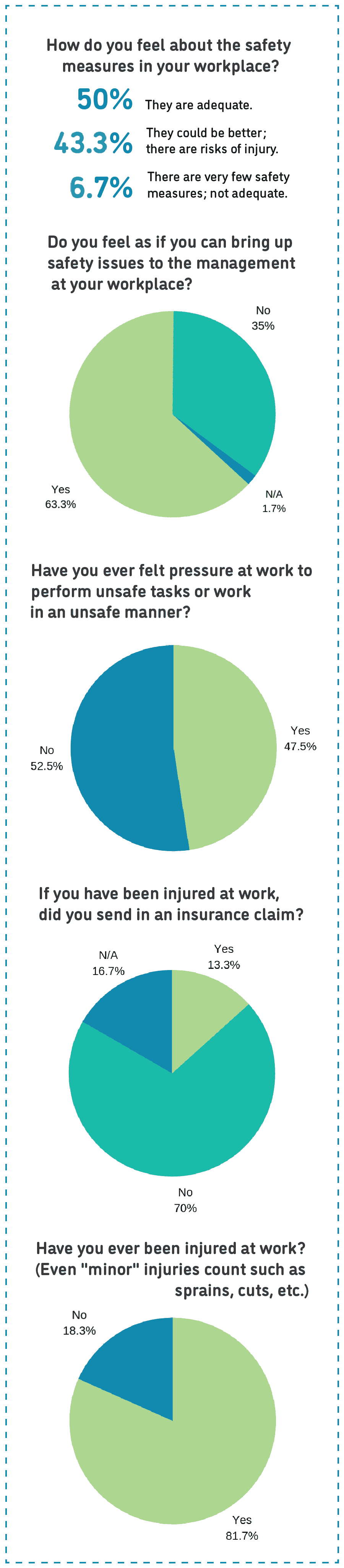

Comparing this story to the poll results illustrates that this is not an uncommon experience — with 29 respondents stating that they too had been pressured to perform a task that they felt was unsafe or to work in a manner that was unsafe compared to 32 respondents who said they had not.

Having done both unionized and non-unionized work, Kernaghan has ample experience with the safety conditions for both types of employment.

“In most cases, when you’re working when you’re not a union, your own safety sort of falls on you,” Kernaghan said. “If you don’t feel something is safe, don’t do it. It’s usually your own decision making to go, ‘Oh, I should probably wear gloves to do this, or I should wear a hard hat.’”

On the other hand, Kernaghan explains the difference she has encountered that comes with working under a union.

“In a union, safety is taken very seriously. You are not allowed on site without your correct personal protective equipment, and you are not allowed to do your job until you have shown that you can do it safely — and you’re ready to do it safely. It’s a totally different environment,” Kernaghan said.

Building on the differences between unionized and non-unionized work, Kernaghan says that there is also a difference between the two in terms of injury documentation — including filing to the Workers’ Compensation Board.

“As someone who has filed WCB and workplace injury forms both with a union and without, my union … said, ‘What was the underlying cause of this injury? How can we prevent it from ever happening again? What steps are we going to take as an employer to make sure that this never happens again?’” Kernaghan said.

Kernaghan further explains the difference she found in her non-union work.

“Usually, if I was injured somewhere that wasn’t a union, they just went, ‘That sucks — what a bummer. Don’t do that again, I guess, and we’re never gonna think about it ever again.’ Totally different,” Kernaghan said.

On the topic of bringing up safety matters to higher-ups, a majority of poll respondents responded “yes” when asked whether they felt that they could bring up their safety issues to the management at their workplace. The vote breakdown came to 38 yes votes, 21 no votes and 1 vote for not applicable.

Being able to bring up safety issues to management is integral to a safe workplace. That being said, there is only so much that the individual can do for their safety — a concept that Kernaghan also speaks to.

“You’re not 100 per cent responsible for your own safety. If you haven’t been trained properly or you don’t know that there is someone working above you, so you’re not wearing a hard hat, you should be made aware of that fact,” Kernaghan said. “You are responsible for everybody else’s safety, though. As individuals, we do have to take some responsibility.”

On the topic of risk and responsibility, Kernaghan talks about pay and how, at times, pay can be more if there’s a greater risk to the worker. She applies this idea to her own experience of arena rigging, which essentially consists of building points into the ceiling of an arena. These points are used to hoist up concert lights, for example.

“Often, you will be paid more the more you are at risk, so if you are doing work that has a high level of risk in the same field, you are generally paid more,” Kernaghan said. “[With] rigging, ground riggers are paid a little bit less than up-riggers, to start — so the people on the ground versus the people in the air — because the idea is that the people in the air might fall.”

There are, of course, times when the pay does not feel adequate for the amount of strain being put on your body. It’s not always about the bigger risks, Kernaghan explains, but what she calls casual injury.

“[There’s] sort of day-to-day, regular injuries that are like ‘I don’t need WCB’ or ‘I don’t need to go to the hospital, but I have a big ol’ splinter in my leg, and that sucks,’ and it’s just the amount of casual injury [that] doesn’t meet the rate of pay in some cases,” Kernaghan said.

She goes on to explain her concept of casual injuries and how they relate to how she feels about her pay in a given job, using the job with the splinter as an example.

“My leg’s bleeding a little bit, but I get paid $18 an hour, so I’m not gonna complain about it, whereas if I get paid minimum wage, I might complain about it,” Kernaghan said.

In the online poll, respondents were asked whether they had ever been injured at work — with a stipulation included to count any minor injuries as well, such as cuts or scrapes — with 49 respondents voting “yes” and only 11 voting that they had never been injured at work.

Injuries do not have to be massive or life changing in order to be important. Smaller scale injuries, such as sprains and pulled muscles, can still have an impact on your life. In this vein, a job doesn’t have to be what is typically viewed as dangerous — like construction or other manual-labour-intensive sectors — to have safety issues.

Kernaghan has her own example of an injury she received in the service sector — a type of employment often associated with students — that illustrates this concept.

“Working at Starbucks, I burned my fingers all the time, and I actually threw out my neck because a box fell on my head because it was stored improperly. It was stored touching the ceiling, essentially, and it fell,” Kernaghan said. “And that was at Starbucks — that wasn’t even somewhere you think there is an element of risk.”

Judging by the prevalence of injuries reported in the poll and the stories related by Kernaghan, injuries can seem like an integral part of work. You cut your hand or sprain something and think nothing of it, but what sort of work environment do you have when you are not only trading your labour and time but also bits and pieces of your well-being as well?

If you feel unsafe at work, you can report unsafe working conditions to Occupational Health and Safety at 1-800-567-7233.

—

Jack Thompson / Sports & Health Editor

Graphics: Jaymie Stachyruk / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply