When looking at the food in a person’s life, the questions shouldn’t necessarily stop at “What is enough?” Rather, in order to discover what food security at the University of Saskatchewan looks like — and what it truly means — one has to look at the issue from several angles.

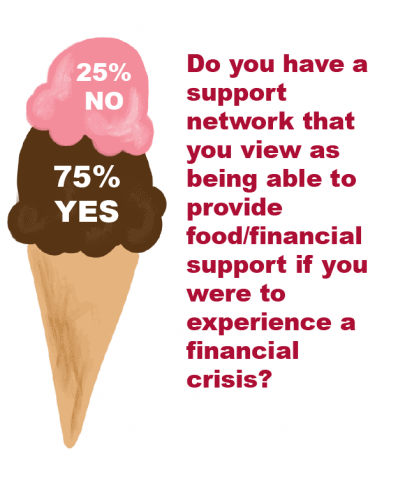

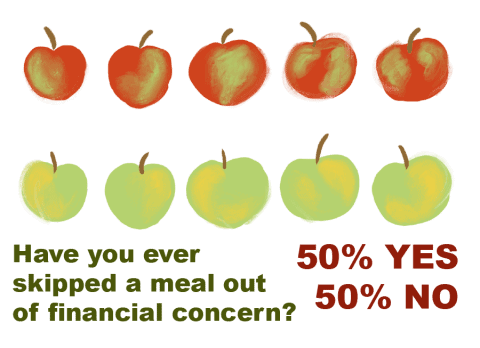

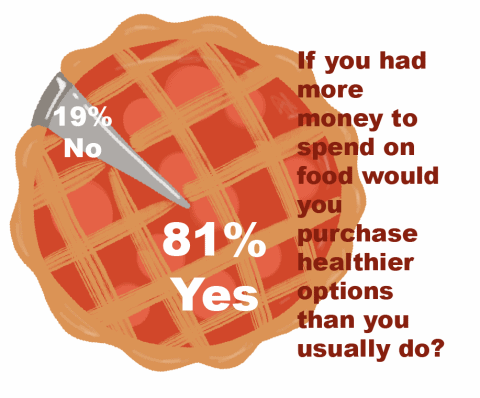

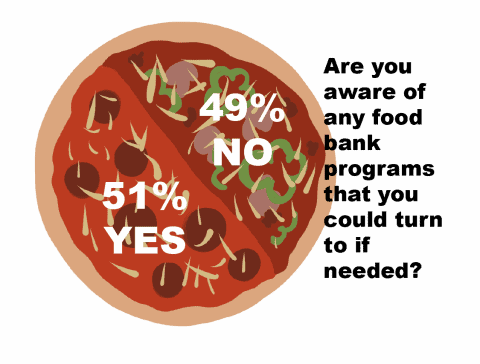

A recent study conducted at the U of S and published in December 2017 found that 39.5 per cent of participants experience food insecurity to some degree. To get some of our own answers, the Sheaf ran a poll, which was open to students and advertised on PAWS, that aimed to get an overview of what students are experiencing when it comes to food. This poll ran for approximately one week, consisted of 10 questions and received over 200 responses.

Fifty percent of the participants in the Sheaf poll admitted to skipping a meal out of financial concerns. Half of participants also stated that they have no knowledge of any programs that can help them acquire food in tough times.

The amount of food students can access in a day also varies from person to person. Forty-one per cent of poll participants get three meals a day and 47 per cent get two, while nine per cent replied that they have only one meal or less on average. A small minority of three per cent indicated that they have four or more meals a day.

To discuss food security on campus in more detail, the Sheaf spoke with Caitlin Olauson, who completed her master’s degree at the U of S in community health and epidemiology and worked on the aforementioned study as part of her master’s thesis. In the interview, Olauson broke down the demographics of the students in her survey who indicated that they experience food insecurity.

“From the results, we saw that some characteristics of certain demographics had a higher association with being food insecure — for example, international students, students who are parents, Indigenous students and students who used government student loans as their primary income,” Olauson said.

Olauson states that the study met its projected response rate of 30 per cent among those who received the survey over email, which was sent to around a quarter of the student body. Olauson also shares her opinion on the results.

“I think the main take-home for me is that the food-insecurity piece is one piece of a greater conversation that needs to be had around student poverty,” Olauson said. “There is a ton of food waste, and food access isn’t just financial, … like if you are a vegetarian or if you have religious restrictions. Can you find the foods that are appropriate to you?”

Barriers such as financial stability and geographic location — like living on campus with few grocery stores nearby — also exist and can be hard to see, because they are outside what is typically considered when discussing food security.

The Sheaf poll found that a majority of students are in a good geographical location to access food quickly. Twenty-eight per cent of poll respondents only need five minutes to get to a grocery store, and another 35 per cent fall within a range of six- to 10-minute travel times.

The third biggest grouping was the 20 per cent who have a 11- to 15-minute travel time to a grocer, and an added 17 per cent fell somewhere between 16 to 30 minutes or more. This final statistic is particularly important to consider, as students often have little time in their days to spend on anything outside of school, and the distance to a grocery store can impact access to food as well as create stress.

Rachel Engler-Stringer, an associate professor in community health and epidemiology at the U of S, supervised Olauson while she completed her master’s program. Engler-Stringer explains that student food security is important, because education can have a great impact on job prospects, and that food access while one is a student can be a barrier to education for some.

“Whether it’s university or trade school or technical school of some sort, having a post-secondary education is more or less a requirement in order to get these jobs in our society, and if we are going to live in a society that is going to require that, then we need to think very carefully about the accessibility of [education],” Engler-Stringer said.

She notes that the two primary costs that students face are housing and tuition. The Sheaf poll also found that participants spend a significant portion of their budgets on food. Indeed, 36 per cent responded that they spend 21 to 40 per cent of their budget on food, and the second largest group, containing 31 per cent of participants, replied that 41 to 60 per cent of their budget goes towards meals.

To combat these costs, Engler-Stringer recommends that the U of S lower on-campus housing costs, which she notes are currently priced at 90 per cent of market value. She also points to rent control as an off-campus solution. As for tuition, Engler-Stringer states that a tuition freeze should be seriously considered and campaigned for in Saskatchewan.

Patti McDougall, vice-provost teaching and learning at the U of S, weighs in on solutions that students can turn to right now in order to alleviate any food insecurity they may be experiencing. She mentions foremost the U of S Students’ Union Food Centre, describing it as possibly one of the best of its kind.

“This year, Culinary Services has teamed up with the USSU Food Centre by providing 50 single-meal cards per month… These meal cards are being handed out through the USSU Food Centre. The university also gives out over 250 grocery cards each year, when students find themselves in a financial crisis,” McDougall said, in an email to the Sheaf.

Despite the excellent services offered by the Food Centre, the Sheaf survey found that a substantial number of participants feel embarrassed about accessing food-bank services.

Indeed, although 36 participants said they feel no embarrassment regarding the idea of accessing food banks, 100 students responded that they would be embarrassed to use a food bank, but that they would still go through with it. However, 88 students stated that the embarrassment would keep them away from the food bank entirely.

McDougall notes that another avenue, which students can pursue in times of food insecurity, is crisis-aid loans and grants.

“Last year, the university provided almost a quarter of a million dollars in crisis-aid loans and crisis-aid grants. We expect this amount of crisis aid to grow bigger in [2018], and the university is ready to support that growing need,” McDougall said.

On the food production side, the Sheaf spoke to Grant Wood, assistant professor in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources. With regards to food insecurity and access options for students, Wood highlights Chep Good Food Inc. projects — such as the Backyard Gardening Program, which links gardeners without space to garden with those who have backyards. As an alternative, Wood also suggests that students can make arrangements through other means.

On the food production side, the Sheaf spoke to Grant Wood, assistant professor in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources. With regards to food insecurity and access options for students, Wood highlights Chep Good Food Inc. projects — such as the Backyard Gardening Program, which links gardeners without space to garden with those who have backyards. As an alternative, Wood also suggests that students can make arrangements through other means.

“A slightly different approach to the [Backyard Gardening Program] is for students to put an ad on Kijiji, or other social media, saying they are wanting to grow some of their own food but desperately need a space to do so. Hopefully, someone who is not using their backyard will allow the student to garden in it,” Wood said, in an email to the Sheaf.

Wood also recommends the U of S Horticulture Club, which can be a resource for students looking to learn how to grow their own food.

Food security is a complex issue that will undoubtedly require us to persevere and consult many perspectives before we can solve the problem. Although the U of S does offer services to help students experiencing food insecurity, both Olauson’s study and the Sheaf’s poll demonstrate that the problem is far from over.

—

Jack Thompson / Sports + Health Editor

Graphics: Lesia Karalash

Leave a Reply