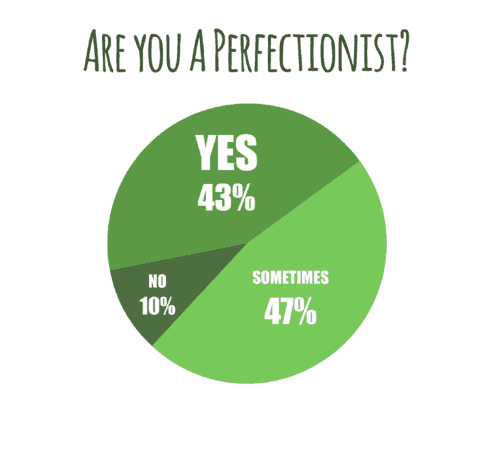

In a poll conducted through thesheaf.com in September and October of 2016, 350 students reported on whether or not they deal with perfectionism. Almost half — 47 per cent — said that they do, while only 10 per cent answered no, with the rest replying “sometimes.”

If we take these numbers and draw a conclusion about the student body on a larger scale, almost half of all students at the University of Saskatchewan dealwith or have dealt with feeling the pressure to be perfect.

Nicole Tainish is one such student. Tainish is the student health outreach co-ordinator for Peer Health Mentors on campus and a fourth-year political studies student. For her, transitioning out of high school contributed to perfectionistic tendencies.

“I think it kind of started in my last year of high school; getting ready to come to university just kind of ramped it up. I came to Saskatoon not really knowing anyone … so then I spent a lot of time just working on my school work and trying to perfect it and get the perfect grade, which is really hard in university to get a high 90 [per cent],” Tainish said.

Tainish is not alone, and academics are one of the highest areas in which students feel this strain. Wanting to achieve perfectionism in university is almost natural — most students hope to do well and excel in their area, be it academics, athletics or any other discipline.

Perfectionism is typically defined as a self-imposition of very high standards, combined with an all-or-nothing approach used to continually assess one’s behaviour and personal performance in a number of areas. These high standards are usually accompanied by an unrealistic expectations of what can personally be accomplished.

Failure to accomplish a personal set of expectations can lead to depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and even eating disorders, among other outcomes. For Tainish, perfectionism led her to burn out early in the term.

“I think for the most part, just trying to be perfect and striving for that 100 per cent leads to burn-out really quickly,” she said. “I know that everyone in university gets burnt out at some point, but I noticed that I would get burnt out around the first week of October, which is not healthy at all.”

According to Sara Liebman, an advisor with Disability Student Services at the U of S with a background in mental health and clinical psychology, striving for perfection is something that can affect an individual both inside and outside the classroom.

“[It can affect] interactions with others, in planning events — parties, dinners, group events, etc. — and in even preparing what their dress code is for each day. When it comes to studies, it’s difficult to hand assignments in on time, since these are rarely considered as ‘finished’ and always need more work,” Liebman said, in an email to the Sheaf.

In some cases, perfectionism can cause students to procrastinate. In the Sheaf’s online poll, 44 per cent of respondents agreed that perfectionism causes them to  procrastinate, while 36 per cent said it does sometimes and 20 per cent said it does not.

procrastinate, while 36 per cent said it does sometimes and 20 per cent said it does not.

“The perfectionistic tendencies might even prevent a student from handing in their exam on time in extreme cases, even if they’ve completed it way before the end,” Liebman said. “These students oftentimes tend to spend a good deal of time left in the exam by going over their answers repeatedly and again, in extreme cases, will correct right answers, risking that the ‘correction’ is actually wrong.”

Tainish experienced procrastination in her school work as well, due to the fear of getting something wrong.

“It definitely contributed to my anxiety, which kind of played together,” she said. “I got to a point where I didn’t want to go to my classes, and I didn’t want to even do anything because I knew I couldn’t be perfect.”

Beyond academics, there are many other situations in which perfectionism can cause stress to students. The Sheaf’s online poll asked participants for the top three areas in which they worry about perfectionism and the answers varied, showing that people feel pressure from the desire to be perfect in a wide range of everyday activities.

Among the top answers, school and academics ranked the highest at 31 per cent, followed by personal skills and achievements at 28 per cent. Personal appearance came in at 16 per cent, followed by relationships and partners at nine per cent and finances at eight per cent.

Despite the variety of areas, academics still comes out on top. For Tainish, the university environment contributes, in some way, to this higher percentage.

“I think university definitely contributed to [my perfectionism]. I think there’s a lot of pressure from parents and other students, and I’m a really competitive person. I don’t really play sports anymore, so I think I channelled all of my competitiveness from sports into academics,” she said.

At the same time, the university environment helped Tainish to realize that perfection is impossible to achieve.

“I think [university] definitely fueled my perfectionism, but also made me realize after a few years that you can’t be perfect all the time. Seventy-eight [per cent] is still a really good grade in university.

I think there’s a stigma that everybody needs a high 90 to be valued, but that’s not really the case. You have to look at your work and the university’s grading system — I think setting more realistic goals and realizing that real life is a whole lot different than university,” Tainish said.

The university environment may not contribute to everyone’s experience of perfectionism — only 29 per cent of poll respondents feel that their perfectionism has worsened since entering university, while 19 per cent feel that it has improved.

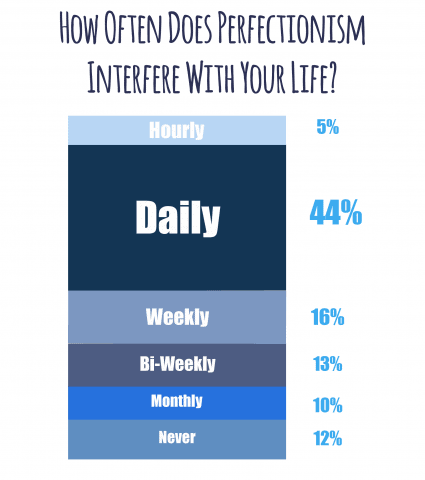

However, 44 per cent of students reported that their perfectionism affects them on a daily basis, but only 12 per cent said they had ever sought a doctor or counsellor’s help.

Liebman notes the importance of knowing when to get help and how to help yourself.

“If the level of perfectionism is so intense and anxiety-provoking that functioning on a daily basis becomes frequently impaired, like, ‘I cannot go to class this morning or go anywhere today because my hair is a wreck or my eyes are too puffy, etc.,’ then it’s time to get some professional help. Student Health [at the U of S] would probably be a good starting point, depending on the intensity of the condition. Student Counselling is also a good resource on campus.

“If, however, the perfectionism is manageable, then certainly finding ways to ‘take the edge off,’ by relaxing with friends who appreciate us and getting onto a fitness routine to help us stop thinking or ruminating about how our assignment is not up to par or not good enough yet to hand in, is a good idea. Using substances to relax or to ‘take the edge off’ is not an effective strategy,” Liebman said.

She adds that striving for success in the first place is often not the true problem.

“Having high standards for ourselves is not wrong, but severely criticizing and belittling ourselves repeatedly for not meeting these standards is definitely not the best plan of action,” she said.

After a friend approached Tainish out of concern, she went to see a doctor and got some medication. Since then, she has learned how to minimize the impact perfectionism has on her life.

“Usually, I find my idea of perfection is getting every reading done sometimes. If I feel like I need to get them all done by this certain time, I will instead just pick one and do a really good job of that homework piece that night and just set a timer on my phone. So I might spend 20 minutes working on an assignment or reading, and then I’ll set a 10 minute break and I’ll go for a walk or go watch a sports thing on TV for a bit. So I’m not sitting there for eight hours trying to get them perfect.”

Tainish also offers some important advice for students who may be dealing with a similar issue.

“I think that it’s really important to talk to your professors. That’s something I didn’t really do until my third year. It’s good to ask how you can do things differently if you don’t like a grade on an assignment. I think the hard thing for people who do deal with perfectionism is, if you get a grade back that you don’t like, you just kind of shut down and then don’t want to do anything else. But if you just wait 24 hours and then go talk to your professor about what you can do differently, I think it can be super helpful,” she said.

There are also resources available on campus for students who feel they need help. For example, Peer Health Mentors offers student-to-student support and information on time management, dealing with stress, proper nutrition and much more. Student Health Services and Student Counselling are also available for support, as well as DSS.

The struggle to be perfect in university does not have to go unaddressed or unnoticed. While everyone deals with some level of stress, the most important thing is to make sure it’s not taking over your life, and if it is, to seek whatever help you need.

“Perfectionism often leads to really high stress levels, and a little bit of stress or anxiety can be normal,” Tainish said. “It’s perfectly normal to feel stressed about a midterm or final or an assignment. But when it starts controlling your life, then that’s when it’s important to seek help.”

—

Naomi Zurevinski / Editor-in-Chief

Infographics: Lesia Karalash / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply