The psychology of language studies how we acquire, represent, understand, encode and produce both visual and auditory language — including both its dysfunction and biological, cultural and historical foundations. The field goes by many different names, but modern scholars prefer the “psychology of language” to pithier terms like “psycholinguistics” and “neurolinguistics.”

PSY 256: The Psychology of Language is a class well worth taking, especially at the University of Saskatchewan. Ron Borowsky, professor of cognitive neuroscience and faculty member in psychology, has been teaching the course for over 20 years — while actively researching language at the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab on campus.

Although his area of expertise is cognitive neuroscience, Borowsky notes that the psychology of language is interdisciplinary — likening language to a puzzle piece that links a variety of disciplines together, beyond the scope of psychology alone.

“Language is kind of a hub — and there are different cultural, biological [and] sociological interests with it,” Borowsky said. “And, to me, that’s the definition of a really rich interdisciplinary field.”

Borowsky stresses that there are many different paths that lead to language — from writers and researchers to neurologists and speech therapists to anthropologists and philosophers, almost anyone can study the psychology of language. He notes that his own students have taken various approaches — from computational modelling and mathematics to neurobiology and neurophysiology to language disorders and speech pathology.

Borowsky explains that passion and the pursuit of knowledge is really all that matters.

“It’s like lifelong learning, as an academic, and the passion and the motivation of what you’re interested in is what should drive it… Students should really select training experiences and courses that reflect their passion… The liberal arts and sciences are a wonderful way to pursue knowledge,” Borowsky said.

Borowsky is also an associate member in neurosurgery with the College of Medicine, and he notes that the CNL has been fortunate enough to explore multiple facets of cognitive neuropsychology, including helping neurosurgical patients in Saskatchewan.

“If we can do something that helps patients — great! That’s great, because not a lot of labs, in general, have that ability to work both on basic research and curiosity-driven, advanced knowledge — as well as translate [that] to help society,” Borowsky said.

He adds that the CNL works with six neurosurgeons, mapping patient brain function before resection procedures.

“We are regularly asked to help with neurosurgery patients,” Borowsky said. “Before a neurosurgeon decides where to cut, we test the patients and provide a map of where the various cognitive and language-based processes are that might be nearby, so that they have a good guide as to what areas they should avoid… They of course want to avoid any eloquent cortex.”

Because the psychology of language is such a multifaceted field, there are many rich areas to mine. Some of the most interesting subdisciplines of language psychology include figurative language and metaphor, communication in animals, the psychology of emoticons and emoji, and language as social justice — promoting equality, inclusivity, accessibility and literacy.

Figurative language pervades our spoken conversations, clarifying even the most difficult concepts through poetic description. Figurative devices like metaphor are needed to bring clarity out of obscurity, convey novel concepts and promote both memory and understanding. A metaphor compares two things by equating them as functionally, topically or thematically the same to convey information in simple but evocative ways.

Borowsky stresses the expressive potential of figurative language — characterizing metaphor as an essential communication device that facilitates the transfer of knowledge by attempting to foster connection and understanding between people.

“[Metaphors] connect our semantic [systems], … [or] worldly knowledge, … to someone else’s,” Borowsky said. “And, if I find that referring to something through metaphor is a potential bridge … then indeed, I think that metaphors serve [as] an incredible link between different individuals.”

Metaphors are especially useful if the speaker doesn’t have the vocabulary to articulate a concept or if the vocabulary doesn’t exist yet, a concept known as inexpressibility. In this way, metaphors act as bridges to the unknown.

The definition of language presents another unknown. Throughout recorded history, scholars have asked themselves how language should be defined. Is it a distinctly human skillset, or do other types of animal communication count? Moreover, if we teach signs and symbols to animals, like chimps and dolphins, does that count as language?

Language is often judged on its generative capacity and linguistic productivity — which centre on the idea that a limited number of components, such as letters and words, can be used to create virtually an infinite number of new words and sentences. Using these principles, some language theorists, such as Noam Chomsky, would say that animal communication isn’t language.

“There are some folks, like Chomsky, who have fairly set constraints or rules about what language is or isn’t, and I know when he’s asked a question like this, he refers to things like — how generative is that communication system?” Borowsky said. “So Chomsky, when asked, ‘Does this chimpanzee’s ability to use sign language constitute language?’ … Chomsky’s clear about that — he doesn’t think [so].”

However, Borowsky elaborates that even Chomsky acknowledges some forms of animal communication as comparable to human language.

“[Chomsky] would actually say that the waggle of the honeybee is the closest, because it’s infinitely generative … so his definition is very interesting. I don’t think I agree with it. I have to admit, I have a different definition than Chomsky when it comes to what constitutes language,” Borowsky said.

Borowsky clarifies that his personal definition of language is much broader.

“I would define language more as effective communication between any organisms,” Borowsky said. “I think that allows for that sense that we might have of a communicative bond with our pets… There are situations where I feel like we shouldn’t be ‘specist’ about it — if that’s a word — the idea that only humans can have this advanced language ability.”

Much like our understanding of language, modern usage has also evolved — especially since the development of the internet and social media. From emoticons to emoji to stickers, these new methods of symbolic communication pervade our electronic dialogues — but it turns out that the smiley face is more than just frivolous fun.

Cutting-edge research, presented at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society’s conference in San Francisco on March 26, indicates that emoji carry out complicated linguistic functions succinctly — such as conveying irony and sarcasm. Scientists discovered the same electrical pattern in millennial brains whether sarcasm is indicated by spoken intonation or a winking emoji.

These symbols can also be used to show empathy and emotion in written text, standing in for the facial expressions and tone of voice present in face-to-face discussions. A study of the emoji used on Instagram, for example, indicates that six of the top 10 emoji are facial expressions.

Borowsky agrees with the sentiment that emoji and emoticons convey emotional tone, highlighting that they do so efficiently.

“I think the richness of emoticons in communication — and the fact that we spend so much time on our devices and we communicate with each other so much more frequently now through those means than perhaps we did in the past — [shows that] we should consider … how [an emoji] might actually help convey someone’s emotion … [in a way] that cannot be achieved quite so efficiently with words,” Borowsky said.

He further notes that emoticons and emoji are potential fodder for neurocognitive research.

“As we’re rapidly communicating with our thumbs on these devices, being able to pull up an image or two that help relay the sentiment is very much an important part of language and worthy of study,” Borowsky said. “We’ve certainly been studying picture processing and word processing for quite some time.”

Moreover, Borowsky says that cognitive neuroscientists are always finding new ways to study language.

“Language itself is evolving, too,” Borowsky said. “As [with] emoticons, we are finding new things to study all the time, and they sometimes relate to things that we’re very familiar with, like basic picture processing.”

Borowsky further notes that he is hopeful about the direction in which language is evolving.

“I feel that we can expect a world that can only get better as a function of better communication,” Borowsky said. “A lot of the difficulties we have in our world are problems with communication — and sometimes, we draw lines that seem rather artificial to me, where we aren’t co-operating with each other as a planet as well as we could — and again, I have hope that it’s through language and communication that it [becomes] a better world.”

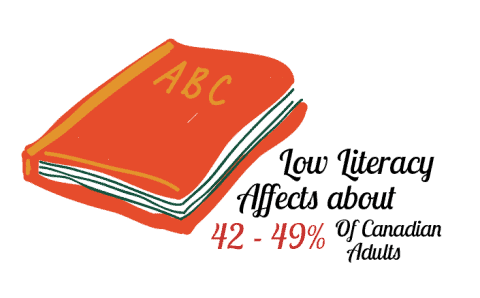

One way to build a better world is to strive for increased inclusivity and accessibility in our language. For example, the singular they dates back to the 16th century, and while the word has long been used in forms like “everyone wants to feed healthy food to their pets,” recent usage also reflects a more modern understanding of gender.

Borowsky says he supports the singular they, explaining that having a gender-neutral personal pronoun is necessary.

“It was about avoiding sexist language — instead of saying he or she, say they — and I applaud that… It does serve the purpose of getting us away from traditional gender-tied references, and in today’s world, that’s maybe even more important… [Academics are] responsible to not go down a path that could lead to what appears to be a gender bias or a particular acceptance of a dichotomy,” Borowsky said.

Just like the singular they, the psychology of language is going strong, and Borowsky encourages students to consider pursuing a career in the field.

“I think having a passion for communication and language and the representation of knowledge [is] very stimulating… I enjoy this work, because we’re still just beginning to figure out how language operates in the mind and the brain, and actually, the body as well…” Borowsky said. “And to me, it means this is going to be a very rich field of study for a very long time.”

If you want to learn more about the psychology of language, take PSY 256 from Borowsky and visit homepage.usask.ca/~rwb471/ for more information about the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab.

—

Amanda Slinger / Copy Editor

Graphics and info graphics: Lesia Karalash / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply