GREG REESE / RORY MACLEAN

Arts Writers

The year is 1968. You’re sitting down having a cold stubby and a fat joint at your good friend Dale’s place. The shag carpet feels nice and fuzzy under your bare feet, and clouds of incense smoke drift languidly about you. Dale brings out a record and sets it on the turntable. He flashes you the cover: Switched-On Bach.

“Bach! God damn it, Dale. I ain’t no friggin’ a-wrist-toe-crat!”

“Hold on, Smithy. Give ‘er a chance.”

He puts the record on and turns the volume knob to 11: Beeediddlydiddlybeeebeeebeeeediddlydiddlydiddly.

“Wow, man. This is great!”

“What did you say? I can’t hear you.”

“What?”

“What!?”

The sounds overwhelm you. Dale lights the joint. The age of the synthesizer has begun.

Actually, you and Dale were a little late to the sonic revolution. Jean-Jacques Perry and Gershon Kingsley had already been making synthesizer recordings for Vanguard Records and, in 1966, they released The In Sounds From Way Out.

The Monkees, too, had already released an album featuring Moog synthesizer: Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones. But don’t feel too bad; none of this diminishes the massive influence of Switched-On Bach.

“Most of the early recordings were soundtracks or TV themes or weird promotional recordings of covers,” said Brennan Hart, the artist behind the IDM (intelligent dance music) project Knar. “They were trying to show that synthesizers could be used to make music, because back then a synthesizer took up the space of a small car.”

Though invented at the beginning of the 20th century, it wasn’t until the mid ’60s that synthesizers became a staple of pop music.

The Moog synthesizer, invented in 1934 by Robert Moog, was the first to be used in popular music. The main advantage of the Moog was its portability.

“The company Moog started to make cheaper, simpler and more portable keyboards that were geared more for the needs of musicians rather than production teams who needed spaceship sound effects. After that they seemed to be everywhere,” said Hart.

The progressive rock giants Emerson, Lake and Palmer broke ground by using the Moog and the Hammond Organ live in concert in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Their shows included elaborate, handcrafted costumes, canon fire, virtuoso musicianship and, well, drugs — lots and lots of drugs.

Meanwhile, the Beach Boys had discovered a synthesizer of a different sort, a much earlier invention: the Theremin. By moving one’s hand closer or further away from an antenna, a person is able to modulate the sound of the Theremin. You can hear the Theremin in the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.”

At the same time, over in Germany, Edgar Froese began the band Tangerine Dream. Tangerine Dream was the first group to use exclusively synthesizers. With synthesizers, Tangerine Dream created ambient and psychedelic soundscapes. They were a formative group in the creation of a new genre dubbed “Krautrock” by the British press. Tangerine Dream were sonic explorers, using the range of moods that the synthesizer could create.

After its acceptance into mainstream music, the synthesizer morphed into numerous forms. In the ’80s, numerous break dance records used completely electronic effects.

The vocoder made it possible to transform the sound of the human voice, proving, once again, that not all technological advancements are good technological advancements, the disastrous effects of which can be heard on Neil Young’s Trans.

Despite becoming an indelible part of popular culture, analog synthesizers had many downsides; the capabilities were very limited when compared to more recent digital models.

Up until about 1977, most analog synthesizers were only capable of producing one or two notes at a time, due to the complexity of generating even a single note.

The advent of microprocessors changed everything, providing more memory to save sounds that could be played simultaneously, increasing the sonic potential.

Slowly but surely, digital synthesizers began replacing the first wave of analog synthesizers.

“Digital synths were at first pretty clumsy to create sound on, much like an old computer,” said Hart. “Instead of having a bunch of knobs and sliders they would have a little screen on them like an alarm clock.”

But they improved. They were less expensive to manufacture and, in the minds of most, the sound quality had surpassed analog. Eventually the range of effects the synthesizer could create was broadened.

“You can adjust all sorts of things,” said Steve Reed, the synth master extraordinaire from Maybe Smith and Shooting Guns. “I love twisting cut-off knobs on filters. I like running it all through an effects change”¦. I can work with reverb and delay and just get lost. Like playing a pinball machine where everything is out of hand, you have to get your hands in there. It’s like a logic puzzle, like Sudoku.”

But even with the range of possibilities that digital synthesizers bring, some mourn the absence of analog synthesizer sounds. Though Reed does not count himself among them, he admits that there is certain appeal in analog synthesizers.

“My friend Steve Caston always says, ”˜Analog just means broken.’ I think that’s great. What really gives them character is how they deteriorate. There is warmth in the individual character. It’s aging. It’s like when a guitar is made of really good wood.

“It got to a certain point with the fidelity of polyphonic synthesizers that it was harder and harder to tell if it was analog or a simulation of analog. When it has that CD quality, it’s impossible to make a case that you can hear the difference between analog and digital except the dirt and grit of analog — which is fantastic.”

Brennan Hart compared the movement back to analog synthesizers to the resurgence of vinyl over compact discs — essentially a matter of subtle aesthetic preference.

“Because of this slowly growing market, some companies, like Moog, have started designing and selling new analog keyboards,” said Hart.

Clearly the synthesizer has never left pop music since its emergence in the mid ’60s. Hart cited a number of bands that continue the tradition of synth-heavy music.

“I like Plone, Boards of Canada, Holy Fuck, trs-80, Download, Ladytron, ohgr, Sheep on Drugs, Ratatat, Takako Minekawa, the Tuss, the Rentals and Modeslektor.”

Back in the 1970s when crunchy digital grooves were just a dream, newly emerging music departments in universities across Canada were hopping onto the analog wave, including the University of Saskatchewan.

“It was new and people were still trying to figure it out, right? So we thought we better get one,” said Troy Linsley, administrative officer at the U of S music department.

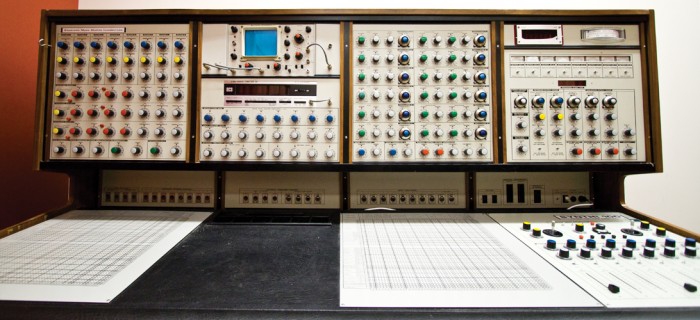

In 1974, the U of S purchased a made-to-order Synthi 100 from Electronic Music Studios of London. The Synthi 100 is a great beast of the analog era — five feet high and seven feet wide with two keyboards, a three-track sequencer and two patchbays with push pin circuitry and a whole assortment of knobs and sliders. Only about 30 units were ever produced, one of which was used by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to generate sound effects for television shows like Dr. Who and radio programs like The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

“But it doesn’t make a really complex sound,” Linsley said. “When I was a student here we used it. This technology, it’s like, there’s no point anymore. If you have, for example, a reel-to-reel recorder, it’s great, it still does recording, but why would you? We record direct to CD now. I’m not saying it’s outlived its life, but it’s not a practical tool either. If students were to get really comfortable using it, well they can only use it right here.”

Linsley has looked into selling the unit, and at one point was directed to a group of potential buyers in California, but no one was interested. So it sits in a rehearsal room of the music department along with other outdated instruments — an analog graveyard.

Linsley points out another synth nearby sitting behind glass, the Putney, also made by Electronic Music Studios of London.

The Putney basically has all the capabilities of the Synthi 100, but is portable.

“The Putney, however, does not work. If we plugged it in we would start a fire.”

So here they sit: cool, retro, impractical.

“We’re going to keep it because it looks cool, but there’s no point to it. What are we going to use it for? I don’t know. All of this used to be in a room where no one could see it. At least here people can see it. We can’t get rid of it — yet anyway.”

– –

photo: Robby Davis

Leave a Reply