A raccoon sat, lazily eating a pear. He squinted up at us with vacant eyes from atop a half-open garbage bin. We laughed at his silly face. The word “Weed” was spray painted in white across the brick wall behind the cute rodent. We double-checked the sign behind us to make sure we were not mistaken as to our whereabouts; it simply repeated itself: “bpNichol Lane.”

“Really, ‘Lane’?” I said. “It’s more of a shitty back alley.”

My girlfriend took my hand in sympathy. We had walked a long way, through some bitter winds, only to find ourselves on the University of Toronto campus in a decrepit, non-descript back way. It was getting dark.

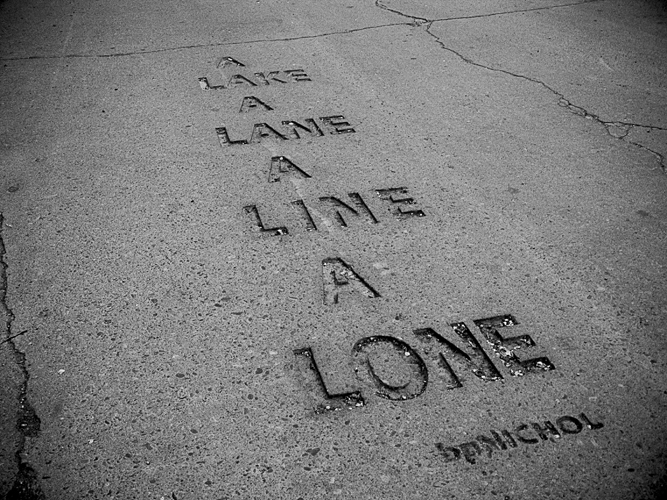

I was under the impression that the famous post-modern Canadian poet bpNichol had etched a concrete poem — in concrete! — somewhere in the lane.

Nichol, though sometimes falling into wacky experimentation, wrote fearless and witty poems that engaged the function of words and fonts and the acts of reading and comprehension at a fundamental level. He is also well known for writing episodes of The Raccoons* and Fraggle Rock. Furthermore, Coach House Books (formerly Coach House Press), one of Canada’s most legendary publishers of poetry, was said to be located somewhere nearby.

The Nichol poem we sought featured two important lines: “A / Lake.”

– –

– –

I had read that the staff at Coach House Books routinely watered the concrete grooves of the letters in “A / Lake.” It was fantastic and bizarre to think that poetry was somewhere enshrined in proper respect — how bizarre and how painstaking to keep watering a few insignificant words, day in, day out, and thereby bring into contact the abstract and the physical. Sure, it would be absolutely monotonous for the poor guy who had to water the letters, but it would be through this small act that a living work of art would be maintained for the poetry seeker or the naive back alley wanderer. I wanted to see it.

Now that we had found the place, there was a terrible and undeniable disconnection between my imagined visions and the all-too-real bpNichol Lane. We walked past a parking lot and few more garage doors. Some tinfoil swept past us and down the so-called “lane.” I was losing heart by the time we saw a few letters further down the pavement.

As we sauntered towards the impressions in the cement, we discovered that what we had initially thought was another garage was, in fact, the missing publishing house. There could be no mistake. The building had small windows lined with poetry, even a bpNichol collection. A printing press was actually running inside, cuchunk-cuchunking, and spitting out the same page endlessly — jet-black ink pressed on long, white paper. In a small way, the sight of the active machinery mellowed my disappointment at the unceremonious alleyway.

Now the poem lay directly in front of us. We walked around it so that we could read it right-side up: “A / Lake / A / Lane / A / Line / A / Lone.” My heart sank. No one had watered “A / Lake.” The rumour was a sham, or the task long abandoned.

“What the hell is wrong with these lazy bastards?” I said. “These literary cock suckers! The University of Toronto is a load of shit.”

My girlfriend, calmly observing my distress, took out a bottle of water from her purse and started watering it. I stopped her because I was thirsty — and defeated. We left.

I drank too much beer that night, and bad gas brought bad dreams. Nichol’s lines came racing back. But this time I came upon the poem from the other direction; the first two words I read made up the last line of the poem: “A / Lone.” The line felt heavy. There was a solemn weight to the statement. The back alley was cold and desolate, maybe more so than during the crummy visit earlier that day. A ghostly image of bpNichol appeared to me. He stood looking down at his newly shaped words; the impression was still wet in the cement. Clearly he was alone, just like the poem said: “A / Lone.”

Mechanically, the poem began to explicate itself for me. Like in so many dreams, I had no personal agency. The images and ideas were gifts.

First, it struck me that the initial three lines were descriptive facts: “A / Lake” was supposed to be just that (that is, if the sons of bitches at Coach House Press hadn’t given up so God damn easily on watering it!); “A / Lane” was the location of the poem (though, it really was more of a dirty alley); “A / Line” spoke to the line of poetry and maybe the alignment of the phrases, or the arbitrary way we read from left to right and top to bottom in lines. But “A / Lone” was heavier, and it wouldn’t let up in the dream, or even upon waking.

Nichol’s poem had taken its time to grow on me, but slowly new readings began to pile up. On top of it all, I began to understand that the experience of visiting this one poem was symbolic of much more. It was a decent metaphor for poetry.

Hidden away, and off the beaten path, the poem lies, ambivalent to the reader. Many people have inadvertently trampled over its lines, and, of those who have paused to observe it, many think it’s too obscure or just plain insignificant to bother with it.

Then there are those like me who pompously think that it deserves greater recognition. We would coerce uninterested children into reading it. Eventually, the poem — the cornucopia of sacred knowledge — would be read on every street corner, breathing the public air.

Yet, my experience with Nichol proved the opposite. The ingloriously placed poem now spoke clearly, saying, “Poetry is currently in its proper and correct place. In fact, it is because it is hidden away and forgotten by most that it gains a secret potency.”

I think bpNichol had intended for his poem to be hidden and alone in that alley, just as the poet is alone in society. Without even the slightest possibility for corruption by wealth, fame or power, the poet can write with humility and honesty (and experiment to their heart’s delight). Bums and hippies are welcome; feminists, bartenders, janitors, schoolteachers and even professors can be poets. And the readers — if they find it at all — will find it unsuspectingly. One by one, they will fall prey to its subtle influence. Late at night, in old age or youth, in drunkenness or sobriety, they will find it — not on the altar but in the dumpster.

–

*Correction: The article originally stated that bpNichol wrote episodes of Care Bears and Fraggle Rock. In fact, it was episodes of The Raccoons and Fraggle Rock.

– –

photo: Flickr / DuChamp

Leave a Reply