Exploring the significance of poppies for Remembrance Day

It’s that time of year again when poppies are pinned over the heart, on the left side, in an act of respect and remembrance for our fallen soldiers. In all Remembrance Day events, the red flower is universally featured. Though performances, speakers and procedures may differ, this delicate floral iconography remains a common denominator.

For over a hundred years, poppies have been inextricably linked to war memorials in Canada and many other commonwealth countries. The story of the formation of this link is one of finding hope in times of tragedy.

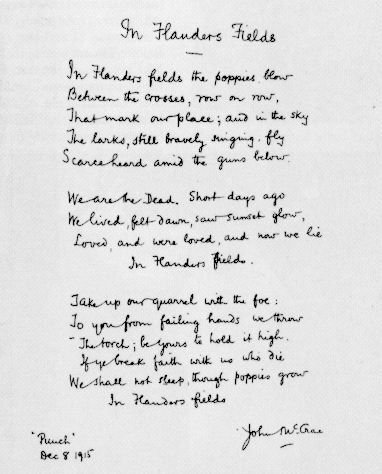

After John McCrae, who served as a gunner and brigade surgeon during the first world war, watched his close friend Lt. Alexis Hannum Helmer die on the battlefield, he penned the poem, In Flanders Fields. Some retellings of this tale say he wrote his defining literary work inside a dressing station and others say it was on an ambulance step. Regardless of the murky origins, this poem is the reason why we wear poppies on Remembrance Day – but this hasn’t always been the case.

McCrae tried to get his poem published in The Spectator, a popular political magazine based in London, but it was rejected. He was eventually able to get it published in an unassuming section of a British satire magazine without his name attributed. Shortly after its debut in December of 1915, the poem captured the heart of the public, eventually having its place cemented in history and annual Remembrance Day proceedings. Citing it as an inspiration, Madame Anna Guérin of France was the one who came up with the idea for the Remembrance Poppy. She created poppies out of fabric to raise money for the charity she founded that worked to help France rebuild after the First World War.

Before the lyrical prose, the poppy was just a poppy. The flower grew in abundance on the battlefields of Flanders during the First World War, after the dormant seeds were fertilized by the blood of the fallen. McCrae’s poem had only popularized its inherent association with the somber reminder of the costs of war.

It’s easy to get caught up in the romantic heroism of it all – to fight and die for one’s country so that those at home will live to see a peaceful tomorrow. But what is important for us all to remember is that poetry only comes after the war. The glory that we see portrayed on screens or in old battle footage are seldom felt by the ones that lived through conflict – gun in hand or not.

No longer human are the individuals that make it back from the battlefield. They come back shells of who they once were, struggling to distance themselves from the senseless blood-shed and terror, while at the same time balancing on the podium that friends and family had crafted for their living legend to stand upon.

And let us not forget the innocents left to pick up the pieces after the soldiers have come and gone. The shopkeeper sweeping up bullet casings and shards of broken glass. The young boy watching his peers play a makeshift game of soccer, his phantom leg kicking on reflex each time someone’s foot makes contact with the can. The child that will never be able to wake her mother, even as her tears fill an ocean.

There are many events across Saskatoon where you can pay your respects. Some notable ones include Beading with Auntie here on campus at the Gordon Oakes Red Bear Student Center on November 6th from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m., where you’ll be able to make poppies using Indigenous beading techniques, the 96th annual Saskatoon Remembrance on November 11th at SaskTel Center and on the same day, an annual commemorative Remembrance Day concert by the Saskatoon Chamber Singers.

Leave a Reply