This year’s Global Village event presented by the International Student and Study Abroad Centre included a panel of refugee women who shared their experiences of gender inequality in education. The annual week-long celebration of cultural diversity featured online performances, socializing and roundtable discussions presented by various campus groups.

The panel was hosted by the University of Saskatchewan local committee of the World University Service of Canada, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving educational opportunities for youth, women and refugees.

Students of the WUSC Student Refugee Program, an initiative that sponsors refugee students and combines resettlement with opportunities for higher education, highlighted the importance of supporting girls’ education in crisis-affected countries.

Achan Kiir, a Sudanese refugee and one of the panellists, described her experience of her family supporting her education despite obvious barriers, such as not being able to afford school supplies and a lack of educational infrastructure.

“My greatest support system and one of the reasons I’m successful today is my mom,” Kiir said, who highlighted the importance of promoting education among refugee children.

“Why is it most important to … give girls a chance to better their education? Because when we are done, we are empowered, we have our jobs, we can give back to society.”

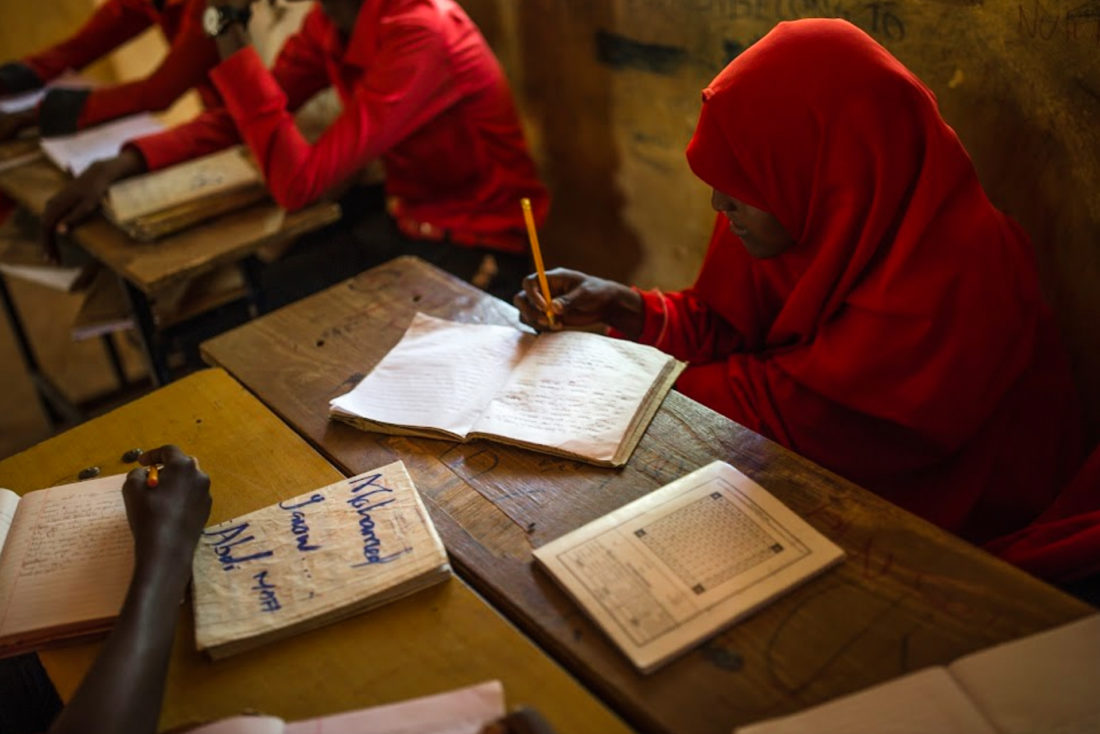

To better education, one educational fund from WUSC saw the enrollment rate for girls in Kenyan schools increase by 15 per cent. But Nyapal Duop, the second speaker in the panel, said that with scarce resources and overcrowded classrooms, many students are unable to get a proper education.

“In a class, you would get over 300 students and they really don’t get to learn anything … so a lot of them would prefer just to stay home rather than go to school,” Doup said concerning her experience as a refugee who migrated to Kenya as a child.

According to Doup, the lack of education infrastructure in refugee camps is not the only barrier to girls’ education. The panellist then went on to explain how gender roles often limit education opportunities among girls since their families don’t see a need for them to attend school.

“ [Society] takes the girl child for granted in the sense that they don’t deserve to go to school. They only have to grow up and, once they’re of age, [get] married off … and that’s it.”

Doup said that she recalled her family conforming to these gender norms, as they supported her brothers’ educations, but not hers. The only way Doup could attend school was in secret.

“I used to sneak into school every morning with my brothers, and one time [my uncle] caught me when we were going to school. But yet, [my education] had just started there,” Doup said.

Panellists agreed that deconstructing internalized gender differences is what provided them with the opportunity to earn an education.

“My inspirational quote is, ‘What our minds can do, a woman can do better’… It’s only gender where people are different, but the brain is pretty much the same,” Doup said.

As a result of her education, Doup feels that she has the power to improve the conditions of her home country.

“I’m going to make a change back at home. The peace and security of my country depend on me,” Doup said.

“Once I take care of myself, I can take care of my family. I can extend that to my country and I can extend that to the entire world and change the world.”

—

Annie Liu | Staff Writer

Photo: World University Service of Canada (WUSC-EUMC) via Facebook

Leave a Reply