On Nov. 19, Wanuskewin Heritage Park announced the discovery of four petroglyphs — a prehistoric art form where images are carved into rocks.

The discovery was made in August of 2020 by Ernie Walker, PhD, the chief archaeologist and co-founder of Wanuskewin, but was not publicized until more recently because the park had to follow protocol and consult with Elders first.

Walker, who is also a professor in the department of archaeology and anthropology at the University of Saskatchewan, made the discovery with the help of graduate students Honey Constant, Tara Janzenr and Katie Willie.

Coincidentally, the four petroglyphs were found near the same bison jump that Walker named Newo Asiniak in 1982, which translates to “four stones” in Cree.

“I can’t remember why I named it Newo Asiniak,” Walker said during the Nov. 19 press conference. “I had no idea those boulders were there.”

Wanuskewin has been the focus of much archaeological research over recent decades. It is home to many artifacts and geographic features, including bison jumps — a cliff formation used to hunt and kill bison — that tell the story of life in the Opimihaw Creek Valley. But until now, Walker says that story was incomplete.

“We have bison jumps, we have teepee rings, we have deeply buried campsites, we have a medicine wheel,” Walker said. “What was missing is something that we would refer to as rock art.”

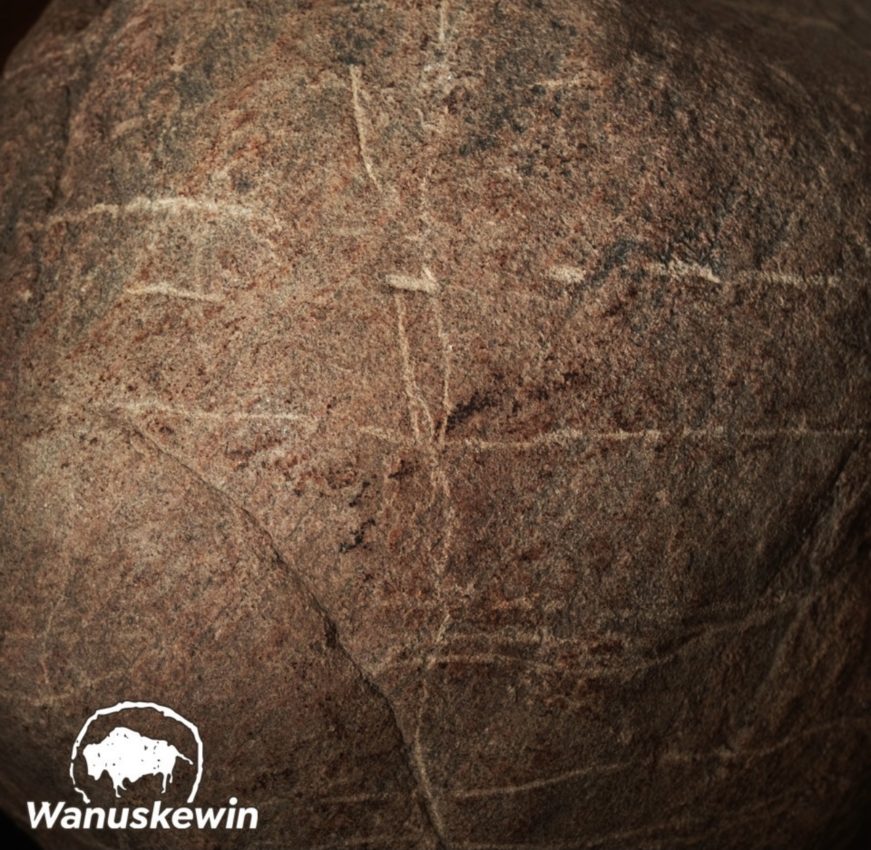

The discovery includes a 225-kilogram ribstone — a petroglyph that resembles the ribs of an animal — which is currently on display at the park’s interpretive centre.

Even more fascinating than the discovery itself is how it was made, says Walker.

In 2019, bison were reintroduced to the park as part of a $40-million revitalization project that included conservation efforts to increase bison numbers across North America.

“Since the bison have come back to Wanuskewin, they’ve changed everything.” Walker said. “Those bison that we brought back did something. You could use the term miraculous, but they did something unusual.”

Walker explained that the bison had stripped most of the vegetation in the bison paddock where the artifacts were found and were, therefore, responsible for partially uncovering the submerged ribstone.

In the following days, three more petroglyphs and a stone knife were discovered nearby.

Constant told the Sheaf that, as an Indigenous woman, the discovery is important in dispelling harmful myths — particularly that Indigenous peoples were responsible for the downfall of the bison.

“What these rocks tell us is the spiritual connection people had to bison,” Constant said. “These rocks highlight our relationships with them and how much we honoured them.”

While it is not possible to determine the exact age of the artifacts, Walker estimates that they are anywhere between 300 and 1,800 years old.

According to Walker, the discovery is so remarkable it’s worthy of designating the park as a UNESCO World Heritage Site — a protected landmark with cultural, historical or scientific significance.

“It’s clear to me that [Wanuskewin] wants and needs to be a great Canadian park… This place wants and needs to be a World Heritage Site.”

Wanuskewin was named to Canada’s tentative list in 2017 and is awaiting official designation, which Constant says would go a long way in supporting reconciliation efforts.

“Archaeology is a great way of taking back my heritage and sharing it with all of us who lost it,” Constant said. “To put it on a world stage can do so much good in terms of correcting misconceptions and telling the truth.”

A recently signed memorandum of understanding between the U of S and Wanuskewin Heritage Park will further strengthen the park’s bid for UNESCO heritage status, says Darlene Brander, CEO of Wanuskewin.

Currently, there are 20 World Heritage Sites in Canada. However, none of them are located in Saskatchewan.

“This [discovery] is what destiny looks like and this day is a big part of our journey,” Walker said.

—

Jakob Philipchuk | Staff Writer

Photos: @wanuskewin via Instagram

Leave a Reply