Eugenics is the practice of selecting “desirable” traits to “improve” the human species while “breeding out” traits that are deemed “undesirable.” The idea should seem disturbing to us in 2019, yet it appears that the spirit of eugenics is alive and well.

The headlines of the past year have been full of recent disturbing sterilization practices, new technologies and even hot takes that are all deeply rooted in the eugenics practices of old.

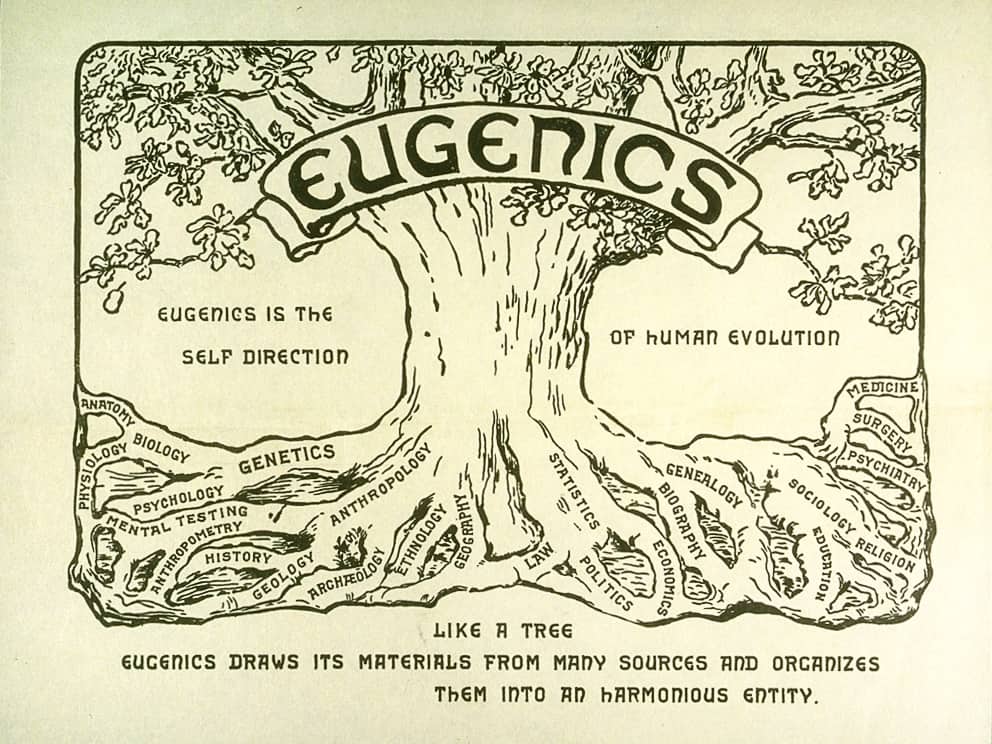

Eugenics was a burgeoning movement in the early 20th century as science and technology was beginning to flourish. Much like the debunked practice of phrenology — a once herald technique of reading the bumps on a person’s skull to understand a person’s mind — eugenics is rooted in dubious premises and rife with racism, sexism and ableism.

The practice of eugenics has a long sordid history. The word itself is of Greek origin meaning “good birth,” and is an idea first brought forth by Plato around 378 BCE. It is something that went dormant until it was brought into the light of the late 19th century by the intellectual Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin.

After reading his cousin’s book, On the Origin of Species, Galton was convinced that the human race could be improved upon by selective breeding. He wrote a book about eugenics which became a great success in scientific circles. The movement gained momentum in Europe and was welcomed with great enthusiasm in Canada and the United States.

American lawyer Madison Grant expanded on Galton’s theory with his book The Passing of the Great Race. The book was fairly influential in the 1920s and was read by many including Adolf Hitler. Hitler even wrote to Grant to applaud his work and is quoted as calling the book “my Bible.”

At the time, mental illness and “criminality” were thought to be a heritable trait. The movement turned its focus to people who were institutionalized or diagnosed with a mental illness or intellectual disabilities. The goal was simple: stop these “undesirable” traits from being passed on to another generation. Soon the practice of sterilization became common, a procedure performed either without consent or with coercion.

Eugenic societies were founded across Europe and North America as the movement flourished, but with the rise of Nazi Germany’s race hygiene practices, the support of eugenics began to falter. Eugenic societies and publications changed their tarnished names but the practice never stopped — it only went underground.

In April 2019, an alarming number of Indigenous women came forward with their experiences of forced sterilization — a practice that, shockingly, was legally enacted in some provinces during the height of the eugenics movement. The laws were eventually “phased out” in the early 1970s but the practice persisted. The most recent was reportedly performed in Saskatchewan in 2018.

In the 1930s, the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta passed legislation that allowed for involuntary sterilization of people deemed to be “unfit,” but no eugenics laws were passed in Saskatchewan.

Yet our insidious relationship with eugenics continues on into the 21st century. It is a movement deeply rooted in our western history. Legendary premiere of Saskatchewan and father of medicare, Tommy Douglas, was a eugenicist.

His research focused on “The problem of subnormal family” and looked at population control. But it’s been suggested that a trip to Nazi Germany in the 1930s influenced Douglas to distance himself from practice and his decision to not implement an “official” eugenics program.

The forced sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada echoes to a disturbing history of pseudoscience based on racism. It may be the most stark incarnation of the liveliness of the movement.

Another disturbing iteration was a dating app from Harvard researcher George Church. The app is designed to prevent matches between people with so-called “bad genes” with the ultimate goal to stop inherited genetic disorders from being passed down to their offspring.

While dating apps like Tinder, Bumble or Grindr are looking to set you up with a hook-up or perhaps a partner, this app is one that sets you up to mate — making it more of a breeding app than anything else. Its very premise is problematic.

George Church, the creator of this app, adamantly denies the vocal comparisons to the days of yore eugenics programs. However, it should be noted that Church’s lab received funding from the now infamous Jeffery Epstein, who was interested in eugenics like philosophy and spoke of his plans to “seed the human race” with his own DNA.

In December 2019, The New York Times published an article that analyzed the IQ of Ashkenazi Jews. Bret Stephens wrote his pieces on the heritable genius of Jewish persons of Ashkenazi descent, hinging his premise on a controversial 2005 paper from a researcher that has been celebrated by white supremacist groups.

Days later, NYT removed the reference to the 2005 paper and left an editor’s note about the decision to do so. This article is an example of race science, the idea that there are inherent and measurable differences between races that make one superior to another. It is an idea which ultimately lends itself to practices like eugenics.

This past year has proven that eugenics is not a skeleton we have shoved in our historical closet, but it’s a living and breathing entity that is still flourishing in the shadows of today.

—

Erin Matthews/ Opinions Editor

Photo: Flickr | Peter K. Levy

Leave a Reply