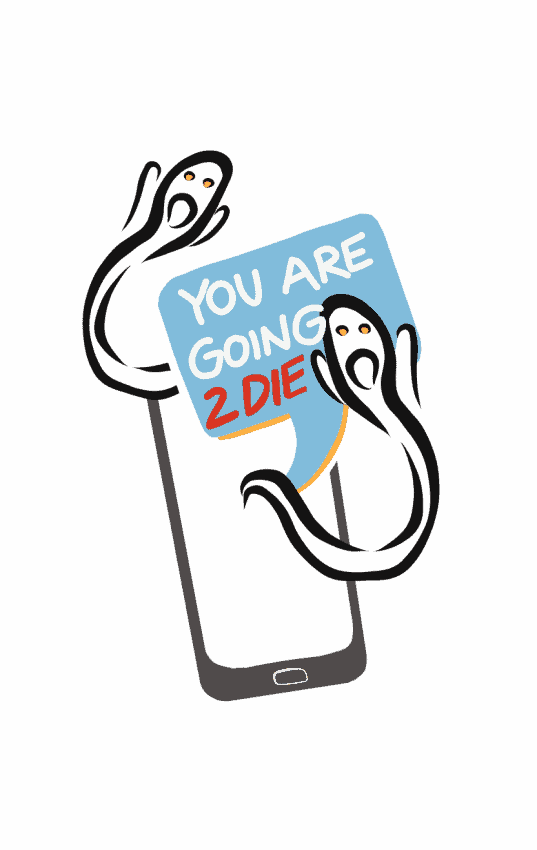

Horror and science fiction narratives have been creeping around for hundreds of years. From Frankenstein to The Fly, we have been haunted by stories of monsters, technology gone wrong, death and violence.

What makes these narratives so compelling and terrifying is the way that many of them blur between reality and fantasy. These stories become a manifestation of our collective anxieties — our fears about ourselves and the world around us. The descent into darkness fills us with unease because we know that this darkness is closer to us than we would like to admit.

Shirley Jackson wrote about haunted houses and the woman that occupied one — what better metaphor for a woman’s psyche in 1960 than a house full of ghosts? Many novels and movies in the horror genre use supernatural elements as a metaphor for our anxieties.

This kind of storytelling is easily translated to any kind of medium.

Limetown was a podcast that aired all the way back in 2015. It followed investigative journalist Lia Haddock as she tracked down the truth behind the disappearance of 300 people from a research facility nearly a decade earlier.

You must remember Limetown, one of the biggest news stories in the early 2000s. The 911 call from inside the isolated community that mobilized military and media action to the locked gates of the company town nestled in the hills of Tennessee.

There was a three-day standoff between authorities and the town’s security team that prevented the entry of any outside personnel. Eventually, the gates were opened and, to everyone’s horror, Limetown was empty.

You remember it, right?

Well, it’s ok if you don’t because this investigative podcast is a manufactured reality. But it does a good job at blurring the lines of real-life and make-believe — taking narrative elements from some major catastrophic events like Roanoke, Chernobyl, Jonestown and Waco.

Unfortunately, the unique storytelling approach of the original podcast is tarnished by a strange incarnation being aired on the new Facebook Watch platform — a dystopian nightmare in itself.

This “life imitating art” approach is common to horror and sci-fi. In fact, it’s what makes the best stories the most terrifying.

It was Oct. 30, 1938 — radios across America buzzed with breaking news reports of an alien invasion. In reality, it was Orson Welles’ radio play of the H.G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds.

Even though Welles and the Mercury Theatre were introduced at the beginning of the play, the style of the broadcast apparently caused some panic and confusion.

The beginning of the play presents “news bulletins” describing strange events occurring around the country. It is not hard to see how people believed that this could really be happening if they tuned into the show while it was already in progress.

Following the broadcast, there were reports of outrage over the misleading nature of the performance. Despite the literal out-of-this-world content, people were allegedly frightened and convinced of its authenticity. However, this tale of mass hysteria may even be a myth of its own making.

But what is it about these stories that get to us? Horror and science fiction explore the deepest reaches of our minds and pull out our greatest fears and anxieties — the masked man watching us from our backyard. A house full of secrets. A devastating pandemic. A town full of people vanishing without a trace.

Our fears manifest before us in film, print or audio and we can’t help but look and listen to these stories because they are a part of us.

This may be the reason why people either love the genre or hate the genre. It’s a hard look at the darkest part of ourselves. It makes sense why many people would choose to look away.

—

Erin Matthews/ Opinions Editor

Graphic: Ana Cristina Camacho/ News Editor

Leave a Reply