One Canadian academic high on the global list of self-citing is a chairperson of research at the University of Saskatchewan.

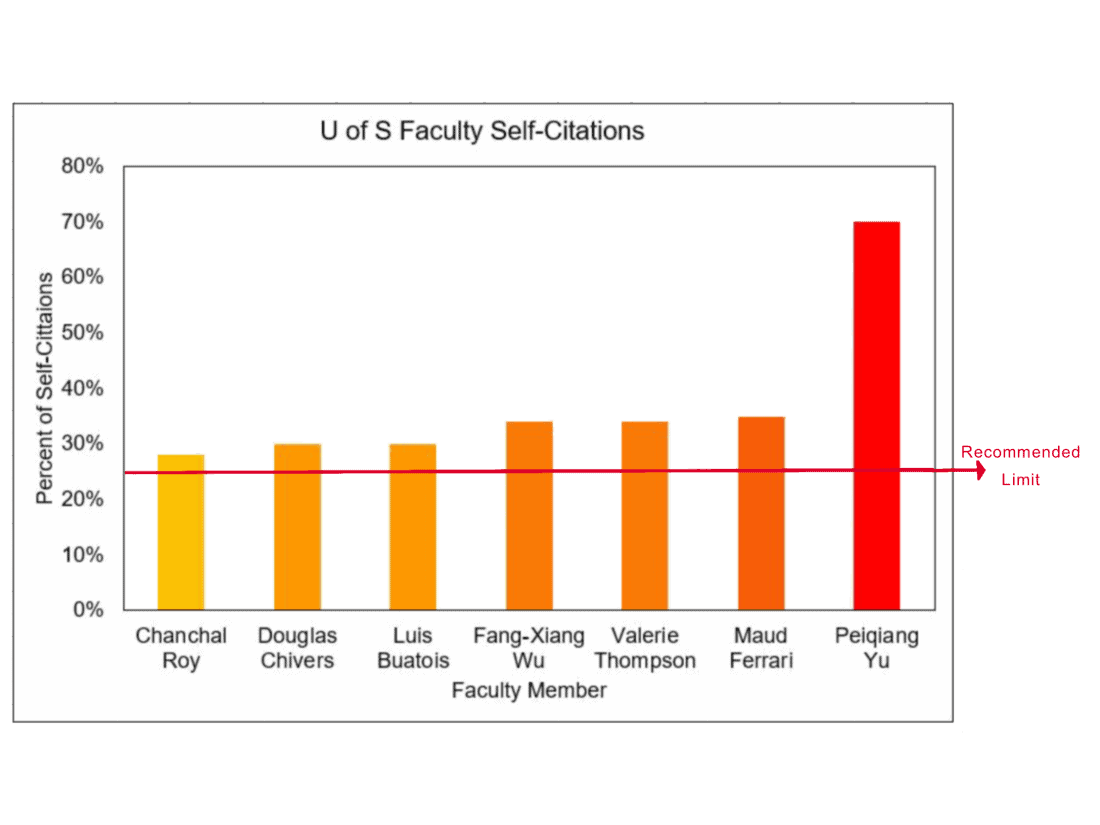

Peiqiang Yu is the chair in Feed Research and Development for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture Strategic Research Program, and is recorded to have self-cited 70 per cent of his work.

According to a study published by Nature, researchers might be worthy of scrutiny if more than 25 per cent of their citations are self-cited. Because the university currently has no policies to deter selfcitation, Yu is in no violation of citation manipulation.

Yu is one of the 59 U of S faculty members included in the study on citations. The Sheaf was unable to reach Yu for a comment during his sabbatical leave. There are six other U of S faculty who are above the 25 per cent limit for selfcitations, ranging from 25 to 35 per cent.

Andrew Potter, the U of S interim associate vice-president of research, says that the study in Nature “caught [them] off guard” and that it is not something the university previously thought was a problem. The U of S has policies for academic conduct but none in particular for self-citations.

“It is not specifically mentioned in the policy, and probably because it’s not something that there’s a consensus yet that this is a problem in any way,” Potter said.

Although it is not prohibited, excessive self-citing is frowned upon by other academics because citations can impact the decisions of universities on hiring, promotions and funding for researchers around the world. Frequently citing one’s own work can lead to inflated metrics that do not accurately reflect the impact of published research.

When asked if the limit should be 25 per cent, Potter disagreed. He believes that “it is a number pulled out of a hat” because it is not justified in the study. He also says that self-citing is necessary if researchers are repeating methodologies used in a past study that need to be cited again, something more common in scientific studies.

“So I’ve published 200 and some-odd papers. Now if I have to repeat the same methods every time, it’s a waste of space in the journal so I cite my previous articles because it describes it,” Potter said.

While self-citing is not itself a policy, the university does have two policies addressing unnecessary or repetitious citing, referred to as citation farming. For now, Potter believes that there is currently no need for a policy regarding self-citation, but that it should still be discussed.

“What we need to do is have a conversation,” Potter said. “We need to have a conversation on campus, so that would involve faculty members [and] it would involve students.”

These conversations are already underway. At the Sept. 29 University Council meeting, U of S Vice-President University Relations Debra Pozega-Osburn said that increasing the university’s “research metrics,” which includes faculty’s citations, will be part of their upcoming strategy for improving the U of S’s standing in various university ranking lists.

In the question period, a council member took to the mic to question this “emphasis on citations” and wondered whether the working groups in charge of the strategy were aware of the Nature article and the dangers of extreme self-citation. The council member says that self-citation should be a consideration in talks about university rankings as it affects the U of S’s reputation.

“[One of] the top self-citer in Canada is one of our colleagues,” the council member said. “These things affect our reputation.”

—

J.C. Balicanta Narag/ Copy Editor

Graphic: Shawna Langer/ Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply