From the mighty glass and stone shadow of the Health Sciences Building to the stoic archways and gothic peaks of the Thorvaldson Building, the spirit of science is alive and well on campus today.

And while the University of Saskatchewan has always been a hub of scientific investigation, some stories of discovery and achievement have been lost — relegated to the forgotten contents of dusty boxes or the whispers of ghost stories.

The health sciences have old roots on campus, beginning in 1919 with the inception of the department of bacteriology. Over the next seven years, this department grew into the School of Medical Sciences. The school was nestled in the Header Houses, and their ghosts still stand behind the Physical Activity Complex. The Header Houses served as labs until 1937, when the school migrated once again.

Upon completion of the Medical College Building in 1949, the School of Medical Sciences moved house for the last time. It became a full college in 1952 and was renamed the College of Medicine the following year.

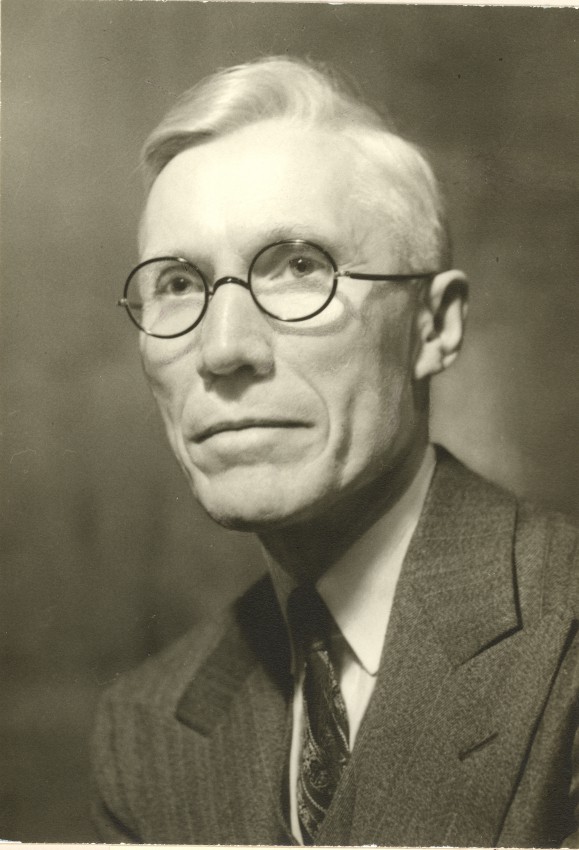

Rudolf Altschul may be a name unfamiliar to you, but he received his medical degree from the University of Prague in 1925. Travelling to Paris and Rome, he undertook training opportunities in neurology and neuropathology. During these four years of scientific discovery in Europe, Altschul investigated the brain lesions caused by carbon monoxide poisoning and made progress in histological staining techniques. He also fell in love with his soon-to-be wife, Anni, in Rome.

Returning to Prague in 1929, he began practicing as a neuropsychiatrist and continued his histological investigations for the next decade. The beginning of World War II forced Altschul and his wife to flee Prague aboard the ill-fated SS Athenia, the first Allied boat to be torpedoed by the Nazis. The couple survived the ordeal and eventually made their way to Saskatoon where Altschul joined the U of S department of anatomy first as a professor and then as the department head.

Altschul was not only a scientist but also an avid writer and storyteller — penning drafts of two novels and a handful of poems, short stories and essays. He also submitted a radio play, The Seven Pills of Wisdom, to CBC.

Altschul often referenced himself in his writings — musing about his life and experiences — such as this passage from one of his essays, found in the University Archives and Special Collections.

“Before I go ahead with my stories, may I introduce myself: physician, psychiatrist, brain anatomist, psychoanalyst; some sort of jack of all trades; also amateur in literature and art; speaking and writing in five languages, one of which is supposed to be the mother tongue although I am not quite sure which it is.”

Altschul goes on to speak of his journey to Canada after fleeing his home.

“Born in the navel of Europe in a medieval mysterious city, reborn 200 miles west of the Hebrides after a shipwreck — rescued from the waves of the ocean and sharing this kind of birth with Aphrodite, the Greek Deesse of Beauty. However, time of birth and beauty are not common to us.”

While at the U of S, Altschul’s research focused on atherosclerosis, plaque deposits caused by high levels of cholesterol that can lead to heart attacks and strokes. His discovery led to a better understanding of how niacin, vitamin B3, can be used to lower blood cholesterol. The treatment, although no longer popular, is still in use today.

The Chemistry Building — now known as the Thorvaldson Building — was the one of the last of the original Gothic Collegiate designs. It was direly needed to meet the demands of the chemistry department, which had outgrown the makeshift labs in the College Building, now named the Peter MacKinnon Building. According to University Archives and Special Collections, it was said to embody the spirit of the roaring 20s and had a placement that differed from the rest of campus.

“It faced not inward toward the Bowl and original buildings but outward to what was expected to be an expanding future.”

Thorbergur Thorvaldson may be best known as a campus ghost story with grandiose legends of his entombment and the haunting of the building that now bears his name. Thorvaldson was born in Iceland, settling in Manitoba in the late 1880s. Known as “TT,” he studied at Harvard before arriving at the U of S to become a professor of chemistry. He became head of the department in 1919, five years after he first joined the university’s staff.

His discovery of sulfate-resistant-concrete formulas saved buildings from crumbling, changing the commercial manufacturing of cement around the globe. However, either intentionally or by a mere oversight, no patent was sought for the process — meaning that Thorvaldson did not profit from his innovation.

Thorvaldson received the highest honour of Iceland when he was knighted by the Order of the Falcon. A year after his death, the Chemistry Building was renamed after the chemist.

Over the last 50 years, Thorvaldson’s legacy has been mainly contained in the old building — with the rumours of his body being entombed in the concrete block on the front steps. Contrary to this urban legend, his final resting place is a gravesite that he shares with his wife, Margaret, at Woodlawn Cemetery.

The original building housed not only the department of physics but also the now defunct botany and zoology departments. The federal government’s research departments in plant pathology and soils could also be found within the building.

Vibration-resistant walls were constructed to minimize environmental disturbances that could affect the research being conducted. There were many laboratories conducting cutting-edge research within various domains of physics — including electricity, magnetism, light and electron physics. The roots of physics run deep on the Prairies, with many innovations and complex discoveries happening right here on campus grounds.

Born in rural Saskatchewan, Sylvia Fedoruk was encouraged to pursue science by her English teacher. Upon entry into the U of S, Fedoruk was the only female enrolled in her first-year engineering and physics classes — a theme that continued for most of her career. In the 1950s, Fedoruk was the only woman in medical physics in Canada. She became a radiation physicist for the Saskatoon Cancer Clinic and eventually stepped into the role of chief medical physicist.

Her contributions to medical physics were numerous, including many new cancer treatments. Working under Harold E. Johns, she was the only woman on the four person team that created the world’s first cobalt-60 unit — an innovative radiation therapy that revolutionized oncology.

Fedoruk’s list of achievements stretches as far as the Prairie horizon, with a long record of “firsts” including first female Chancellor of the U of S, first woman on the Atomic Energy Control Board of Canada, first female trustee of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and first woman appointed as Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan.

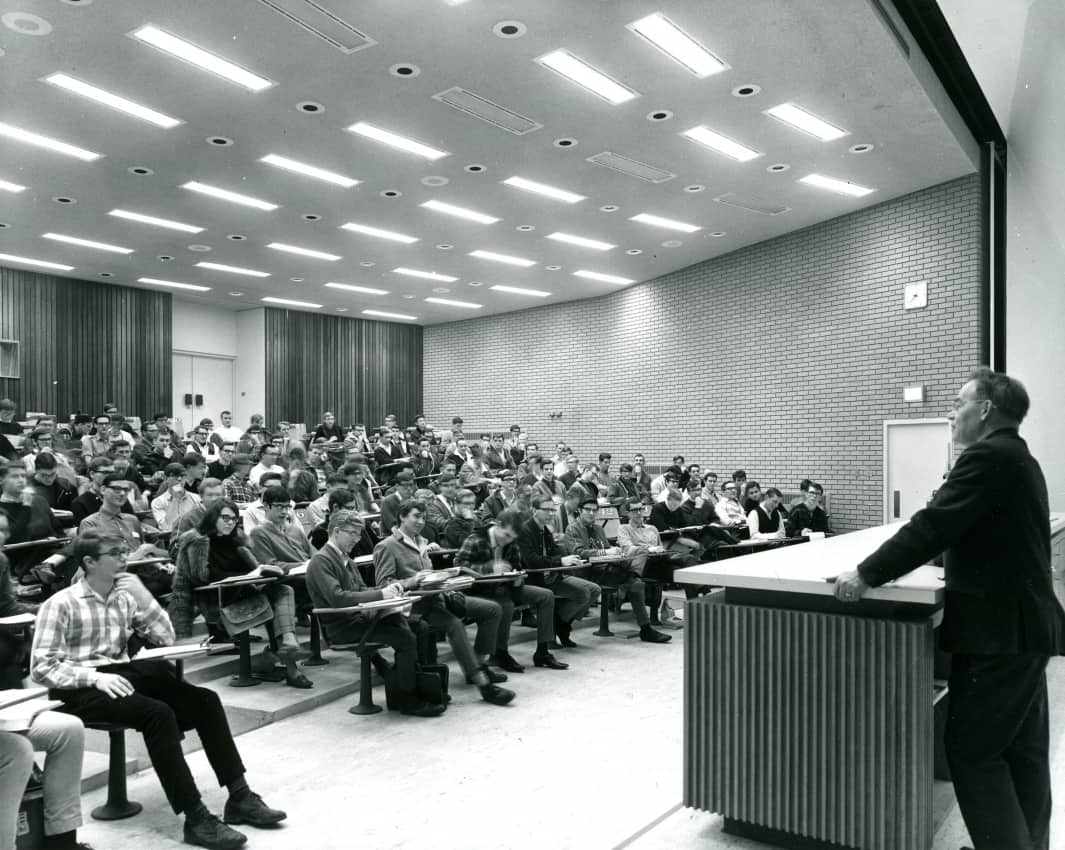

Leon Katz was a nuclear physics pioneer, and his research made waves that still resonate toda. He played a role in bringing to campus the betatron – a cyclical partical accelerator used in physics research and the treatment of oncology patients.

Katz championed the university to build a linear accelerator, which was perhaps his biggest contribution to physics on the Prairies. His rallying paid off, and in 1964, he became director of the brand new Linear Accelerator Laboratory, or LINAC, later known as the Saskatchewan Accelerator Laboratory. After 35 years of research, this lab was instrumental in ushering in the Canadian Light Source synchrotron, the first and only research facility of its kind in Canada.

After 100 years of scientific research, the U of S has many stories of science scattered across campus.

Some are more well-known than others – with legacies etched on building exteriors or plaques hung in harshly lit hallways. Yet, many stories, like that of Altschul, lie forgotten on dust-covered shelves.

Storytelling is an important aspect of science. As Jim Kozubek says in his article for Scientific American, “Science is messy, full of plot twists and competing interpretations – and the way we talk about it should reflect that truth.”

The same is true for the scientists behind this work. Science is a human activity driven by curious minds. Their lives, too, are messy, full of plot twists and just as unique as the discoveries that they have been part of.

—

Erin Matthews / Opinions Editor

Leave a Reply