There is perhaps no topic more contested than that of vaccination, despite having been in practice for more than 200 years. There is a constant drone of conflicting opinions in the media with clashes between those in favour of vaccination and of those who are opposed.

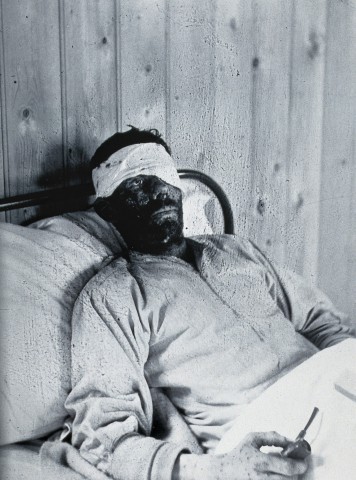

The story of vaccines goes back to 1796 when Edward Jenner, a rural physician, famously illustrated the link between cowpox — which caused a minor skin affliction in those who worked closely with cattle — and one of the most deadly illnesses of history, smallpox.

According to folk knowledge at the time, those infected with cowpox would be spared from the horrors of smallpox. Jenner was intrigued and tested this theory by modifying the practice of inoculation — which was already a common practice in Africa, China and India — with cowpox. Previously, smallpox scabs or fluid from pustules were rubbed into broken skin, which often led to a milder form of the disease and protected the individuals against a severe infection.

Jenner first used cowpox material, pushing it under the skin with a needle. He then repeated the procedure with smallpox to test the reported protective effect. The boy Jenner inoculated was spared from a smallpox infection. This was the very first vaccine trial, and it proved to be one of modern medicine’s greatest successes, eventually leading to the disease being wiped from the face of the Earth.

While the eradication of smallpox was declared in the 1980s — a feat made possible through intense vaccination campaigns — it still is estimated to have killed about 300 million people in the 20th century alone.

While smallpox is the only disease we have successfully eradicated, it is one of many vaccine-preventable illnesses. Diseases like polio, diphtheria, measles, mumps, yellow fever, chicken pox, tetanus and influenza can cause severe illness, chronic complications, and in some cases, risk of death. However, we have the ability to protect ourselves and others against them.

And yet, 2018 saw skyrocketing measles outbreaks in the United States and Europe. Measles was declared eliminated from the US back in 2000 but has returned as vaccination rates declined over the past two decades.

According to a 2018 article by CBC, Saskatchewan’s high vaccination rates are keeping children safe in the province. Numbers show that 87 per cent of preschool-aged children are up to date on their vaccinations. We need these high rates of vaccination to ensure significant herd immunity within the population.

Herd immunity refers to the protection offered to those who cannot be effectively vaccinated — such as the very young, the very old and those with compromised immune systems — by those in the population who have been immunized. If the majority of those within the population have been vaccinated, there is less chance that the microbe that causes the disease can circulate.

If the pathogens aren’t circulating, then there is less of a chance that susceptible people will get sick. When it comes to the measles, we need a 95 per cent vaccination rate to achieve herd immunity, yet rates continue to drop in many wealthy countries.

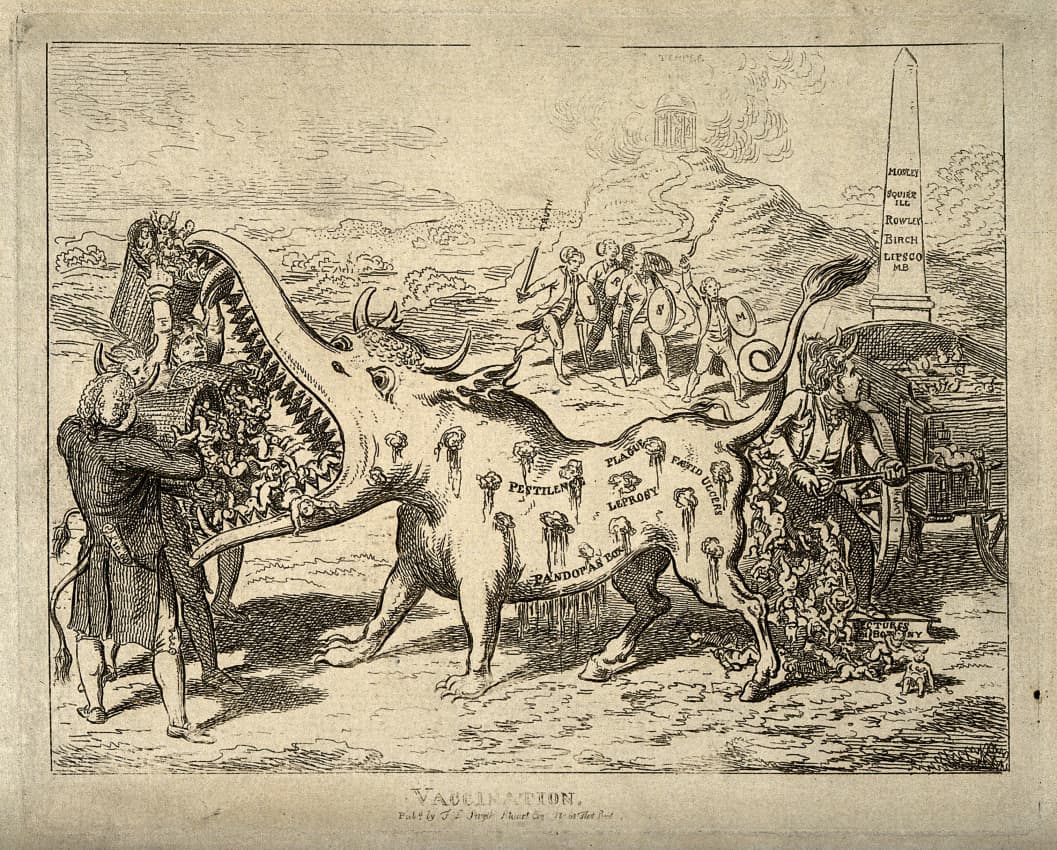

The anti-vaccine movement and its champions — known colloquially as anti-vaxxers — seemed to appear in the populace after a fraudulent paper was published 20 years ago by the now infamous Andrew Wakefield. Wakefield was stripped of his medical licence and the paper was retracted when the data was found to be falsified. Yet, Wakefield lingers to this day, spreading his message with documentaries.

But Wakefield and his followers were not the first to raise arguments against vaccination. The Anti-Vaccination League of America held its first meeting in New York in 1882 to protest smallpox vaccination campaigns. It appears that anti-vaccine attitudes have existed since the procedure’s inception and continue to hold fast as we enter into 2019.

While our vaccination rates are high, Saskatchewan is still seeing outbreaks of disease among unvaccinated children. Starting in October 2018, a whooping cough outbreak — an illness caused by pertussis bacteria — occurred in communities north of Saskatoon. Of the 24 reported cases, over half affected children under five years of age. The majority of children in this cluster were not up to date with their vaccinations.

Whooping cough can cause serious illness and respiratory distress in children and infants, leading to hospitalization in severe cases, and it isn’t the only vaccine-preventable illness we’ve seen in the province this year. The 2018-2019 influenza season has hit particularly hard with 13,796 individuals testing positive for influenza in Canada.

In Saskatchewan, influenza has killed three unvaccinated preschool-aged children since the beginning of December, according to a news story published by CBC on Jan. 9, 2019. A two-year-old girl from Wollaston Lake was the first preschool-age casualty of the virus in the province, after succumbing to respiratory complications in early December.

As far as provincial numbers go, over 1,988 people have been diagnosed with influenza this season and 14 people have been admitted to intensive-care units. The major strain at play here is the H1N1 virus — made infamous by the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic that saw an estimated 500 million people infected.

While this year’s influenza season has packed a punch, the vaccine should give you protection against the circulating viruses. By mid-December 2018, more than 280,000 doses of the vaccine had been administered in Saskatchewan.

High vaccination rates are encouraging in a province where vaccine research and development are booming. The University of Saskatchewan is home to a world-renowned vaccine-research institute called the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization – International Vaccine Centre, or VIDO-InterVac.

VIDO-InterVac has a long history on campus and was originally founded as the Veterinary Infectious Disease Organization in 1975. VIDO-InterVac has now grown to be one of the top vaccine-research institutes in the world, having expanded into human infectious diseases in 2003.

The Sheaf sat down with Dr. Sylvia van den Hurk, professor in biochemistry, microbiology and immunology at the U of S and program manager of the viral pathogenesis and vaccine development group at VIDO-InterVac. Van den Hurk is now seeing a vaccine that she and the VIDO-InterVac team developed for respiratory syncytial virus go into the first stages of clinical trials.

“It’s a very important area of research,” van den Hurk said. “Vaccines have probably saved more human lives than all other interventions combined. So it’s a particularly satisfying area to do research in, specifically if your research ends up going into a clinical trial and your vaccine candidate has a potential to make it.”

RSV is a virus that causes respiratory infections that can be extraordinarily detrimental to infants, especially those who were born premature.

“In very young infants, the virus moves down into the lung, specifically the bronchioles [or] the small airways,” van den Hurk said. “[There is] an influx of immune cells, production of mucus, [etc.], so these small bronchioles clog up, and these infants have a hard time breathing.”

Many infants need to be hospitalized and placed on ventilators to help them breathe.

Van den Hurk has been working on a vaccine for RSV for about 10 years. The vaccine van den Hurk and her team have developed is called a subunit vaccine. It consists of an antigen, a component from the RSV virus, and a series of adjuvants, substances that help to stimulate the immune system.

“Vaccine development takes decades, even once we go into a Phase I clinical trial,” van den Hurk said. “There are many people working on RSV vaccine development, and we are slowly making progress.”

Now that the vaccine is on the way to a Phase I clinical trial, it will still be up to five years before it rolls out onto the market — if the trials are successful. When asked about vaccine hesitancy, van den Hurk explains why she thinks people might shy away from vaccination.

“Wakefield really set in motion a very serious anti-vaccine movement… But the people do see a needle, and they do get an injection, and that is unpleasant,” van den Hurk said.

Along with fear and discomfort, van den Hurk notes that people may not have access to health care, may forget to keep up with their vaccination schedules or simply may not understand the severity of the diseases that vaccines prevent.

“People really, in this day and age, have never experienced the devastating effects of, for example, polio. In the 1940s and 1950s, a lot of people ended up in iron lungs due to paralysis. They have never seen the devastating effects of smallpox, plague, you name it. Yes, you hear about it, but you simply do not realize the severity any more,” van den Hurk said.

Vaccines have been one of medicine’s most valuable contributions to society, saving countless lives for hundreds of years and pushing deadly diseases to the fringes of our minds. However, in the past few years, we have seen a decline in vaccination rates leading to a resurgence of preventable illnesses that hit vulnerable people, like children, the hardest. This increased spread of disease is a side effect of under-vaccination, and as we are beginning to witness, it can quickly spin out of control.

—

Erin Matthews / Opinions Editor

Photos: Supplied / Wellcome Collection

Leave a Reply