In the hazy first days since its passing, discourses surrounding the Cannabis Act and its coinciding policies prove that all we know so far is that we know very little. Though legalization will undoubtedly divert unnecessary criminal charges and open access to the drug in a safer way, it is critical to consider the still-unknown effects.

The Cannabis Act — or Bill C-45 — passed through the senate on June 18, receiving royal assent on June 21. It was paired with Bill C-46, an amendment to the Criminal Code concerning impaired driving.

Legalization came into effect on Oct. 17, 2018, marking nearly seven years policy development — 77 per cent of federal Liberal party member-delegates voted to make legalization a party policy in January 2012. Since its inception, marijuana legislation has been the subject of both celebration and concern.

What we can expect, based on policy, is that a lot of people are going to be lost in the unknown and a lot of people are going to be overlooked. The courts are predicted to be bloated with those seeking settlement, as well. Problems that plagued the cannabis market as it previously existed will continue, including barriers to access and profiling causing prosecution.

There are the immediate standout issues, varying from province to province, yielding a patchwork of limitations. In Saskatchewan, you won’t be able to smoke up anywhere outside of private property — granted you have permission from the owner and are far away from minors.

You’ll have a hard time finding homegrown in Manitoba — the province, along with Quebec, has banned private plants — and you won’t be able to purchase a special brownie anywhere in the country any time soon if you’ve even managed to find legal bud in the days or weeks without nearby retailers.

You’ll have a hard time finding homegrown in Manitoba — the province, along with Quebec, has banned private plants — and you won’t be able to purchase a special brownie anywhere in the country any time soon if you’ve even managed to find legal bud in the days or weeks without nearby retailers.

Moreover, your trusted dealer will still be penalized if found out and could face anything from a ticket to 14 years in prison for under-the-table transactions after the legalization of cannabis.

Julie Vickaryous has been a medical cannabis patient for five years and she also works in the industry — formerly as manager of National Access Cannabis, an organization which connects patients with doctors, and now with Saskatchewan-based retailer Jimmy’s Cannabis in Martensville. Vickaryous is a cannabis chef who advocates for cannabis use both as a treatment and a potential means for harm reduction.

“Anyone who lives in Saskatchewan knows that we have drinking issues, we have drug issues plus driving issues, and I think that legalization is a way for our country to take something that’s less toxic [and make it] that kind of recreational thing,” Vickaryous said.

Vickaryous hopes that putting pot on the market will help curb high rates of alcoholism in the province and attributes her own career decisions to her belief that there is potential for the industry to thrive in Saskatchewan.

“I wanted to remain in the local scene. Saskatchewan has always been very much my home, I wanted to see the cannabis industry flourish here. We’re such an agricultural hub, and shopping local and supporting local is such a huge thing in Saskatchewan,” Vickaryous said.

Though she supports the Cannabis Act in that it marks a positive step toward greater harm reduction, she says that both her experiences in dealing with the legislation as the manager of a retail outlet and as an educated consumer has caused more than a few headaches.

“It’s just creating a more open environment for these kinds of things. I don’t think it’s being done in the best way that it could be, but I think it’s better being done than not at all,” Vickaryous said. “They wrote the rules because it sounds right to the people who know nothing about it, but [these rules are] not grounded in fact, so it’s really frustrating.”

For Vickaryous, the blurred lines between medicinal and recreational use post legalization are a dangerous grey zone, and she hopes there will be reconsiderations made sooner rather than later.

“I cannot serve anyone who appears to have used that day, and this is a huge issue for medical patients… I think what we’re going to see most is human-rights cases involving DUIs, especially with medical patients,” Vickaryous said.

Vickaryous doesn’t doubt that she’ll have to challenge a DUI charge in the near future.

“I use cannabis all day to replace all of my medications, so if I ever have the misfortune of being a woman who’s pulled over by a cop in the first place, … they’re going to swab me, and I’m going to get a DUI right away,” Vickaryous said.

Fears such as these should be no surprise, however, as limited understanding is a hallmark of the topic itself — perhaps due to certain side effects, in part, though more likely the result of decades of fear mongering, repression and racism disguised as the political War on Drugs.

Comparatively, cannabis research is lagging far behind its medicinally classed counterparts when considering its widespread use, and as a result, myths and misinformation have circulated for generations.

Canada has a long-running history of being contentious toward cannabis. When the decision was made to classify the drug as criminal in 1923, there was very little qualifying evidence to back up the so-called necessitating claims.

You might be familiar with Emily Murphy, a famed Canadian suffragette who also penned The Black Candle, published in 1922. Beginning as series of articles appearing in Macleans, allegedly intended to incite public demand for stricter drug legislation, The Black Candle attributed the use and rise in popularity of drugs such as cannabis and opium in predominantly white communities to an ambiguously defined non-white influence.

Murphy claimed that such drugs were a device intended to “bring about the downfall of the white race” and later nominated herself for a Nobel Prize. From what we can derive from the statistics in recent years, it would seem as though Murphy’s miseducated fear is most certainly working the other way.

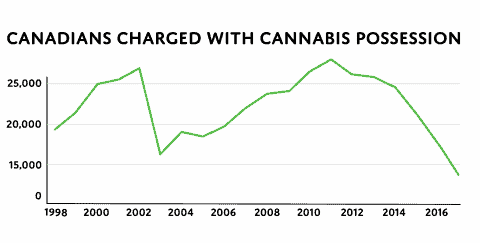

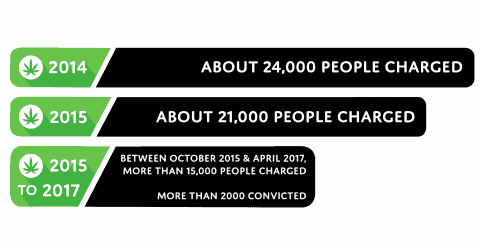

In 2014, about 24,000 people were charged with cannabis possession. That number dropped to about 21,000 in 2015, and between Oct. 2015 and April 2017, about 15,300 people were charged with cannabis possession. The number of possession charges per year has steadily decreased since as early as 2011, with numbers beginning to drop significantly in 2014.

Though the federal government is facing pressure to promptly grant amnesty to those who have been convicted of cannabis-based offences, it’s still unclear exactly to what degree this will happen.

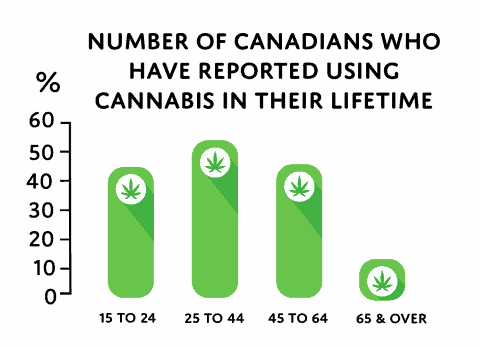

Black and Indigenous people have made up a disproportionate amount of cannabis-related charges since the Liberal party won with a majority vote on a platform to legalize the drug — and the ratios close to home are shocking. From 2015 to mid-2017, Indigenous people in Regina were nearly nine times more likely to get arrested for cannabis possession than white people despite similar rates of use across racial groups.

Furthermore, an investigation by the Toronto Star in 2017 found that Black people with no history of convictions were three times more likely to be arrested by Toronto police for possession in small amounts than white people from similar backgrounds.

According to a poll conducted by The Globe and Mail and Nanos Research, about 62 per cent of Canadians support or somewhat support pardoning those with criminal records for pot possession when legalization is in effect.

In the months following this hefty reconfiguration, it will be imperative for policy makers, industry leaders and consumers alike to consider the wider implications of what groundwork has already been laid and to continue to be critical of the rules and regulations that surround the substance.

—

Emily Migchels / Editor-in-Chief

All graphics: Jaymie Stachyruk / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply