Canada’s fifth annual Science Literacy Week wrapped up on Sept. 23 after a short, and relatively quiet, attempt at convincing the public to think about science for a small, singular moment. During this age of information, why does science seem to fall to the wayside of public knowledge?

The week is described as a celebration that aims to showcase diversity among Canadian scientists, while hopefully, getting the public excited about science in the process. There’s even a catchy hashtag: #SciLit — yet, despite strong efforts from many institutions from coast to coast to coast, Science Literacy Week seems to fall just out of the purview of the public.

This year, Saskatchewan Polytechnic held engagement booths at the Saskatoon Public Library, with two events open to the public though minimally advertised: a promotion of women in trades and technology and the more ambiguous Makerspace gadgets exhibition, featuring a build-your-own-computer kit called the Makey Makey.

Strangely, for a city that is a scientific powerhouse on the Prairies, Saskatoon appeared to lag behind Regina’s events roster — which included both coding and robotics workshops.

Science Literacy Week isn’t alone — Global Biotech Week followed behind with a wide range of events that hoped to inspire public enthusiasm, with festivities concluding on Sept. 30. Afterhours tours were held at the Canadian Light Source, and biotech trivia and Café Scientifique events were held in the basement of Winston’s pub.

Dr. Julia Boughner — an associate professor in the anatomy, physiology and pharmacology department — has been organizing Café Scientifique, a recurring event that features a structured science talk over pints of beer, for the past six years and has seen attendance and enthusiasm increase. She believes in the effectiveness of these events.

“It’s about having conversations about science with people you know,” Boughner said, when asked what the scientific community can do to change the public perception of science.

Boughner is a believer in education and starting the quest to science literacy as young as possible.

“If we can demystify science and humanize scientists to children, then hopefully, those kids grow up feeling that science is just something that we do,” Boughner said.

Science is my beat — I could churn out four science articles a week and be content for the rest of my career. With science journalism growing as a field, I doubt that I’m alone in this feeling. This interest in science is reflected in newspapers operating out of some Canadian universities, such as University of Toronto’s The Varsity and Ryerson’s aptly named Ryersonian — both of which have engaging science sections.

However, the Sheaf, like many other university news outlets, follows the standard four pillars of student journalism with our opinions, news, sports and health, and culture sections. My goal for this year is to change readers’ perceptions and show that science is welcome in the folds of this paper.

While science is trying its very best to break onto the scene with admirable attempts at attracting sustained attention, it just hasn’t quite pushed its way into the mainstream. Science is still relegated to the fringes — like the weird guy in the dark corner of the party, showing you hidden secrets from deep within his lab coat.

So, what does it mean to be science literate? Science literacy is defined simply as an understanding of scientific concepts and the processes of science. This is required for nearly everything — from personal decision making to policy making — yet, there seems to be a growing dissent toward science and a lack of understanding of some of the core concepts.

Dr. Kyle Anderson is an assistant professor in the department of biochemistry, microbiology and immunology. Anderson has been teaching at the University of Saskatchewan for nine years and recently won the 2017-18 U of S Students’ Union teaching excellence award.

Anderson says that our biggest problem, perhaps, is not with science literacy but with information literacy.

“We are drowning in information,” Anderson said. “And it’s hard for us to really understand what’s truthful.”

It appears that we, as a society, have access to more information than ever before. In the apparent post-truth, alternative-facts reality that we currently inhabit, we are becoming increasingly terrible at separating the fiction from evidence-based fact.

“Regardless of [what] your opinion is, you are able to find someone that is supportive of that,” Anderson said.

His words bring to mind recent cases, such as that of a young boy from Alberta who died after his parents attempted to treat his bacterial meningitis with naturopathic remedies.

“There are examples where people could get information that supported what they wanted to believe, even though that information was against their best interest,” Anderson said.

What is to blame for this propagation of misinformation?

To Boughner, these views appear to come in waves of both trust and mistrust, and the tides of public opinion may be generated by the political environments of the moment. It can be argued that these ebbs and flows of perception, and the lack of support from political parties, come from a lack of understanding of both the processes of science and the findings.

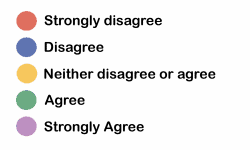

Hot topics like vaccination, genetically modified organisms and climate change all appear to cause public recoil and doubt. With the rise in popularity of alternative health websites selling questionable health remedies — such as Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop — and the increasing number of unvaccinated children in the U.S., we appear to be witnessing the public denial of evidence-based science in favour of snake oil.

This ignorance can have serious consequences. In just the first six months of 2018, there were over 41,000 cases of measles reported in Europe. This childhood illness is not harmless — in fact, it can be quite lethal. Serious nervous-system complications can occur in children, and incidences of miscarriages and stillborn births have been reported in pregnant women. It is a disease that should be a candidate for eradication, much like smallpox, and yet, it is making a roaring comeback.

This all comes back to the waning public confidence in science. Individuals just don’t trust it, and perhaps, it is an internally created public-relations problem. For decades, science has been a gentleman’s club with an ivory-tower approach. Making science accessible, it appears, is a more recent movement — one that might have come too late.

“It is hard for someone that doesn’t understand jargon to really be able to know the truth. Scientists speak in jargon… We aren’t trained to simplify things for public consumption,” Anderson said.

And that’s where science communication comes in. Despite pioneers like Carl Sagan and the perhaps more familiar Bill Nye — of Bill Nye the Science Guy fame — science communication is a relatively new exercise, which aims to promote scientific literacy by the public promotion of scientific studies. More and more scientists, graduate students and educators are engaging in outreach. The end goal is to make science more digestible and increase public awareness.

From social media to blogs to podcasts — science communicators are rolling out their soapboxes and unfolding their platforms in an effort to capture public attention and excitement. This creative-communications approach makes science more accessible to people and brings the ideas and concepts into our homes and our daily conversations.

Timothy Caulfield, health law and policy professor at the University of Alberta, has been debunking pseudo-science health claims for years, and he can now be found streaming on Netflix. Caulfield’s show, A User’s Guide to Cheating Death, takes a hands-on approach to debunking vampire facials and miracle smoothies.

The show is careful to not make fun of anyone — except perhaps Caulfield himself — and instead attempts to help people understand how science works, emphasizing the importance of evidence-based health products.

This idea was explored when I spoke with Boughner.

“Demanding evidence to support ideas and theories is hugely protective for society because it makes it harder to manipulate people,” Boughner said.“We are very emotional creatures… It also means we might have knee-jerk or intuitive responses to things. Again, having that critical-thinking, evidence-based approach to things forces us to slow down and to be objective and to make decisions that are … well informed and socially just.”

And that’s the deeper message to understanding science. Science is everywhere — it’s part of everything that we experience and everything we create. A deeper understanding of science makes us more well rounded and helps bring us together.

“Being able to understand basic-level science is going to help you figure out what you should know, what is actually important and what makes us, as a society, a little more unified,” Anderson said.

Boughner, too, echoes Anderson’s sentiments.

“Science makes us [a] kinder, more exciting and imaginative society,” Boughner said. “[It] makes us a happier society.”

Science is a human activity. It emphasises all the facets that make us who we are — our curiosity, our creativity, our thirst for knowledge and our understanding of the world around us. Science is merely a vehicle with which to explore our humanity.

—

Erin Matthews / Opinions Editor

Graphics: Jaymie Stachyruk / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply