For many University of Saskatchewan students, alcohol is a regular part of life — as is its unwelcome shadow, the dreaded hangover. We’ve all got our favorite, go-to hangover remedies, but do they really work? Is there actually a cure-all for the curse of the morning after?

Hangovers have been around for as long as humans have been drinking alcohol — which, it turns out, is a very long time. Supposedly, early humans, perhaps over 10,000 years ago, discovered alcohol in the form of fermenting fruit. It made them feel light and loopy and they decided they wanted more.

Intentional fermenting, mainly of beer and wine, was well underway by the time of the first civilizations in Mesopotamia. Ever since, separate civilizations from around the world have formed their own traditions surrounding alcohol and their own ways of taming its after-effects.

A text written in ancient Greek from roughly 1900 years ago urges those suffering from post-drinking maladies to wear a wreath around their neck made from  a shrub called Alexandrian laurel. King George IV of England was prescribed opium by his doctors as a quick fix in the 1800s. Zelda Fitzgerald, a famous 20s socialite and author, swore by a morning swim followed by another drink. A few decades later, Dean Martin took that a little further, claiming the best remedy is just to stay drunk.

a shrub called Alexandrian laurel. King George IV of England was prescribed opium by his doctors as a quick fix in the 1800s. Zelda Fitzgerald, a famous 20s socialite and author, swore by a morning swim followed by another drink. A few decades later, Dean Martin took that a little further, claiming the best remedy is just to stay drunk.

Though these remedies might sound intriguing — if frequently unhealthy — it’s unlikely that the average U of S student has access to any Alexandrian laurel, so the wisdom of past generations isn’t much use to us. Instead, the Sheaf conducted an informal poll in Place Riel to find out what students are doing to treat hangovers.

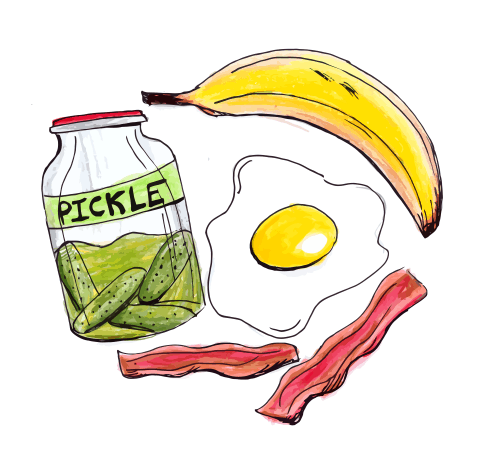

A few standard responses were repeated frequently: drinking lots of water, both before and after drinking, greasy breakfast food and various flavors of Gatorade. However, some students have their own remedies which they swear by.

Second-year arts and science student Sammy Ramsay claims to have discovered on the Internet that drinking dill pickle juice in the morning provides an ultimate cure. Kaitlin Wong, fourth-year psychiatry student, uses a combination of water and bananas. Simply sleeping it off, though, is enough for Alyssa Young, first-year arts and science student.

Clearly, there are plenty of theories out there on how to cure a hangover. The question remains, though: do any of them truly work?

Unfortunately for students who like to indulge, the answer is likely no. A 2015 study from Utrecht University in the Netherlands, in conjunction with Acadia University researchers and students, found that drinking plenty of water or eating fast food won’t change the fact that the more alcohol you drink, the more likely you are to be hungover.

Some aspects of the typical hangover — dizziness and thirst, mainly — can be attributed to alcohol’s dehydrating effect on the body. However, those dreaded feelings of nausea, weakness and general inability to function have not been scientifically tied to hydration. One current theory is that many of the undesirable morning after effects of drinking have to do with withdrawal, after the body got used to a large amount of alcohol over the previous evening.

The good news is that withdrawal symptoms will pass as your body readjusts to life without alcohol. The bad news is that there isn’t much you can do except wait it out. The idea that you can “soak up” the excess liquor in your stomach with late-night greasy carbohydrates and thereby lessen the next morning’s hangover is, sadly, wishful thinking.

So, what is a hungover student to do, faced with a day of studying or classes? Luckily, there are some solutions. Avoid more alcohol. Don’t turn to acetaminophen — brand name Tylenol — for your headache. Above all, though, just wait — time is your friend.

The culture of student alcohol use is widespread throughout history and around the world. U of S students are experiencing the same struggles with hangovers that humans have for millennia. For now, the struggle continues — until the next, best cure comes along.

—

Image: Ashley Britz

Leave a Reply