SOMA DALAI

On March 4, University of Saskatchewan interim-president Gordon Barnhart delivered a speech to an intimate crowd at Convocation Hall, showcasing a side of him not often seen nowadays: the historian.

As part of the university’s centennial commemorations of the First World War, Barnhart was invited to talk about Rev. Edmund Henry Oliver, the subject of Barnhart’s master’s thesis and one of the many professors from the university who left to fight in the “war to end all wars.”

Oliver was originally from Ontario but came to Saskatchewan at the turn of the 20th century. He died at the relatively young age of 53, but Oliver’s prolific life shaped his adopted province of Saskatchewan in numerous ways, namely through his contributions to the U of S.

Oliver was recruited to teach at the university by its first president, Walter Murray, and delivered the establishment’s first lecture on ancient history in the Drinkle Building, located in downtown Saskatoon. As one of the first buildings in the city with an elevator, Oliver began his address by joking that the building was perfectly equipped to encourage “higher learning.”

In 1912, Oliver helped found the Presbyterian Theological College, now known as St. Andrew’s College. He believed firmly in the role of a theological education, which would serve him through the battlefields of the First World War.

When war broke out in 1914, the effects on the university were immediate and devastating.

“In 1914 alone, nearly 74 per cent of the student body went to war, alongside approximately half of the faculty. In 1916, the College of Engineering didn’t offer any classes because there weren’t faculty or students here to take the classes,” said Barnhart.

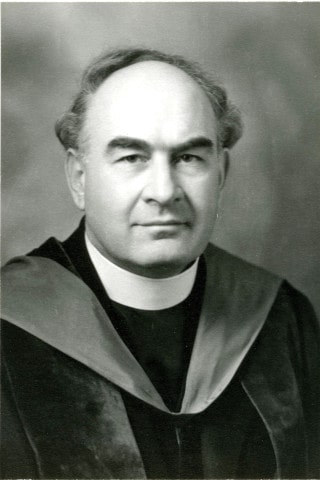

Reverand Edmund Oliver was commemorated for his contributions to the U of S during the First World War.

Oliver did not enlist until 1916, becoming an army chaplain. On the train to his first assignment to Camp Hughes, Man., Oliver wrote to his wife Rita and promised to pen a letter to her every day he was away — a promise he largely kept. Rita stored every letter, making them a treasure trove of information about his war-time experiences.

Barnhart said that Oliver left for war with several motives.

“He went there to protect the troops from two things: from alcohol — ‘demon rum’ as it was called — and he also was there to protect the soldiers from the relaxed social and sexual standards of Europe.”

Oliver frequently gave lectures to the soldiers regarding the virtues of avoiding alcohol, which was seen at that time as detrimental to the war effort, and maintaining strong moral standards. He would also help hospitalized soldiers write home, and composed letters on behalf of killed soldiers. However, Barnhart said Oliver longed to contribute more.

“He started giving lectures to the troops in England on history, literature, citizenship and all of the subjects he thought would serve these men well not only in their behaviour while at the war, but more particularly when they came home.”

Oliver also opened “reading rooms” where soldiers could come and read books on educational topics if they had time off. Oliver wrote to Murray and other university presidents requesting books for these rooms. Later on, Oliver took this idea further with 12 other instructors and began a mobile university where they would travel by bike with bags of books directly to the front. They called it the University of Vimy Ridge.

Barnhart said that Oliver felt an urgency about his mission to educate due to the enormous death tolls of the war. In a letter to his wife, Oliver wrote: “If we don’t hurry, our pupils may get shot or killed before they’re educated.”

Barnhart explained that Oliver felt education’s necessity was borne out of the belief that many of these soldiers would return to become future leaders.

“He believed that the men who survived had to be educated because they needed to be solid citizens as they re-entered Canadian society.

“The interesting thing about the work of Oliver and those 12 others and the University of Vimy Ridge — it’s interesting that those are not the things we tend to think about when we think about the First World War. You think about the heroes of the war and the number of people who died, and the trenches, and the mud and the terrible living conditions. But here were these people who were carrying books, and wanting to make sure that they had an education.”

When the war ended, Oliver was one of the lucky few who returned home. On Nov. 12, 1918, he wrote with considerable relief to Rita.

“The war is over and peace has been won. The world has been made safe for democracy, and we’ll all get home to our wives.”

—

Photo: University Archives & Special Collections