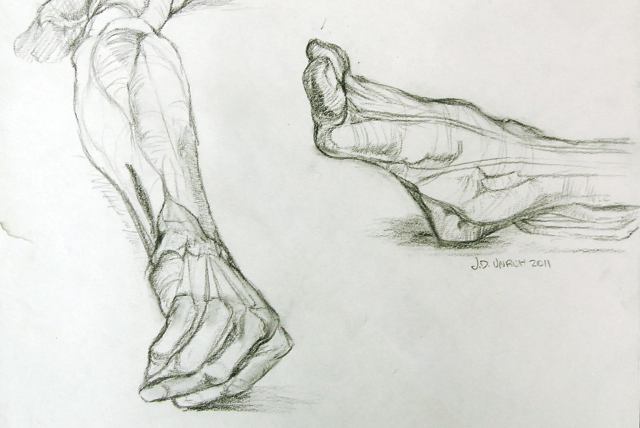

Art students use the anatomy lab to learn how the natural lines of muscles contribute to figure drawing.

The possibility of cutting the use of cadavers in anatomy labs is raising concerns that students will lose a valuable piece of their education.

The College of Medicine has begun a budgetary probe into the use of cadavers in the gross anatomy lab course by pitting the academic value against cost effectiveness. The primary concern is whether or not the lab course can be taught solely with models and virtual program.

Head of the Anatomy and Cell Biology Department Ben Rosser said the gross anatomy lab can not be replaced by models in any way.

“This is the ultimate in experiential learning. It is totally hands on and [students are] thinking while they’re doing it. You just can’t get that with working with models or virtual [programs].”

The anatomy and cell biology department runs the gross anatomy lab — the study of the body at a macroscopic level — for medicine, physiotherapy and dentistry undergraduate students and offers sessions for kinesiology students and various programs in the College of Arts and Science. Massage therapy schools also use the lab.

Rosser said there are between 600 and 700 students and medical residents that use the gross anatomy lab each year.

Since the review was made public, Rosser has been receiving emails from students, faculty members and even surgeons working at the Royal University Hospital saying that it is unbelievable that cutting the gross anatomy lab is even being considered.

An anatomy student — called “Jill” at a request to protect her privacy — said students will lose the valuable experience of working with cadavers and confronting death.

“This is a lot of people’s first time experiencing death and being presented with it,” Jill said. “You also gain that respect for the human bodies, for the cadavers and the whole process.”

The University of Saskatchewan’s body bequeathal program currently has 3,300 registered donors in the province.

When a body is received by the U of S, it is embalmed for a year before being prepared for dissections. One half of the body is used by medicine and dentistry students who dissect the thorax, abdomen, trunk and head. The following year, the limbs are prepared by lab technicians to be prosections — limbs and other parts of the body that have been pre-dissected. Kinesiology, art and art history, physiology and physical therapy undergraduates study from prosections. The body is then reassembled and a memorial service is held for the family and friends of the deceased. Students who have benefitted from the deceased’s donation are also invited.

Rosser said it means a lot to loved ones of the deceased for them to meet the students whose education was helped by the donation and knows that students also benefit from the service.

“That’s really important to the families,” Rosser said. “It is really meaningful for the students too. Although they knew it was a person that they were working with — which is crucial to their education — now they really can identify.”

The service and the burial are paid for by the university as a symbol of appreciation to the family for the donation.

Rosser said that if the College of Medicine cuts the body bequeathal program, the U of S will be the only medical school in Canada that does not use either dissections or prosections.

The University of Ottawa and Dalhousie University do not have students dissect because it is a lengthy process, however the students still learn from prosections.

The use of prosections over full dissections is more time-effective, Rosser said. However, it is not cost-effective because a cadaver is still required in order to have a prosection.

“You have to have a donated body to make a prosection from and then somebody has to make that,” Rosser said. “That’s quite labour intensive.”

If the body bequeathal program is cut, students will learn from plastic and virtual models.

Plastic models range in cost from hundreds to thousands of dollars and need to be replaced when broken. Plastinated prosections are parts of the body that have been embedded in plastic. The muscles of these models are immovable due to their hard plastic covering.

Jill said that plastinated models do not give students the experience necessary to prepare them for working with the human body.

“If you have plastinated models, you don’t get the appreciation that there is variability and that not every brain looks identical or any other part of the human body for that matter,” Jill said.

However, Rosser said that the plastic models are useful for teaching about complicated areas of the body such as the head and neck.

Virtual models range from the low-end CDs that are found in textbooks to higher end virtual dissection tables.

Rosser said that many universities do use models, but only in conjunction with the cadaver labs — adding that plastic models “are not a stand alone.”

“If there is something out there that is going to give the same experience as dissecting does and adds any cost saving additional benefits, we’d be all over it. But there isn’t,” Rosser said.

Currently, the gross anatomy labs at the U of S do not have an extra fee tacked on to them. Rosser said that some school’s anatomy labs are money generators but he is against unloading the cost onto students.

“I think it would be abominable to charge [students] money to take a laboratory course. Would biology do that? Or agriculture?” Rosser said. “I would not want to be part of that kind of institution.”

Massage therapy schools that are separate from the U of S pay a small fee when using the anatomy labs.

The review of the body bequeathal program is separate from TransformUS — a program cutting initiative to help manage the university’s projected deficit of $44.5 million — and began well before it.

Since November 2012, colleges and departments have been trimming their own programs in hopes to lessen the blow received from TransformUS.

Cutting the gross anatomy lab would save money needed to fund the program and would also eliminate the cost of the new laboratory that is planned for the B-Wing of the Health Sciences Building.

Rosser said that the plans for the new lab are complete and the next step is construction. If the use of cadavers is cut, the new laboratory will no longer be necessary.

“If you could get rid of a lab where the students had cadavers and dissections, and just have them sit at computer consoles,” Rosser said. “Yes, you would save a lot of money.”

Rosser said that cutting the gross anatomy lab would not have an immediate effect on the College of Medicine’s accreditation but it may in the future if the quality of graduates coming out of the college begins to diminish.

“There are no requirements for anatomy in accreditation,” Rosser said. “If you don’t give the students the basics, down the road they won’t be performing as well. And then it may become a problem with accreditation.”

When asked to comment on the review of the use of cadavers, Acting Dean of the College of Medicine Lou Qualtiere said the committee is in the initial stages of “doing a budgetary probe and any decision is many months away.”

—

Photo: Jodie Unruh

Leave a Reply