Twenty-three years ago, a major shift happened at the University of Saskatchewan in accepting sexual diversity.

Although provincial law stipulated that freedom of expression included sexual orientation, that did not mean that people faced no discrimination if they came out or went against the gender binary.

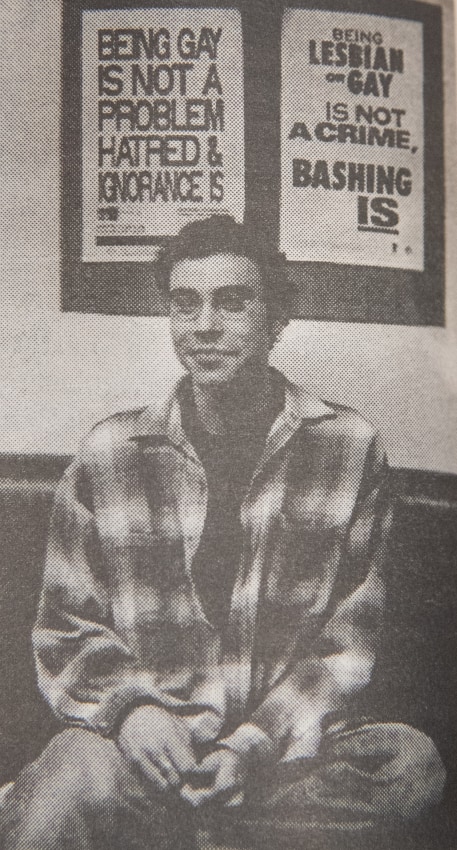

“At that time, it was a very different landscape,” said University of Saskatchewan alumnus Scott Blythe, one of the students in 1996 who pushed for the U of S Students’ Union to create a resource centre for queer students. The place that resulted from his work is what is now known as the Pride Centre

Blythe’s initiative, at the time, came out of a need to be more visible and vocal in the fight for civil rights and inclusion, something that was beyond the scoop of the already-existing gay and lesbian students’ club.

“It created visibility for queer people on campus that really hadn’t existed in any meaningful way before that,” Blythe said.

The University Students’ Council supported his proposal, and the centre opened in the Fall term of the following year. A space was carved out in the basement of Saskatchewan Hall for what was then known as the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Centre, with Blythe as the co-ordinator.

The centre at the U of S was one of the first queer student resource centres in Western Canada. Blythe fondly recalls the student council’s support for the project and how it gave him a sense of belonging that paved the way for everything that followed.

The effects were far-reaching. About five years ago, Blythe was approached by a former U of S student while walking down the street who recognized him as the former co-ordinator of the LGB Centre.

“He said, ‘You may not remember me, but you created a space for me. You had one conversation with me, but the impact of the work that you did back then has shaped everything that I’ve done moving forward,’” Blythe recalls.

“To know that I had a small part in helping shape somebody’s future was really humbling.”

At the same time, Don Cochrane, a professor in the College of Education, was pursuing the creation of a course focused solely on gender and sexual diversity in schools. Getting approval was a long process, and Cochrane recalls that a tense, three-hour faculty meeting once concluded with those in support embracing each other with hugs.

In the fall of 1997, Cochrane taught the course for the first time. From the beginning, he and the administration were thoughtful about potential issues of discrimination for the students enrolled in the course.

One issue was whether education students with the actual course title on their transcript might face difficulties getting hired as teachers, which prompted discussions about encoding the title.

Cochrane says it was the “most interesting, sensitive discussion [he] had in 30 years at the university.” The meeting concluded with the decision that they would not disguise the course title in any way. Cochrane says it was the right decision.

With these steps forward, the U of S campus was leading the way for embracing sexual and gender diversity. For 20 years Cochrane and his colleagues also deviced and hosted a “Breaking the Silence” conference for discussing ways teachers can support queer students.

While change does not happen in a vacuum, Blythe and Cochane pushed the door open for acceptance of sexual and gender diversity on campus in 1997. Those efforts have had lasting effects at the U of S.

Slowly, social attitudes progressed in the city and country-

wide. It took until 2005 for same-sex marriage to be legalized in Canada. The LGB Centre changed names and developed into the Pride Centre, still holding now an important place in the Memorial Union Building.

Blythe is proud that the Pride Centre has played a part in the conversations around sexuality in Canada.

“There’s still a need to talk about discrimination and inclusion and diversity … and all of the discussions have evolved and changed,” Blythe said. “And it’s great to know that there is a centre, that was one of the very first in Canada to exist, that is still playing a role.”

At the time of its creation, the Pride Centre was a way to fill the hole in the community left behind by the victims of the AIDS epidemic, whose deaths meant a loss of guidance for queer youth. The centre’s impact has been long lasting and on campus today it continues to impact the lives of a new generation of students.

“The thing for me is that we’ve come so far,” Blythe said. “The creation of that space at that time was really important to help the generation that I’m a part of heal from the missing elders … in ways that were really meaningful and that shaped everything that came after that.”

—

Nykole King/ Editor-in-Chief

Photo: Tanit Thorne

Leave a Reply