I am an undergraduate student sinking in financial debt.

Getting up in the morning has been grueling because I know that I am paying a tremendous amount of money, and for what? Unemployment? That’s a petrifying thought. Questions bombard me of whether my career choice is worth it, despite the fact that I love it. Will my education be beneficial even if I don’t find a job right away? Or am I going towards my demise? How can I value my education with debt and unemployment looming over me?

The value of education has been spinning around my head like cartoon birds. I enjoy what I’m learning, yet a part of me feels disconnected from my studies. Naturally, I went looking for an answer.

Is this the value of education? A person’s life?

My thought process began with unemployment. If after my undergraduate studies I am unsuccessful in finding a job to pay my student loans, what is my next step? There’s always the backup plan of working in any job outside of my field, but I love learning so I began looking into graduate studies as an alternative.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Katherine Fedoroff about graduate studies. She is a University of Saskatchewan biology master’s student and she shared with me her experience as a graduate student. And quite honestly, it sounds difficult.

“You have to deal with balancing [your] scholarships with living necessities like food and rent [and your] own tuition because graduate school does cost money,” Fedoroff said.

Because of money worries, some students quit their studies indefinitely — and I don’t blame them. As an undergraduate myself, money is where I feel constrained, too.

Financial concern can compromise one’s mental health as well. A 2019 health survey indicated that two per cent of U of S students attempted suicide in the last 12 months. We’ve also seen two student deaths this year. Is this the value of education? A person’s life? I refuse to believe that; someone’s life is worth more than a piece of paper or diploma.

My search for the value of education was nowhere near its end. Thankfully, Katherine put me in touch with her dad, Mike Fedoroff, a 1990 U of S master’s graduate in mechanical engineering. It was fascinating to hear his opinions on unemployment because the rate when he convocated in 1987 was at 8.4 per cent, considerably higher compared to now at 5.7 per cent.

Because of the high unemployment rate, he said that only five out of 85 graduates from his class had job offers right out of university. That’s unbelievable. Maybe I shouldn’t be complaining since applying for jobs is easier now than it was then. With the world wide web taking a recognizable form later in 1990, Mike said that in his time you “had to either pick up the phone, write a letter or travel to the location.” His reality was not online résumés and job websites.

Even though we have it easier, I still feel uncomfortable as I approach the last year of my degree. For people under 24 years old with a post-secondary education, Canadian unemployment rates hit an average high of 10 per cent in 2016.

This means that approximately 53,200 graduates with either a certificate, diploma or a bachelor’s and master’s degree did not receive a job offer right out of school. Who knows how many more received a job offer out of their actual field, rendering their diploma somewhat useless.

All my life, I’ve been told the same thing — get a degree and you’ll be successful. I was promised success, not unemployment, so it makes me wonder why unemployment is a frequent reality for convoked students.

According to a 2012 survey, 31 per cent of employers said that university alumni were unprepared for their job search. On top of that, there are more students graduating than skill-intensive jobs being created, adding to the unemployment rate for youth. Also, employers are saying that students are graduating from universities lacking skills in oral and written communication.

It’s absurd that an institution for higher education would fail its students in preparing them. Newly-convoked students may have a higher education, but what use is a degree if they can’t properly communicate? Knowing the anatomy of a human being or finding the x in an equation doesn’t mean shit if you can’t converse properly with your colleagues.

I feel like I am closer to figuring out the value of education. Nigel Leach, an environmental engineering 2017 alumnus, was the next person I spoke to. When I asked him about jobs, he showed me a new perspective. Leach talked about the people running companies, saying that they are the ones who didn’t have As or Bs “but the ones who [had] Cs and Ds.” To me, these are the people who spent time in extracurriculars and professional development.

My education is a good start to getting a job, but it’s investing in how I will stand out from other applicants that will get me my dream job and lifestyle. But that will not matter if professional colleges are churning out more convocated students than there are skill-specific jobs in the workforce.

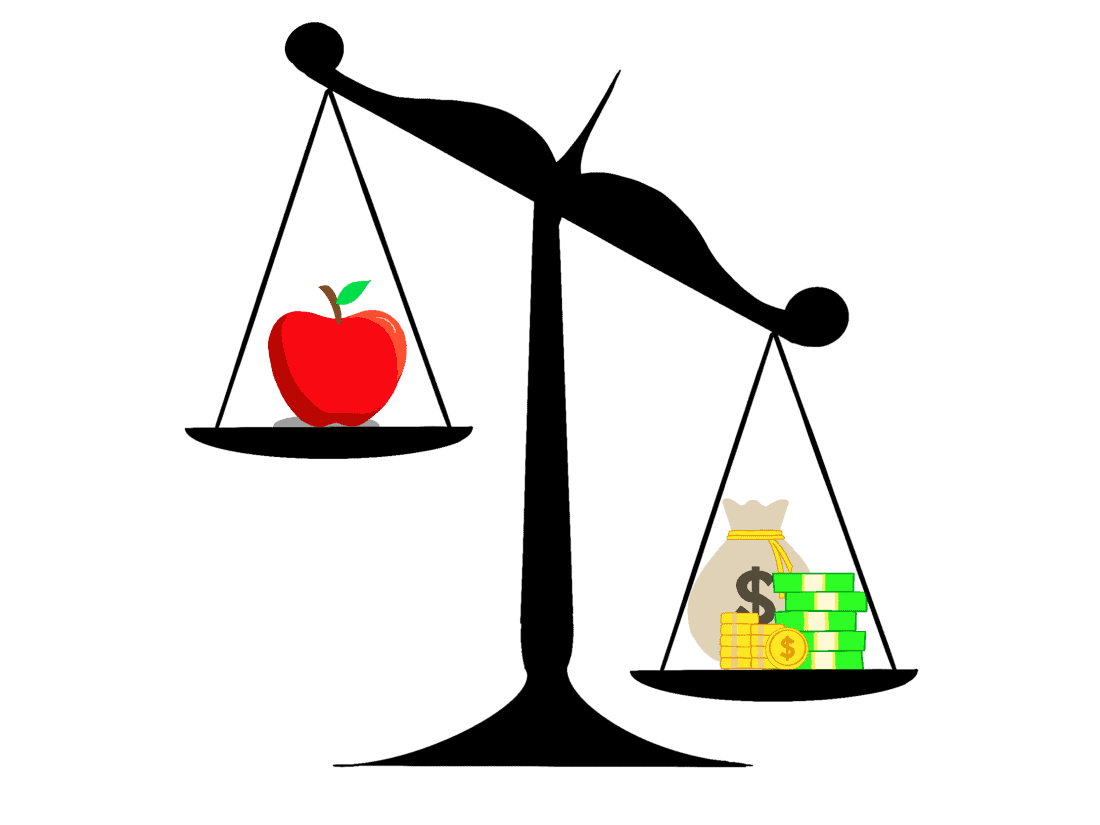

At this point, I can conclude that education is valuable. The reason that students attend universities is because you can have a higher paid job. Yet I am beginning to question — not the value of education — but the purpose of it, because I still feel disconnected from my studies. Am I the only one that feels like the purpose is for money only?

I am not. Akinwande Akingbehin is a psychology and international studies major who expressed the same opinion, as did Abhineet Goswami, a physiology and pharmacology student. Both of them led me closer to the truth I’ve been approaching — that what universities do now is for the purpose of profit and getting more workers out there instead of education for personal freedom.

Knowing the anatomy of a human being or finding the x in an equation doesn’t mean shit if you can’t converse properly with your colleagues.

“These institutions are not necessarily to educate you. These institutions are … to create a culture of working for the industry,” Akingbehin said. “[If] you want to be a doctor, they train you to be a doctor.”

“They don’t train you [on] why you are becoming a doctor,” Goswami quickly added.

The purpose of education is diluted in today’s university culture. Akingbehin is right to ask, “What’s the purpose of education, for God’s sake?” Today, it is being defined as a way to receive jobs, not to learn. Some students are going into medicine or another high-paying career for the sole purpose of money, not because they aspire to help people.

We are seeing education for economic enrichment rather than human development. I believe that problems such as corporate greed and unethical behaviour happen because we don’t have a sense of education for freedom. This is an idea that focuses on the discovery of one’s perspective through education, yet this is being ignored.

It doesn’t help that students are prioritizing grades over learning. With such a standardized system, students will always find ways to cheat to get the grades they want. I can attest that even when it’s an open book test, students cheat and whisper answers to one another. Some will attain their diplomas or degrees without actually learning the importance of their knowledge.

I don’t blame the students for cheating either. We are taught by professors who don’t have teaching skills. The very people who we are supposed to look up to for education are instead reading off facts from a book, copy and pasted into a PowerPoint slide. I might as well just read the textbook instead of paying $600 for this kind of teaching.

Because of mass education — a perspective similar to mass production — we have graduates who fail to develop basic communication skills. Students are so busy securing a high enough grade that once they actually go into the workforce, they still don’t have the traits that employers are looking for, such as oral and written communication.

Since recent graduates can’t find jobs in their respective careers, they take any job they can find. That’s how they become a barista with a $70,000 law degree.

For those of you who got great grades through dishonest means, I’ve got bad news for you. Did you know that if you participated in academic dishonesty, you’re more likely to commit workplace dishonesty? Studies have shown that you are likely to do such deeds, especially if the reasons you cheated are because you did “not [have] enough time,” “grade pressure” or because “the professor deserved it.”

All of these problems stem from education for profit. I was so worried about unemployment when I should have been worried about whether I understand the importance of what I am learning. Upon realizing this, I can’t help but be concerned that universities want more and more students to enroll each year. These educational institutions are recruiting youth with cliché slogans and promises of wealth.

What if universities start teaching for the purpose of education for enlightenment instead of for profit? We can look at Finland. There, education is free, and citizens have the freedom to use their universities for what it’s built for — learning and discovering yourself. They value teachers and what they have to offer. In fact, teaching is a respected profession and a highlycompetitive career there. Doesn’t that sound nice?

Universities are built on the backs of suffering students yet they fail to teach us the most basic key to success — that the purpose of education is not for business but to discover yourself.

—

J.C. Balicanta Narag/ Copy Editor

Graphics: Shawna Langer/ Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply