When going to the movies, there are certain expectations that we take with us along with our car keys and wallet.

There should be someone on the other side of the counter to buy our tickets from. We will be sold overpriced popcorn while seeing peoples’ poor attempts to sneak in outside food to avoid said overpriced popcorn.

All of the toilet stalls will be filled when you try to take a quick washroom break right before the best part of the movie.

With so many expectations, we don’t always pay attention to our feelings.

Consider the excitement that builds when going to the movies. Maybe it’s a Friday night and you’re going to the Roxy. As you walk towards the glowing red and blue marquis, a feeling of anticipation builds.

It begins with a slight shiver. Whether it’s from adrenaline-fuelled excitement or just how damn cold it is in there, you’re not quite sure. As you find your seat in the theatre with the lights on the Roxy’s blue ceiling twinkling like stars, the spark of anticipation ignites.

The lights dim, the crowd quiets down and for just a few hours, you’re in a different world.

The waves of emotions as the audience collectively react to the highs and lows of the movie, the comedown that happens with the closing credits. The squinting eyes as you walk into the bright lobby — paired with slight disbelief that the world continued on while you took a short recess from it — all of it adds to what makes the experience so unique.

It doesn’t hurt that the Roxy is so nice to look at, either.

The theatre experience of the present wasn’t built in a day. It reflected the events of the early 20th century. With nationalist tensions rising and rights being fought for, there was a lot of uncertainty floating around the world. Old ways of life were being thrown off and people didn’t know what to make of it.

Change was the zeitgeist, and the art of the time reflected this sentiment. Entertainment served as an antidote to their worry, and places like the Roxy gave people a break from an ever changing world.

Many art forms were moulding their own take on the state of the world, using ideas rising out of movements like modernism, impressionism and expressionism. These all found a home in theatre.

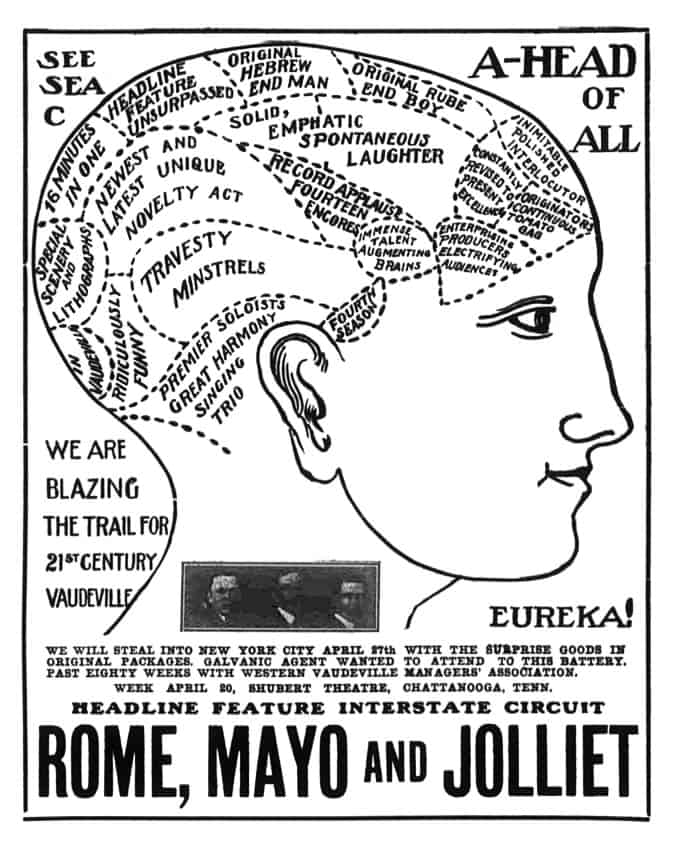

All the stresses of the real world weighed down on people and they were on the lookout for a lighthearted ticket to a place where all of their worries would melt away. It is for this reason vaudeville — a variety act that could consist of anything from burlesque to comedy to music — reached its zenith in the 1920s despite having been popular since the 1890s.

Described by American author, media theorist and culture-critic Neil Postman as the theatrical equivalent of dadaism, vaudeville was disjointed and ridiculous — the entire thing was a farce.

Its acts ranged from the wildly talented to the mildly interesting. It was the absurdity that characterized it and made it so popular in a world that was changing so often that meaning and reason were often out of reach.

Vaudeville found its home in theatre, the hours would fly by with the ever present laughter that its shows inspired. Despite its absurdity, vaudeville was an art form that was crafted for the entire family to enjoy.

It was here we begin to see the rise of the not quite placeable feeling that came with going to see a show. Entire families would make lasting memories at the theatre laughing along with strangers at acts ranging from a quintet of singing women to a monkey riding a bicycle.

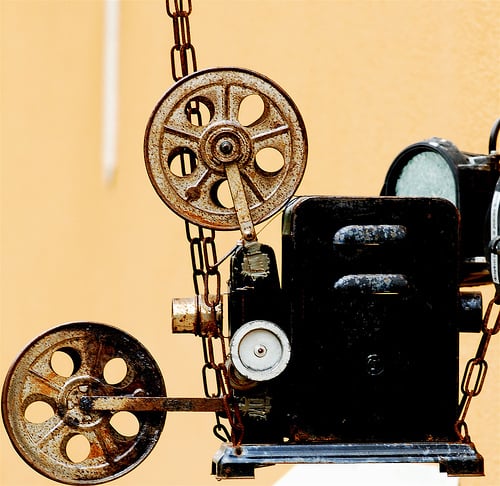

Unfortunately, good things don’t always last forever. The decline of vaudeville came with the end of the roaring 20s, its place taken by black and white cinema. It is almost ironic that a form as jaunty as vaudeville began to die with the 20s, a time characterized by its buoyant vivacity.

Though there was no decisive end to vaudevillian theatre, it definitely faced a steep decline. Soon, every vaudeville playbill included cinema. As vaudeville tapered off, it gave way to a golden age of cinema that lasted through to the 1960s.

People living through this golden age had a lot on their plate. With the Great Depression, World War II and the start of the Cold War happening within the span of just a few decades, movies were a cheap getaway from the mundane drudgery of daily life.

On cold nights when the radio seemed to only broadcast bad news, the cinema was the place to be. For a few hours, you could be a different person or cease to exist altogether. Before long, it was the most popular form of entertainment.

Vaudeville theatres began to screen films because it was a cheaper option and its performers were drawn to the cinema because of the better wages and less rigorous working conditions. With movies, you didn’t have to pay live performers and movie characters couldn’t call in sick or twist their ankles halfway through the show.

In the end, cinema killed the vaudeville star. Or at least, badly injured it.

With the playing field levelled and theatres unable to compete with each other by boasting more extravagant or exotic shows — because they were showing mostly the same movies — theatre owners began to look for different ways to set themselves apart.

This competition manifested itself in luxurious and swanky building which borrowed heavily from Spanish style architecture.

There aren’t many physical manifestations to the golden days of vaudeville or the transition of public preference to cinema, especially in Canada. There are some vintage posters advertising apparently stupefying shows and old photographs showing smiling, singing women but not much else.

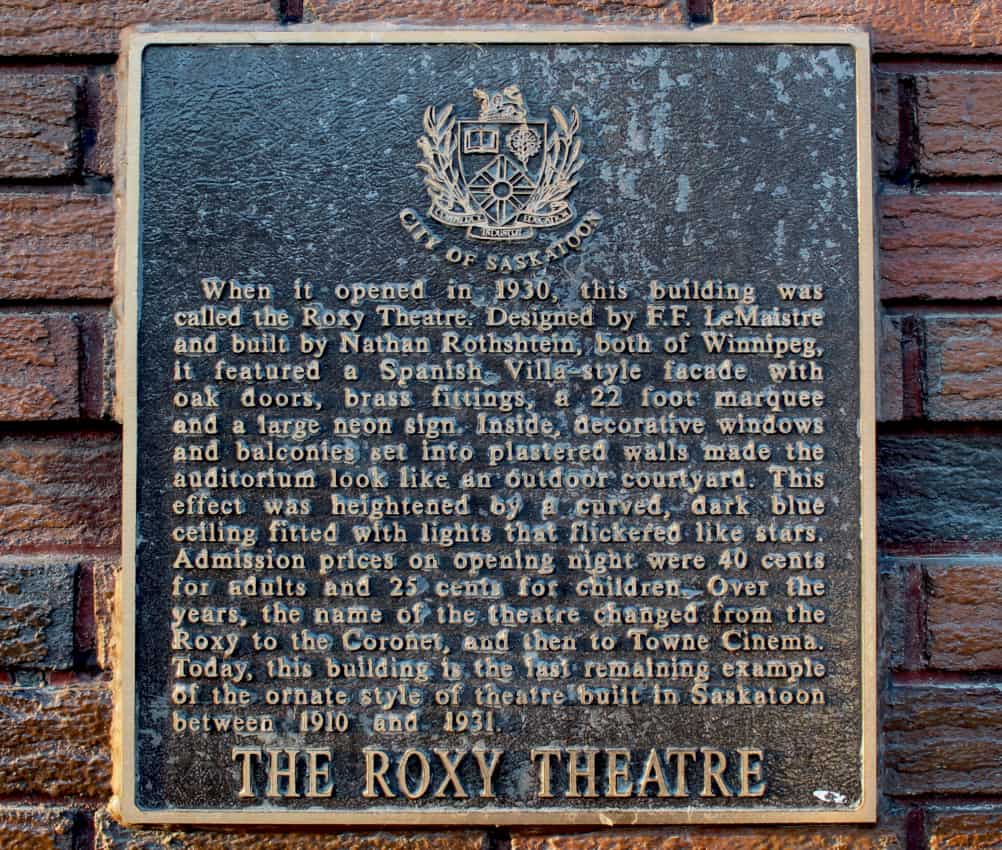

This is why Saskatoon’s own Magic Lantern Roxy Theatre is such a historic building. Opened in 1930 as vaudeville was dying out and cinema was on the cusp of its popularity, the Roxy Theatre was a bridge between two worlds.

The now-demolished Capitol Theatre was opened in 1929 as a fully functional theatre equipped only for live shows — like vaudeville. The Broadway Theatre, opened in 1946, was a misnomer as it was a cinema, not a theatre.

The Roxy was a cinema-theatre, which combined elements of the fading vaudeville era and the imminent age of cinema. It was a bridge between two distinct times: it ushered in the new age of entertainment while paying homage to the previous one.

This theatre is an important piece of local entertainment history. The murals on its wall — done by Canadian artist Fred Harrison — tell the story of a different life. A time where a trip to the movies would put you back 40 cents an adult and 25 a child.

There are few other buildings left in Saskatoon and even Canada that have weathered the test of time while retaining its essence. Having gone through many renovations in its life, it is remarkable how much of the theatre’s original features have been preserved.

The balconies and windows in the theatre that allude to Spanish courtyards and ornate marquee hanging outside of the building still stand today like they did almost 90 years ago. Even the blue ceiling peppered to look like the night sky is the same.

Despite everything cinemas like the Roxy did to draw people in, easily accessible television dealt a heavy blow to the theatre industry. Though there is an abundance of modern theatres across Canada, the Roxy is only one of four original atmospheric theatres still standing that embody the spirit of the times it was built in.

This past March, it was recognized by Saskatoon Heritage Society as historically significant, labelling it an architectural landmark to be treasured and celebrated.

Despite the heavy blow dealt to cinema by on-demand television, it continues to grow and change and find new ways to tickle our fancies. The days of grandiose impresarios are gone but a renaissance of cinema can be found in today’s culture.

In Saskatoon, there is a movement being made to partly rebuild the old demolished Capitol Theatre. Movie blockbusters remain ever-popular and for some reason, we keep going back to the movies and paying for that overpriced popcorn. At this point, it’s just part of the experience.

With the diversification of film genres and new angles and ideas being put on the screen, cinema remains ever changing. One thing is still the same, however — the same escapism that drew people to the cinema in the early 20th century is still at work today.

—

Tomilola Ojo/ Culture Editor

Photos: Tomilola Ojo/ Culture Editor, Mike Lunde/ Flickr, Al Q / Flickr

Leave a Reply