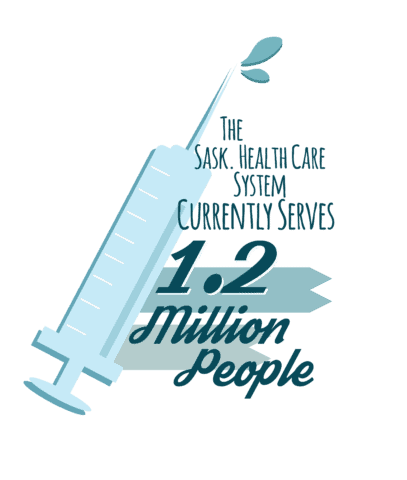

Although many of us have interacted with the Saskatchewan health care system as patients or employees, most of us probably do not contemplate the ways in which it is organized. However, this hidden aspect of the provincial health system is about to undergo a major shift — one that will affect the people of Saskatchewan in a variety of ways.

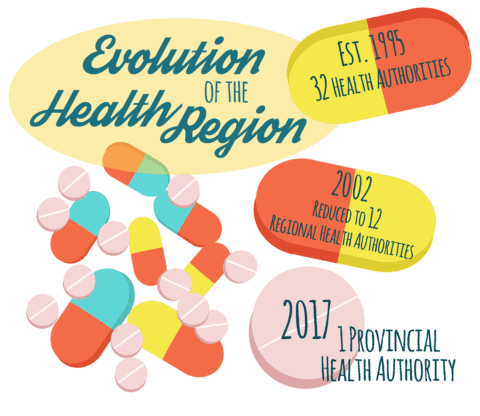

On Jan. 4 Health Minister Jim Reiter announced that the province would move to consolidate the 12 existing Regional Health Authorities into a single Provincial Health Authority by the fall of 2017. This transition is based upon recommendations issued by the Saskatchewan Advisory Panel on Health System Structure.

The goal of this move is to improve patient services across the province as well as improve administrative efficiencies.

For Tom McIntosh, head of the department of politics and international studies at the University of Regina, the move to a singular health authority came as a bit of  a surprise.

a surprise.

“[The advisory panel] had a clear mandate to make a recommendation to reduce the number [of health regions]. My own thought was that they would come back with maybe three or four, not including the one in the far north,” McIntosh said.

This recent move is the latest in a long history of health region amalgamation within Saskatchewan. The number of RHAs was reduced to 12 in 2002 from an estimated 32 in 1992.

Saskatchewan is currently divided into 12 RHAs, each with its own regional governing board and administrative operations.

Additionally, Saskatchewan also includes the northern Athabasca Health Authority, which is administered jointly between the provincial and federal governments to serve the residents of the Athabasca Basin. Because of its unique status, the Athabasca Health Authority will not be included in the consolidation of RHAs.

The Advisory Panel was formed in the summer of 2016 with the purpose of providing guidance to the provincial government on the restructuring of the health care system.

The Advisory Panel came back with a document titled Optimizing and Integrating Patient Centred Care. The document outlined four main priorities or mandates for health care reform within Saskatchewan, as well as recommendations on how to achieve those priorities.

“The key argument for the panel was the quality of care and the ability to better co-ordinate and integrate care from a more centralized way,” McIntosh said.

McIntosh cited emergency ambulance service as an example of something that could be vastly improved with centralization. Currently, each RHA contracts its own  emergency services, and it is the RHA that determines which ambulance attends an emergency, not distance.

emergency services, and it is the RHA that determines which ambulance attends an emergency, not distance.

“There may actually ambulances that are closer to you, but that won’t be the ambulance that comes to get you because between you and that closer ambulance is the border of a health region and their contract doesn’t go across that border,” McIntosh said. “The hope is that without those borders, we can negotiate a series of contracts that would not allow that sort of thing to happen anymore, and that you would get the ambulance that is available and closest to you.”

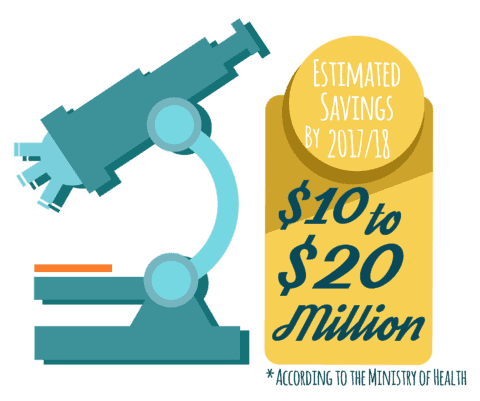

While the main benefits of consolidation cited by the Advisory Panel are related to the improvement of administration and the delivery of health-care services, monetary benefits were also mentioned.

According to the CBC, a spokeswoman from the Ministry of Health later announced that the new singular health authority could save the province nearly $10 to $20 million by the 2018-19 fiscal year. With the Saskatchewan government currently managing a nearly billion-dollar deficit, the province will be looking to save money anywhere that it can.

Despite these claims, McIntosh is skeptical about howl much consolidation will really save the province.

“When they announced this, the [advisory panel] didn’t talk about saving money. The Minister [of Health, Jim Reiter,] talked about saving money. I don’t think they’re going to save a penny,” McIntosh said.

He cites the results of health region consolidation in other provinces as evidence to this claim.

“Alberta, when they went to one region, did not save any money. B.C. has reduced the number of regions, Nova Scotia has reduced the number of regions, New Brunswick has reduced the number of regions — none of them can point to significant savings,” McIntosh said.

Aside from fiscal issues, various groups have expressed other concerns with the consolidation of the 12 RHAs.

Rural and northern communities are concerned with ensuring that they have adequate representation within a larger, less localized governing body. The CUPE, which represents nearly 13,000 health care employees within Saskatchewan, is concerned about potential job cuts or wage reductions. It is an issue that extends to every corner of the province — literally.

While these changes to Saskatchewan’s health care system undoubtedly affect students on an individual levels as citizens, but how do they affect us as a university?

The U of S is home to numerous academic health sciences programs, ranging from the College of Kinesiology to the College of Medicine. Most health sciences students will spend a portion of their program studying within the health care system and many will eventually find employment there as well.

With these ideas in mind, the U of S College of Medicine was among the many groups that were consulted by the Saskatchewan Advisory Panel on Health Systems Structure, providing both a written brief and an oral presentation.

For Dr. Preston Smith, dean of the College of Medicine, there were two main priorities for the university in regards to Health Authority consolidation: academic mandate and physician leadership.

Smith emphasizes that a single Health Authority would help standardize practices and treatment of health sciences students and medical residents, creating a more streamlined environment for teaching and education.

“One main theme was that the health region, however it’s configured, that the academic mandates of teaching and research are well embedded in the new health region [and] recognized by the health region. Ideally, we would see an evolution of the health-care system to really be what’s called an ‘academic health sciences network,’” Smith said.

In regards to physician leadership, Smith would like to see doctors take a greater role within the management and administration of health-care services, especially with students.

“In our case, we wanted the new model of physician leadership to integrate both the academic and the clinical leadership. So when a doctor in Saskatoon, or Estevan, or Regina or Prince Albert has got a student in front of [them] or a student issue to deal with, [they] know whom to call, about who’s responsible from an academic perspective and who’s responsible from a clinical perspective,” Smith said.

Ideally, the health system will be able to address the needs and concerns of both students and patients, says Smith.

“So we really emphasize that need to have a strong physician leadership model that could bring about the change that the health-care system needs, and also integrate into that whole discussion the needs of our learners and the needs of our patients,” Smith said.

Overall, Smith is satisfied with the level of input that the U of S has been able to contribute to the transition of health-care services within Saskatchewan.

“One of my key messages, even last week in Regina when I was in the Ministry of Health talking about this transition, is that we need to pay attention to all of the details and we need to make sure that in no way does this transition negatively impact our learners,” Smith said. “I think they’ve heard the message, they’ve been listening and I’m confident they’ll make it happen.”

—

Emily Klatt / Sports & Health Editor

Infographics: Lesia Karalash / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply