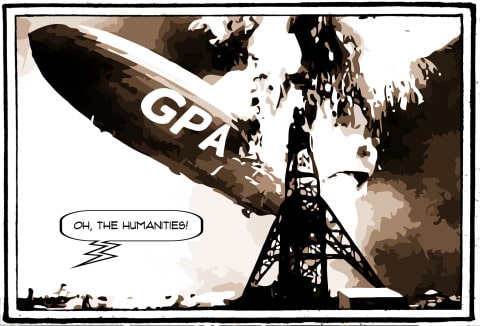

Whether for scholarships or for postgraduate admissions, grades matter for high-achieving students. Yet, top students in the humanities are getting a raw deal when it comes to their grades.

It’s commonly understood that science-oriented courses are typically graded more objectively than humanities courses. While a mathematics problem or multiple choice question is either correct or incorrect, a written assignment is usually more nuanced.

It’s possible for a student to get 100 per cent of their math problems correct, but humanities instructors symbolically hold onto the idea that there is always room for improvement and that a “perfect essay” does not exist.

exist.

For these reasons, top students in the humanities are met with an effective ceiling on their potential grades, which students in the sciences do not experience. Top science students are able to achieve higher averages than top students in the humanities. This hesitancy of humanities instructors to dole out perfect or near-perfect grades hurts their top students in meaningful ways.

One way this grading disparity between disciplines is apparent is in the distribution of scholarships and awards. There are many awards for which students across many disciplines compete, and an important component — if not the only one — for selecting the recipient is based upon grades. In this area, humanities students are placed at a distinct disadvantage.

Take, for example, the Governor General’s Silver Medal, perhaps the most prestigious award for undergraduate students bestowed at University of Saskatchewan convocations. The Silver Medal is awarded to the undergraduate student or students with the highest academic standing — essentially, the highest overall average.

At the past nine spring convocations, there have been Silver Medals awarded to 12 students graduating with a collective 15 degrees. Of these 12 students, 10 graduated with at least one bachelor of science.

Only one student graduated with a bachelor of arts — and that student also graduated with simultaneous science degrees. Does this discrepancy suggest that top sciences students are higher-achievers more regularly than top arts students, or is it more likely that this difference reflects an unequal playing field when it comes to grading systems?

The issue of awards raises a related issue — one of representation. When top awards regularly go to science students, our perception of students who are high-achievers is impacted. Arts students are less visible when all disciplines are compared and awards are distributed — areas of study are not represented proportionally.

This reinforces a negative narrative about students in the arts — that they are less hardworking, less intelligent or otherwise lesser academics in comparison to their peers in the sciences. A change in grading practices would help alleviate this negative light in which humanities students are often perceived.

Awards and scholarships are not the only practical issue resulting from this grading disparity. Competition for non-direct entry programs is also significant. Humanities students are put at a disadvantage when applying to programs like law or education.

While some of these programs in Canada take into consideration the way in which different disciplines are graded, many do not. In my own experiences, some institutions make admissions decisions largely based on a mathematical algorithm — in which one’s grades play an enormous role — and one’s disciplinary background is largely irrelevant.

High-achieving humanities students will probably find it more difficult to gain admittance than their similarly competitive peers from the sciences, simply because the disciplines grade differently.

As a humanities student myself, I am not calling for arts instructors to change to an objective grading style or to implement more multiple choice exams. Still, I think real changes must be made to help humanities students compete fairly with students in other disciplines.

Perhaps a good place to begin would be to reconsider the ceiling instructors place upon grades in humanities courses. While the aversion to give out near-perfect grades carries an important message, instructors could explore alternate ways of getting this message across while recognizing that their field does not grade in a vacuum.

Until changes occur, humanities students will continue to be disadvantaged when competing for both tangible accolades and for respect amongst their fellow undergraduates.

Leave a Reply