NATALIE SERAFINI — The Other Press (Douglas College)

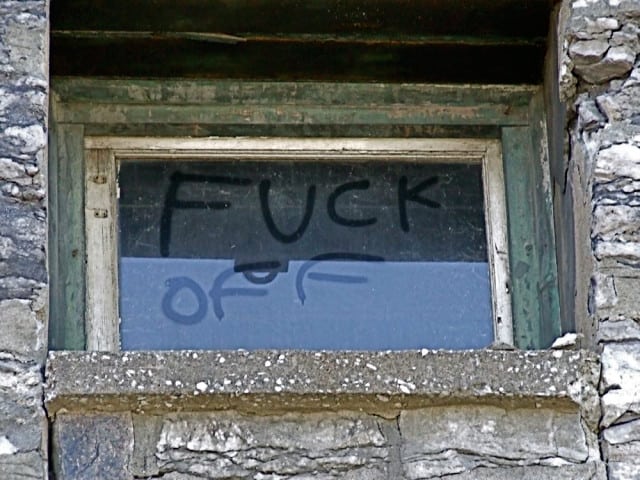

Kids probably wrote this, so why are you scared of saying something they’re writing on your goddam house?

NEW WESTMINSTER, B.C. (CUP) — When I first met my nephew, there were a lot of things I worried about. I worried I would drop the precious bundle because I had no idea how to hold a baby. I worried I had a rare genetic disorder that would cause me to drop the baby every time I tried to hold him.

More than these entirely rational concerns, though, I was especially worried that I would slip-up and drop an F-bomb in front of my infant nephew.

So I confess, I worry about swearing in front of kids. Yet I can’t think of a reason why the cleanliness of my speech should be a concern around children.

What are we trying to protect? Perhaps it’s due to the innocence we see in them. The innocence that allows kids to believe in Santa Claus and the universal understanding that nothing should pierce, stab or crush the delicate exoskeleton of that dream.

Let’s assume it’s innocence that we’re trying to preserve when we swap out our typical curse words for “fudge” and “sherbet.” Hearing swear words doesn’t tear children out of childhood and set them on the path toward a hard knock life. Kids aren’t born with an innate understanding of what those words mean, so uttering a few choice syllables isn’t going to open a veritable Pandora’s box of hardship, and it likely won’t give them a case of Tourette Syndrome, either. It’s difficult to see how the utterance of a few words would mar a child’s innocence, so I’m hesitant to give that explanation full credibility.

Instead, perhaps the concern is in ensuring that the child’s vocabulary is suitably broad. It wouldn’t be good if the child were to use swear words to describe everything, or peppered every sentence with curses.

But when a child learns a new word, do they apply it to every single situation and sentence?

I’m sure some kids do, but it’s not guaranteed that an obscenity will become their new favourite word — especially if parents calm down and stop worrying about their kids getting overly attached to a swear word.

Kids frequently only become fascinated by things that carry some mystique or that are taboo. If one doesn’t assign impropriety and illicitness to the words, a child will likely forget that they even heard a curse word.

And if the concern is with expanding the child’s vocabulary, the easy solution to that is to expand your own vocabulary and not swear in every sentence. That doesn’t mean never swearing — sometimes “fudge” or “sherbet” don’t quite address the enormity of a situation — but choosing to be strategic and effective.

There are certain things kids should be protected from: polio, murderers and drugs, alcohol, cigarettes; life- and quality of life-threatening forces that go under the parenting guidelines as “to avoid.”

Language is not one of the things kids should be protected from.

Language is powerful, and rather than ignoring the existence of words, maybe it’s better to teach kids to understand their significance. There will be a few rogue rascals walking around the grocery store shouting their favourite new curses, but generally speaking, the kids won’t care about their new-found knowledge.

Parents should be teaching their kids to have an arsenal of words at their disposal, even if that means emphasizing the sparse use of some words.

—

Photo: Racneur/Flickr

Leave a Reply