As Canadian universities try to balance their budgets in the face of a sluggish economy, students have seen their tuition go up by eight per cent in the last two years.

As Canadian universities try to balance their budgets in the face of a sluggish economy, students have seen their tuition go up by eight per cent in the last two years.

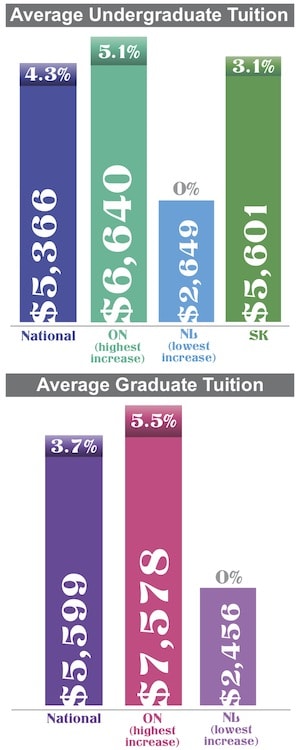

A four per cent increase for the 2010-11 year was followed by another 4.3 per cent hike this year, according to a recently released Statistics Canada study. The Canadian average for undergraduate tuition is now $5,366. Ontario students, who pay $6,640 on average, pay the highest tuition in the country. Nearby, Quebec students enjoy the lowest tuition in the nation, paying an average of $2,411.

However, tuition isn’t the only way schools get more money from students. Tuition in Alberta is nominally capped to the Consumer Price Index, meaning it increased by about two per cent for the 2011-12 year.

“However, that number is misleading,” said Farid Iskandar, University of Alberta Students’ Union Vice-President External. “Alberta has the highest mandatory non-instructional fees levied on students in the country: they’re $1,399.”

Non-instructional fees pay for such things as athletics programs and maintaining campus infrastructure.

While Alberta has the highest fees, students in New Brunswick will have the largest increase over last year’s non-instructional fees for both graduates and undergraduates. That province is just leaving a three-year tuition freeze. Compulsory non-tuition fees went up for undergraduates by 21.5 per cent over last year, though they only jumped to $430. For graduate students, non-instructional fees went up by 17.6 per cent.

The national average for compulsory fees was a 5.5 per cent increase for undergrads. Graduate students in Nova Scotia were the only students in the nation to see a decline in compulsory fees; they went down by 7.5 per cent.

In addition to compulsory fees, Alberta has instituted “market modifiers,” which allow certain colleges to increase their tuition by more than CPI. For this year Iskandar said the colleges of business, engineering and pharmacy were among the schools to receive approval.

“The CPI cap is a good move,” Iskandar said. “But the CPI cap is not reflective of the actual cost of education.”

These fees are another way for cash-strapped schools to close gaping budget holes while still adhering to tuition regulations. But the fees create problems for students, Iskandar said.

“Alberta has the lowest participation rate out of all the provinces [for university attendance]. We don’t see things like breaking the tuition cap helpful to increasing accessibility.”

While Canadian undergrads are paying more each year, they are still significantly better off than either their international student counterparts or graduate students. International students, who represent a rapidly growing demographic of the student population, pay an average of $17,571 in tuition. This is up 9.5 per cent from two years ago.

“We need to keep the tuition cap” and implement it where it is not already in effect, Iskandar said. “But we also need to regulate non-instructional fees”¦ so students can expect and plan for the cost of education.

“Things like academic materials [which have increased in price by 280 per cent in the last 10 years] and rent are harder to plan for when you don’t know exactly what your tuition will be.”

Average undergraduate tuition at the University of Saskatchewan is $5,610 per year and increased three per cent over last year.

—

graphic: Brianna Whitemore/The Sheaf

Leave a Reply