Taking care of one’s self often becomes low on the list of priorities for university students. But neglecting mental and physical health can be dangerous, especially when it comes to eating disorders — and University of Saskatchewan students are no exception.

Feb. 1–5 is Eating Disorder Awareness Week at the U of S. Eating disorders, which are often stereotyped, are part of the messy and complicated web that is student mental health. Discourse at the U of S surrounding more common mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression has improved over the last several years, but those who suffer from eating disorders are still getting lost in the crowd.

What do you picture when you think about someone who has an eating disorder? The first image that comes to mind for many is that of a thin, pale teenage girl with protruding ribs, hovering over a scale. Include self-induced vomiting for a bulimia variation.

Despite the commonality of this image, eating disorders are far more complicated than just avoiding food. They encompass a wide range of symptoms and sufferers, both of which can be difficult to recognize.

to recognize.

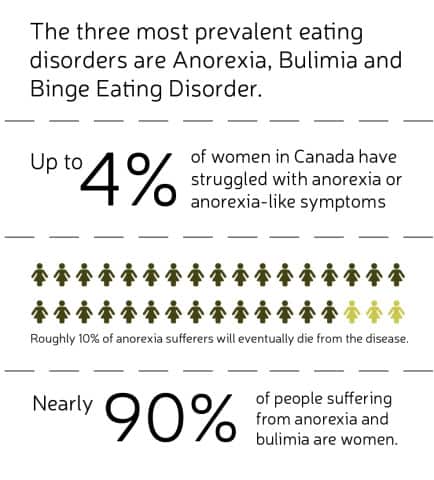

The three most prevalent eating disorders are anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder. Anorexia pertains to the severe restriction of food in order to lose weight or avoid weight gain. Bulimia is marked by periods of binging — consuming a large amount of food in a relatively short time — and purging, often by vomiting, in order to get rid of calories consumed. BED involves the binging aspect of bulimia, but not the purging. Any behaviour that doesn’t fit into one of these three categories is labeled as an Otherwise Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder.

There are certain factors about a university environment that make young people particularly vulnerable to the development of eating disorders. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, the vast majority of eating disorder sufferers begin to struggle during the transitional time between adolescence and adulthood.

Emma*, a fourth-year arts and science student at the U of S, is among the up to four per cent of women in Canada who have struggled with anorexia or anorexia-like symptoms. She can trace the beginnings of her eating disorder back to her time as a high school student.

“I would have been in grade 11 when it sort of started. I was kind of — not overweight, but definitely a little bit chubbier growing up. I just really liked food,” Emma said.

Unhappy with the way her body was, Emma sought a way to change her appearance — a quest that began innocently enough.

“I just wanted to do something about it. I also danced, and had gained a bunch of weight from eating fast food and was not happy about it. So I decided that I would go on a diet, lose a few pounds and then go off of it. But that didn’t end up happening. I didn’t really notice at first, but it just sort of escalated from that point,” Emma said.

She soon began to restrict both the amount and the type of food that she consumed. Using a vegan diet as a mask, Emma was able to cut out most foods except fruits and vegetables. She also used laxatives as a way to compensate for what she ate.

Unsurprisingly, Emma lost a lot of weight. This unhealthy pattern continued throughout the rest of high school, but it was when she entered her first year of university that things really began to spiral out of control.

“I would say that I was very obsessive about it, like keeping a daily journal and also starting obsessively exercising,” Emma said. “I wasn’t really obsessively exercising in the beginning but when I started university, the exercise also became a factor. I was doing these super intense cardio workouts every day for like, an hour, but also hardly eating anything, so trying to have no caloric intake at all.”

What exactly is it about the university environment that can cause or worsen eating disorders in students? Starting university is usually a time of massive change in one’s life. Many students change cities, move out of their parents’ homes or find themselves without structured meals and someone to hold them accountable for their actions.

This newfound freedom can allow students to grow in a number of positive ways. However, it can also contribute to the development of an eating disorder.

“The first year was just sort of a lonely experience. You’re doing way more things by yourself. I went through high school with the same group of girlfriends that I’d had since elementary school and I’m still friends with, but [going] from seeing each other every day to not seeing each other [as much] was a huge shock for me,” Emma said.

Eating disorders are not a problem to be taken lightly. According to the National Eating Disorder Information Centre, roughly 10 per cent of anorexia sufferers will eventually die from the disease. This makes it the psychiatric disorder with the highest mortality rate.

Even for those that live, all types of eating disorders can cause significant long and short-term health risks, ranging from heart problems to vocal cord damage to osteoporosis.

One of the hardest parts of having an eating disorder is not being able to recognize just how sick you really are. The illness distorts reality, making it difficult for eating disorder sufferers to seek out help, even when that help is readily available.

The U of S currently offers counselling through Student Health Services. To be eligible, students must be registered in at least one course during the current term. It is also possible to access a dietitian and a psychiatrist upon the recommendation of a general physician. All of these services are free to students through their tuition fees.

There used to be a student group run specifically for those who have eating disorders at the U of S, called the Usask Eating Disorder Support Group. However, according to the group’s Facebook page, they have shut down their services due to low attendance. Those struggling with eating disorders must now look elsewhere for specialized support.

This begs the question, why are students with eating disorders so reluctant to seek out treatment? Part of it is certainly that the illness itself makes the sufferer unaware of their problem, but there are other factors at play.

It may be that some students aren’t informed about what services are available to them. It wasn’t until a friend guided Emma towards student counselling that she was able to talk about her problems.

“I didn’t even know that the counselling was free. I went to inquire about it, because I thought maybe it was reduced rates, but then found out it was free and got in that way,” Emma said. “Other than that, I did see something about the eating disorder support group, but I was also in a state of denial [where I thought] ‘I don’t have an eating disorder’… so I did not seek that out at all.”

Luckily, Emma was able to see both a counselor and a dietitian through Student Health Services. Recovery isn’t a straightforward process, but she feels as though she now has a good understanding of what behaviour to watch for in herself and how to prevent a relapse.

“I think that it comes back in moments with lots of change, or where there’s lots of new stuff happening or I’m feeling really anxious about things … I would say that maybe it’s not completely gone, but it’s not affecting me on a daily basis,” Emma said.

Emma represents what’s often considered to be the textbook version of an eating disorder — a teenage girl who, unhappy with her weight and striving for perfection, developed an eating disorder  as a manifestation of deeper issues. After all, nearly 90 percent of people suffering from anorexia and bulimia are women.

as a manifestation of deeper issues. After all, nearly 90 percent of people suffering from anorexia and bulimia are women.

However, not all eating disorder sufferers look like Emma. Eating disorders can be experienced by anyone regardless of race, gender, religion or physical or mental ability.

Max*, also a fourth-year arts and science student, is a young man silently coping with an eating disorder while attending the U of S. Brought upon by a severe bout of depression in high school, his illness continues to affect him in every area of his life.

“I would say that it’s close to something like anorexia, but I don’t know if that’s exactly what it is. But I’ll do what I can some days to go as long as I can without eating or without having anything, and then other days are just terrible, but I haven’t had a straight week of eating regular meals in years,” Max said.

Max has never talked about his eating disorder with anyone — not his friends, his family or even his girlfriend.

“[I haven’t said anything] because I’m still living, because I don’t feel like it’s that bad. If I felt that it was something that was causing serious damage to my health, then I would probably be more concerned, but for now it’s more of a long term functional issue,” Max said.

Despite the isolation he feels because of this unspoken issue, Max knows that he isn’t alone. However, the idea of eating disorders as a “female issue” has created a stigma around men that may suffer from them.

“I am not the only guy that I know who has these problems,” Max said. “I find that they’re actually pretty common among my friends, but we feel that we have no grounds to actually discuss that, or that we are made to feel like that’s a problem we’re allowed to have or an issue that we could possibly have to deal with.”

Max continues to deal with his eating disorder on a daily basis and it affects every aspect of his life.

“I’d say [I’m in] a prolonged state of misery. It’s something that’s on my mind if not all the time, certainly every day. It affects what I do, where I want to be, who I want to be with. It makes me uncomfortable around cameras a lot of the time — things like that,” he said.

Max and Emma are two different pieces of a complicated puzzle. Eating disorders are both a personal and political issue. The individuals are the ones that suffer, but they are all a part of larger culture that is disordered itself.

We live in a culture that actively supports disordered eating. Fad diets, extreme fitness and social media all fuel a dangerous world that is built upon lies.

Perhaps that’s why it’s so important to tell the real stories of those who have lived, and are living, with eating disorders — so that we can see the truth and maybe do something about it. Max may have said it best when he explained why he finally decided to break his silence.

“That’s why I wanted to talk to [the Sheaf], because it is a nondiscriminatory disorder. It’s not something that picks and chooses and anyone can be affected, so I think it’s important for people to understand that better.”

* To respect the privacy of the individuals interviewed, their names have been changed.

—

Infographs: Stephanie Mah / Layout Manager