“This is the philosophical tie into the ukulele: There’s a chance at connection if you put yourself out there.”

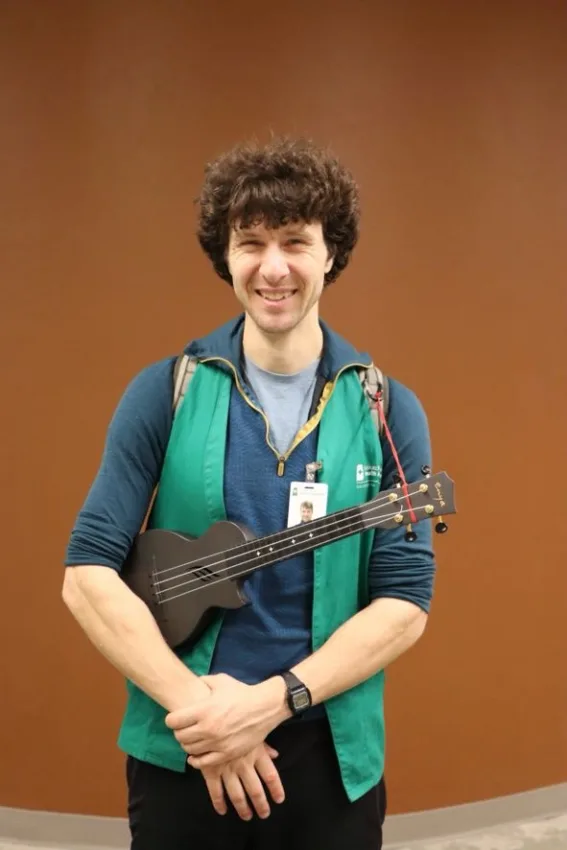

If I were to ask USask students if they knew who the Ukulele Guy was, I would venture to say that over half would know who I’m talking about.

The Ukulele Guy has become a campus legend … but who really is he? What’s his name, and why does he do what he does?

My curiosity got the better of me, and through the USask subreddit and some direct messages, I managed to find his contact information and set up an interview.

While I knew I was bound for an interesting conversation, I was pleasantly surprised that what we spoke about extended far beyond the ukulele, but into a meditation on philosophy, existentialism and connection.

The Ukulele Guy’s name is Stéphane Gerard, a third-year doctoral student studying existentialism and French literature. He comes from south of the city in rural Saskatchewan.

Gerard traces his musical roots back to his family, with experience playing the piano and violin. He is also a member of several choirs, including the USask Community Chorus and the Sherbrooke Community Center Choir.

His father got his family into the ukulele many years ago. Slowly, Gerard started bringing the instrument around more frequently.

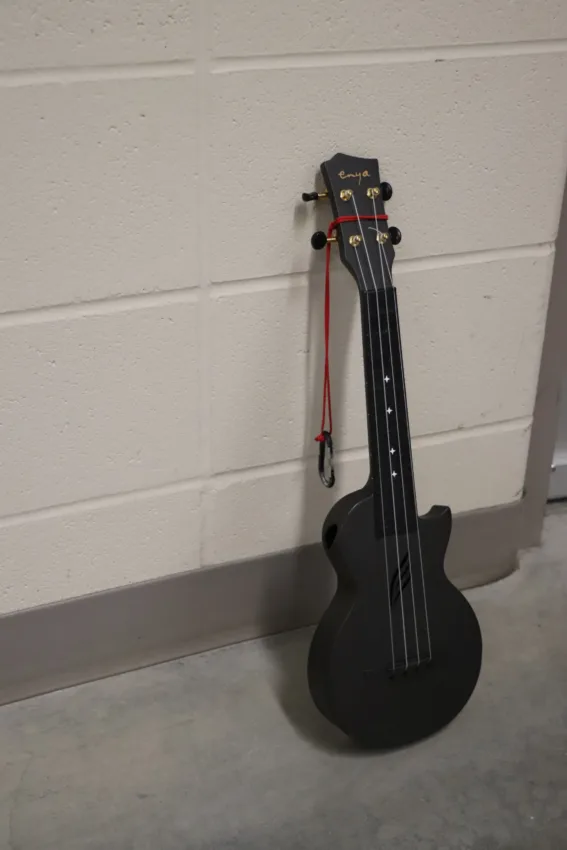

“Habitually, I keep it clipped [to] my backpack most of the time, or I keep it up in the graduate student offices … I’m still not great, but my competencies are growing.”

Gerard enjoys the challenges that come with learning something new.

“A good thing about learning an instrument is that it’s a tool for self-mastery. It’s the idea that, okay, this is difficult. I’ve not really done a fretted instrument before, and there’s a new set of skills to learn, a new set of attitudes to adopt and a new set of discoveries to explore.”

His public playing began in 2018 during his master’s degree, after he discovered the perfect location to practice.

“A few years ago, I discovered that the [Gordon Oakes] Red Bear Centre has that loop underneath where it’s an echo chamber … it has fewer corners, so the sound just keeps bouncing around and around. You can almost harmonize with yourself in that zone [with] the tail ends of your own echo.”

As a New Year’s resolution, Gerard set the goal of practicing the instrument for an hour a day, which then evolved into an hour and a half. He now tries to play every weekday from noon to 1:30 p.m., and if he shows up late, then he stays late to get in his 90 minutes of practice.

The location also allows him to be mindful of those around him:

“You don’t corner people. It’s not like an ambush. And if people don’t want any part of it, they can just walk right on by. Most people, I assume, are mildly curious, but it doesn’t change their day much one way or another. And if they, for some reason, don’t feel that that’s something that they want in that particular moment, well, 10 seconds, and then they’re on their way. The sound, once you’re out of that tunnel, fades out very quickly. And more importantly, it’s far enough away from any classes.”

Ultimately, outside of the pleasure of the experience, Gerard has the simple hope of bringing passersby some joy with his music.

“So what would I like people to take out of it? Number one, most importantly, I hope that they’re not bothered by it. Number two, I hope that they go towards their next destination with a little bit more of a positive feeling.”

Over time, Gerard has built a repertoire of over 300 memorized songs. His favourite is usually the one he’s working on, but some of the artists he mentioned were Stan Rogers, Steve Miller and Simon & Garfunkel.

When I mentioned his growing “campus-legend” status, Gerard was pleasantly surprised.

“Well, I’ll attribute that then to being solid and being regular, being steadfast and keeping a resolve. Essentially, there’s a lyric in Radiohead’s ‘Creep’ to notice when someone’s not around, and I feel like that. That’s quite heartwarming to know that I’ve built myself up to the point where it’s noticeable, at least when I’m not there.”

I also told Gerard how some students have expressed wanting to donate money for Gerard’s performances, but that is not his intention.

“Many people have assumed that it’s a busking situation, and that’s definitely not what it is. I think if there is any sort of repayment, it would be repayment in kind. I would be thrilled to see other people joining me there … I’m very flattered that people think that this would be worth money … I appreciate the compliment, but no, save your money for other, more important things.”

For Gerard, the ukulele is an invitation to connect. He encourages people to initiate conversation, make song requests, join in and sing, harmonize or bring their own instrument to play along.

“I spend a lot of time on my own, and that’s fine, but life is better when you share it with people.”

The conversations he’s had while playing have integrated him deeper into the USask community.

“I’ve made a couple of friends, and I’ve even gotten onto some Campus Rec teams. I’m quite happy for whatever adventure is going to be opened up by a random conversation … So the student clubs, and knowing what people are up to and learning something about a different college that I’ve not really had much exposure to — all of that is well within the scope of the types of conversations I’ve had. There was a fellow who came up with his guitar one day, and we had a jam session.”

Gerard doesn’t see playing the ukulele in public leaving his life anytime soon.

“This is a strongly enough ingrained pattern at this point that I very much assume that I will be doing it for the foreseeable future. Unless I can get a different outlet creatively, then, yes, I will continue doing so as long as I can, and I will do it wherever I end up in the world.”

There is also a relation between Gerard’s studies and his ukulele playing.

“There’s a direct and indirect reason why the ukulele and philosophy are intertwined. The direct reason is that I was going a little stir crazy spending a lot of time on my own, which is normal and good … [but] the mental reset [from playing the ukulele] was very valuable … and number two, the indirect reason, is that the philosophy itself is more or less about taking charge of what your decisions are.”

Outside of academics and music, exercise has been another anchor in Gerard’s life. He loves trying all kinds of sports and is heavily involved in Campus Rec. Running has also been a reprieve for him:

“When I lived with my parents outside of town, I used to run in and out of school every day, over 10 kilometres … there’s a Latin phrase, mens sana in corpore sano: sound mind, sound body. I realized that my thinking patterns were quite strongly affected by specifically the pandemic, where all the social activities and sports were shut down. And then retroactively, when I erased my calendar, I realized, ‘Oh, wow, I’ve done very little in terms of physical activity.’ And the phenomenon where you read and reread the same sentence over and over again without really absorbing it started happening to me … So let’s try to build back in some physical activity to essentially reorient myself, to be able to sit for long periods of time and read uninterrupted.”

Gerard’s running ability dates back to his time as a Huskie on the Cross Country team, competing for four years from 2008 to 2012 before beginning his master’s degree. He still has a year of eligibility left, but doubts he’ll be able to get back into the same shape as he was during his prime.

That desire for intentional living extends beyond music and exercise, including his choice to use a flip phone and avoid social media. He shares several reasons for this.

His first reason is practical:

“The accountability is much, much more direct to me, where if something is connected to real life, like for instance: I said I would be here. If I’m not here, that’s on me. That’s my word.”

His second reason is tied to reading:

“It makes me feel more connected to the authors that I’m reading who lived and thought and articulated their ideas in a time well before the internet was even conceived of.”

He also points to the social dynamics he witnessed growing up:

“A bit of a storm was kicked up on this pseudo-society online, where by the time a weekend had elapsed, two very good friends had been convinced by other people, essentially, that they were no longer supposed to be friends … I thought, ‘this is a disconnect from what really happened,’ and if someone doesn’t say something directly to you, I don’t know what the circumstances are under which they said it. So in that sense, it needs to be nuanced in person, or it needs to be reified.”

And finally, he admits the final reason with a kind of self-awareness:

“One last very important reason is that I fear the internet greatly because my obsessive mindset does not really lend itself well to even searching Wikipedia without being distracted.”

He insightfully adds: “The reality of our biology, the reality of our socialization, the reality of our upbringings [is that] we’re not raised by the internet. The internet is the thing that we’ve created, and the digital world is maybe very well realized, but only a facsimile of the world in which our attitudes and instincts and proclivities are best encapsulated.”

Gerard’s curiosity and sense of exploration have also extended into his studies.

His academic path throughout university has been anything but linear. He switched majors half a dozen times, sharing that he’d find an excellent professor and be drawn by their enthusiasm towards their specialty, but then realized that he had to find what he really wanted. He eventually finished his undergraduate degree in French Studies and then, following the recommendation of several professors, pursued a master’s degree.

This degree carried personal significance, inspired by his grandmother.

“My grandmother was working in French literature, and she was doing her master’s when she got pregnant with my aunt and uncle. She became a homemaker after that and never quite finished … So in her honour, I sort of said, ‘yeah, there’s this author that she was working on that I’d really like to explore.’ And the more I read of him, the more interested I was in this existentialist mindset [of] Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who wrote The Little Prince … I have no idea if this is exactly what she would have wanted to do, but the master’s was extraordinarily satisfying to be able to bring that to my aunts and uncles and parents and say, ‘this is sort of a full circle moment for her.’”

Gerard is now working on his doctorate and says he’ll be at USask for at least another two years. He is also bouncing back and forth between Saskatoon and Paris as he is in a combined degree program with Sorbonne University.

“I would very much hope to be in a position to try for a professorship. That would be grand if I can stay associated with academia in any way. I’ve been very, very happy here. The University of Saskatchewan has brought me many things, and if I can sort of contribute to its reputation as an educator, then I will keep walking through those doors if they remain open to me.”

To end our conversation, Gerard returned to the idea that had quietly threaded through our entire conversation: connection.

“And once again, this is the philosophical tie into the ukulele: There’s a chance at connection if you put yourself out there. You take a risk to do so, of course, but if you don’t take that risk, there’s a real threat that you go through life without ever connecting with anyone … That sensation of thinking that there’s someone on your side, that there’s someone [alongside] whom you can stare out into the void — it’s a very lonely existence if you don’t have that feeling and [a] sense of connection to other people, [a] sense of solidarity with other people, the sense of hope that’s granted by others when you’re in very dire circumstances. Sometimes the world can be a bitter and cruel place, and if you don’t have the sense that other people could stand a chance of pulling you out of it — if you don’t put yourself out there to try to pull other people out of whatever that might be on their behalf, it’s very difficult to find a reason not to check out.”

Gerard’s words made me reflect on my own encounter with him.

Being curious enough to take the steps to reach out and ask questions led me to one of the most insightful conversations I’ve ever had, and a chance at a connection with a new friend.

Ironically, I had never actually heard Gerard play in person before this interview; I’d only heard of him. Maybe that made me more curious, but now I know where and when I can find him!

A lot can be said about the importance of human connection and the unfortunate lack thereof nowadays. Gerard’s philosophy of life is something we can all take from, and speaking to him, it was clear how deeply he believes in what he says, and how intentionally he lives by it.

His music isn’t a performance so much as an invitation to pause and feel less alone for a moment. And in a place where thousands of students cross paths without ever meeting, that kind of presence is its own form of connection. The ukulele may be a simple instrument, but the community Gerard has created is anything but small.

So next time you see the Ukulele Guy — or Stéphane Gerard, as we know now — make sure to give him a smile or wave. Maybe even start a conversation or join in for a song!

Merci pour tout, Stéphane!

Leave a Reply