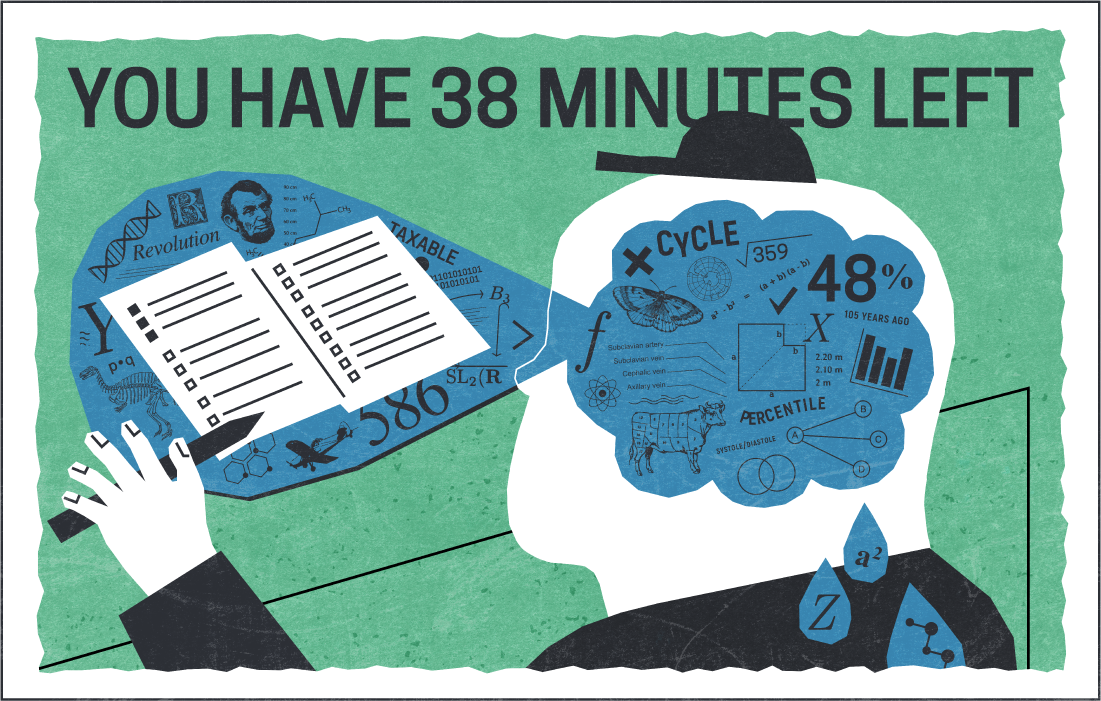

We’ve all experienced the worry that comes with writing an exam worth half our grade, with limited time, in a room full of hundreds of other students — or having a similar, stressful experience online.

It can be difficult to recall information and answer questions when the stakes are so incredibly high, and the stress means that many students may understand the subject material more than their grade would suggest.

Why? Because exams mostly measure our test-taking ability — how we deal with performance anxiety —- and not intelligence. That’s why it’s time to re-evaluate how learning in higher education is measured.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, universities have been forced to change how they assess students, and some of my professors have opted to ditch traditional exams altogether due to concerns of academic misconduct. However, in some of my classes, exams were made harder by greatly reducing the allotted exam time to mitigate cheating.

In theory, it seems quite practical — simply reduce the time of an exam to give students less time to look up answers in their notes or online. In reality, however, reducing the time for the exam also reduces the time for academically honest students to think critically about each question before answering.

Despite the measures implemented for online exams that are meant to uphold academic integrity, such as prohibiting backtracking on exams questions — the act of preventing students from revisiting previously unanswered questions — many students have learned new ways to cheat during the pandemic.

Websites like Course Hero and Chegg, which are marketed to provide homework help for students, have seen an increase in the number of questions and answers posted. Many universities across the country are concerned that students are actually using such services to cheat by inappropriately sharing answers to exam questions. Even with measures such as limited exam times, it is not impossible to access these websites during an exam.

In fact, from July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020, the University of Saskatchewan found 82 students guilty of academic misconduct, compared to only 45 the year before— an increase likely due to the switch to remote learning, which took place in March, 2020. Of these students, 49 were caught using commercial websites such as Chegg to complete exams or assignments.

In my opinion, cheating is more common now, not because it has become easier to get away with it during the pandemic, but because remote learning is much more difficult for students, and cheating can be the easiest way out.

In no way do I condone cheating, but despite the severe penalties for academic misconduct, it is no wonder that many students are willing to sacrifice it all for an A+ when the education system places such a high value on good grades.

Over the years I’ve been at university, it seems that education has become more about acing exams and outscoring your classmates than about learning. That’s because achieving good grades has become grossly synonymous with intelligence, and with a busy schedule and limited time to study between classes, simply memorizing subject material has become easier for students than actually learning it.

As a biomedical science student, a relevant example would be studying something as complex as the metabolic pathways. It has become a running joke among my classmates and I that no matter how many times we learn the Krebs cycle, we will never actually remember it after the exam is finished.

Sorry to any of my past professors who may be reading this, but many of us students only study to memorize things until we no longer need to remember them.

Excelling on an exam, then, is not an indication of what a student has learned, but rather what a student remembers at that moment in time. And what’s more, is that everyone learns at a different pace — so is it fair to require that students write an exam before they are even ready?

That’s why exams should be given a smaller role in benchmarking students’ success. If there is one thing that remote learning has shown, it’s that other forms of assessment that require a greater understanding of subject material, such as writing essays or giving oral presentations, foster learning and engagement more than traditional exams ever could.

I think it’s time universities do away with heavily weighted exams to measure learning in favour of assessments that test more than just a student’s memory and their ability to write an exam.

—

This op-ed was written by a University of Saskatchewan undergraduate student and reflects the views and opinions of the writer. If you would like to write a reply, please email opinions@thesheaf.com. Jakob is a third-year undergraduate student studying physiology and pharmacology, and the staff writer at The Sheaf Publishing Society.

Graphic: Jaymie Stachyruk | Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply