After much delay, the WHO officially declared the outbreak of the novel coronavirus a pandemic on March 11. This isn’t the first pandemic and it won’t be our last, so it begs the question — can epidemics of the past help us to navigate diseases of the present?

There are 727 cases* across Canada with Saskatchewan announcing its first case on March 12. The United States has identified 9,345* and now ranks sixth out of the 155* affected countries. We are both seeing a steady rise in more cases.

There are no antivirals available to treat COVID-19, and we have no vaccine ready to protect us against the virus. This means we have to approach this pandemic differently in the absence of treatments. How do our strategies to contain the virus emulate those of our past?

Erika Dyck is a professor of history at the University of Saskatchewan and the Canada Research Chair in the History of Medicine. She sat down with the Sheaf to talk about what history has to teach us.

“It’s really interesting teaching medical history right now in the midst of this pandemic,” Dyck said. “It’s interesting to watch students grapple with the historical knowledge that these things have happened before and we know there are certain measures for prevention.”

Fear is common

Some people are beginning to panic with the spread of COVID-19. This anxiety is manifesting in strange ways with toilet paper shortages and mass mask purchasing.

Dyck points out that what is part of the narrative today is common in historical pandemics.

“Some of the things we know for sure is that there is fear, panic, skepticism and a kind of mystery of what to do in these moments,” Dyck said. “What is your best strategy? Is it to go out and close borders or is it to wash your hands? We start to think about how to govern in a moment of panic.”

Wash your hands

Hand washing isn’t an innovative strategy for disease control and there is a long history of people not convinced by its effectiveness.

In the 1840s, Ignaz Semmelweis was deeply troubled by the number of women who were dying of childbed fever in his Viennese hospital. After investigating the difference in mortality rates between physician-run obstetrics units and the ones run by midwives, Semmelweis realized the doctors must be the source of this fever.

At the time, physicians would go directly from autopsies to a labouring women’s bedside without washing their hands in between. Semmelweis recommended hand washing after handling a corpse and it demonstrated a sharp decrease in women’s deaths after doctors in his ward followed his recommendations

But not all physicians were convinced and many were offended that Semmelweis was suggesting they were diseased. Today we are championing hand washing more than ever as a way to mitigate the spread of illness, yet we are still having to convince people that washing their hands is effective.

Flatten the curve

Social distancing is the buzzword that is circulating right now. We have seen cancellations of events, schools and other public gatherings.

The rationale behind limiting contact with people is not to stop the spread of the virus — we are past containment strategies — but to slow down how many people will be getting sick at once.

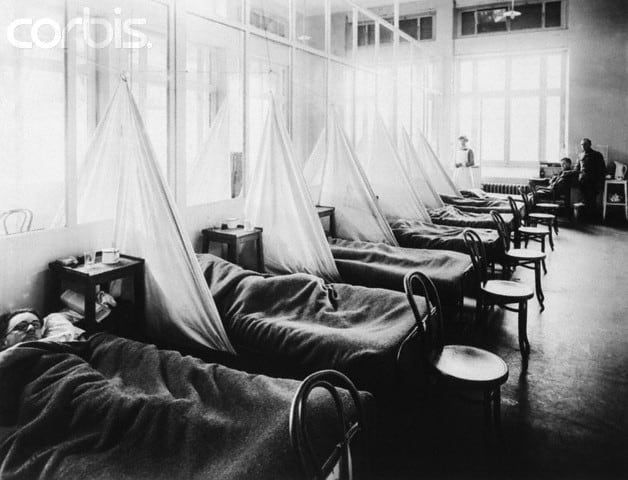

This strategy is called “flattening the curve” and is a lesson from the response to the 1918 Spanish Influenza outbreak. At the end of September 1918, the city of Philadelphia held the Liberty Loan parade as a way to entice people to support the war. However, this mass of people gathering in the street had dire consequences.

In just 72 hours, influenza burned through the city, leading to an influx of patients filling Philadelphia hospitals. In October, the city saw 759 people die in a single day with 12,000 succumbing to the flu in the next couple weeks.

This event is an example for why cancelling events and limiting social contact is important. It helps to curtail the number of people that get sick at once which lessens the burden on health care systems.

“We are really seeing people mobilizing around the questions of prevention — things are being cancelled and classes are moving online across North America,” Dyck said. “I think we are going to feel the impact. People are being forced and compelled to mobilize in ways we probably have not felt in our lifetime”

Societies change in the face of pandemics

The way that we respond to the challenges faced in pandemics is critical. Historically, these event often lead to significant changes in how our society operates. Dyck suggests that epidemics like these force us to think about how we invest in our societies and our health care systems.

Dyck has been working with Simonne Horwitz, a fellow history professor, and Scott Napper, a professor from the College of Medicine and research scientist at Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization – International Vaccine Center, to develop a new course on the history of infectious disease and vaccines.

“We think this is incredibly important,” Dyck said. “It is not just taking stock of things that happened in the past, but really thinking about how historical thinking and perspectives help to inform our contemporary understanding of how to handle these crises.”

* All numbers are taken from the John Hopkins University and Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center and Map, on March 18

This op-ed was written by a University of Saskatchewan undergraduate student and reflects the views and opinions of the writer. If you would like to write a rebuttal, please email opinions@thesheaf.com.

—

Erin Matthews | Opinions Editor

Photos: JohnnyJohnsonSOU / Flickr, NSW State Archives / Flickr

Leave a Reply