On Jan. 16, numerous news outlets, including the New York Times, reported that Monica Crowley, chosen by President Donald Trump to serve on his National Security Council, will not be accepting the appointment following two recent allegations of plagiarism. Soon after a review conducted by CNN KFile found over 50 instances of plagiarism in Crowley’s 2012 bestseller, What the (Bleep) Just Happened?, Politico revealed that she had plagiarized substantial sections of her 2000 PhD dissertation.

Clearly, acts of plagiarism committed by individuals in the past can come back to haunt them. Since the 2002-03 academic year, when the University of Saskatchewan began to collect data on academic misconduct, 758 allegations have been made across all colleges. Plagiarism is by far the most common form of academic misconduct, comprising 50 per cent of allegations brought forward since 2009.

Susan Bens, educational development specialist at the Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching Effectiveness, explains that there are many common reasons students plagiarize.

“That last minute panic, feeling like the assignment isn’t relevant, feeling like other students are cheating and that it would be crazy not to take those steps … not  really knowing the rules, not knowing how to reference or when they’re allowed to collaborate with other students and when they’re not, what’s the difference between someone proofreading my assignment and someone editing it in a way that would be a problem. So that kind of not clear on the rules and then not clear on how to follow the rules,” Bens said.

really knowing the rules, not knowing how to reference or when they’re allowed to collaborate with other students and when they’re not, what’s the difference between someone proofreading my assignment and someone editing it in a way that would be a problem. So that kind of not clear on the rules and then not clear on how to follow the rules,” Bens said.

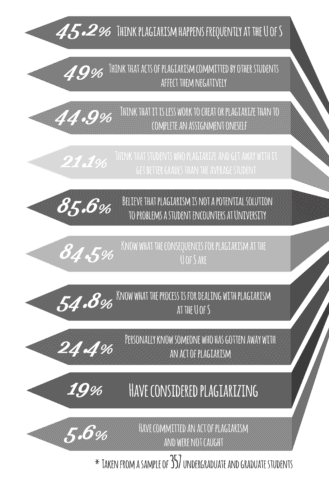

An online plagiarism poll conducted by the Sheaf in January 2017, which received responses from 357 graduate and undergraduate students, found that 9.2 per cent of respondents have committed an act of plagiarism. Of these respondents, the top five most common reasons for plagiarizing were anxiety and stress, demanding schedule or workload, fear of failure, lack of interest in assignment and ignorance.

When asked how they got away with plagiarism, one anonymous respondent answered that they believe small cases of plagiarism happen on a regular basis.

“It was just a little thing, like copying an assignment from another student when I ran out of time to do it. I didn’t copy it word for word; I would change answers a bit. I would say almost every student has done that at some point or another in their university career,” the respondent said.

Brent Nelson, head of the English department, frequently finds cases of plagiarism, especially in his first year classes. Although 44.9 per cent of Sheaf poll respondents believe that it is less work to cheat or plagiarize on an assignment than it is to complete it oneself, Nelson explains that the opposite is true.

“Usually plagiarists grab the easy stuff because they are desperate, running out of time. If you have the time to be a good plagiarist, you have the time to be a good writer,” Nelson said. “To be a good plagiarist, to get away with it, you have to put in the work.”

Nelson feels that plagiarism damages equality and fairness among students. Agreeing with Nelson, Elana Geller, peer assisted learning co-ordinator of Student Learning Services, also believes that plagiarism is detrimental to the integrity of an academic community as a whole.

“If what we want to have is an academically robust conversation … we expect that conversation to be honest and we expect people who partake in that conversation to be honest,” Geller said. “One of the things that can harm people is that if you don’t know who those honest people are, you don’t know if some of the data that you’re relying on or if some of the past things that have been written [are] accurate.”

To help combat plagiarism more effectively, university council approved new student academic misconduct regulations in June 2016 after extensive revisions, regulations that came into effect on Jan. 1, 2017. The Office of the University Secretary has also produced a brand new flowchart to lead students and instructors through the allegation and appeal processes, a resource which can be found on the university website.

University secretary Beth Williamson explains that students facing allegations of plagiarism usually speak to their professors first and potentially sign off on an informal resolution. If no informal resolution is agreed upon or available, the case proceeds to a college-level hearing and a sanction is decided upon, after which students have 30 days to submit an appeal if they so choose. If the appeal is granted, the student makes their case at a university-level hearing.

According to Williamson, the most significant change in the new regulations is the documentation of informal resolutions.

“[We are] now collecting copies of the informal sign off and in the future would also be able to identify if … it’s been multiple times where [a student has] been plagiarizing,” Williamson said. “The view is that if it’s multiple times, then the informal resolution is not going to be available to the student. It would have to go to a more formal hearing.”

Kyle Anderson, undergraduate chair in biochemistry, has served on the academic misconduct subcommittee at the College of Arts and Science for six years, and he explains the hearing process in more detail.

“Typically the instructor starts off presenting the allegation of plagiarism or other academic misconduct. The committee has a chance to ask any questions for detail to strengthen the case … the student gets their chance to say what their side is,” Anderson said. “After we’ve satisfied ourselves that we understand what happened in that specific case, the instructor and student leave and we ask two questions: is the student guilty or innocent? And if so, what’s the penalty that will be imposed on that student?”

Of the 758 allegations of academic misconduct since 2002, over 80 per cent of students were found guilty and received a sanction. While sanctions range from a  lowered or failing grade to expulsion, only 2.5 per cent of guilty students have been expelled from the U of S.

lowered or failing grade to expulsion, only 2.5 per cent of guilty students have been expelled from the U of S.

Gloria Brandon, director of student academic services at the College of Arts and Science, assures students that committing an act of plagiarism does not lead directly to expulsion.

“It’s amazing how many students think that because they got caught, whether it’s plagiarism or cheating, that they’re going to be expelled from the university. So I try and get in touch with them and sort of walk them through the process — ensure them that as a first offence, the penalty will be directed usually to the grade in the course,” Brandon said.

Along with formal consequences of plagiarism, professors include prevention strategies of in their courses, such as assignments with multiple components that build on each other. Lorin Elias, associate dean of student affairs for the College of Arts and Science, shares one common tactic he used as a psychology professor.

“One of my work-arounds as an instructor was to create a really unique assignment that people couldn’t just find a paper to download somewhere else and it was an assignment that kept updating itself every year, so I would rely heavily on popular media,” Elias said.

He also states that conversation has reopened at the College of Arts and Science concerning Turnitin.com, an online service that institutions can use to detect some forms of plagiarism, among other features. The U of S has decided not to use the service in the past due to ethical, financial and copyright concerns, although other Canadian institutions do, including the University of Regina.

Outside of professors’ preventative work, the university provides resources for students who are struggling with their assignments, such as the Writing Help Centre and the study skills workshops offered by the Learning Centre. Geller also explains that the Learning Centre is in the process of creating an online module program that will teach students about plagiarism and how to avoid it.

Brooke Malinoski, U of S Students’ Union vice-president academic affairs, is another resource for students seeking academic advice. She attends both college and university level hearings for academic misconduct, providing emotional support for and sometimes speaking on behalf of students.

In her first summer on the USSU, Malinoski received an unusually high number of grievances from students, which has led her to advocate for an ombudsperson on campus, a third-party personnel who could advise students on matters of university policy and administration. According to Malinoski, the U of S is the only U15 university without an ombudsperson or a student advocacy office.

“There’s a lot of stigma associated with academic appeals or accusations of academic misconduct … and there’s a lot of shame, so students don’t talk about it. So you don’t know who this has happened to or you haven’t heard about this happening to your friends,” Malinoski said. “I think students really need to ask themselves that question of ‘where would I go if I found myself needing advice on academic policy,’ and I think you would quickly realize that, apart from the USSU … you really wouldn’t know.”

In the Sheaf plagiarism poll, respondents believed that the most important support source for students who are considering plagiarism is an approachable professor. If Bens were speaking to a student in this position, she would encourage them to seek out resources and to talk to their professors, rather than make a wrong choice.

“I would say, don’t do it. I’d say, why are you considering taking a risk like this? Why are you considering short-changing yourself like this? What are your other options?” Bens said. “Because there are other options, including seeking an extension, submitting what you’ve got and learning for next time.”

—

Jessica Klaassen-Wright / News Editor

Graphics: Lesia Karalash / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply