The Number Five Platoon of the 196th Western Universities Battalion poses in front of the University Administration Building in 1916.

On June 28, 1914, the assassination of archduke Franz Ferdinand sparked a conflict that grew to become the First World War. Although combat took place in Europe, the effects of the war were felt in Canada and much closer to home, on the University of Saskatchewan campus.

Dedication of the Memorial Gates in 1928 to commemorate those who lost their lives in the First World War.

Ferdinand was the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and was killed by a young Bosnian nationalist. Up until that point, tension was building in Europe through an arms race, complex alliance systems and growing resentment with the balance of power between countries. Ferdinand’s assassination became the trigger for a war that lasted nearly four and a half years.

In 1914, Canada’s foreign affairs were under British control, so when Britain declared war on Germany on Aug. 4, Canada entered the war along with the rest of the British Empire.

The U of S’ contribution was a significant one, with a total of 345 students, faculty and staff who enlisted, most of whom did so voluntarily. Sixty-nine of these brave souls never returned, while 100 came home wounded. For a university that was only seven years old in 1914, these numbers made up approximately three-quarters of the campus population.

Within three months of the outbreak of the First World War, a recruiting program was initiated on campus. Benefits were given to those who enlisted; students who joined the ranks were given credit for one year of university, while staff and faculty were given half pay for enlisting. The university began military instruction and drill exercises for students and staff, which continued throughout the duration of the war.

The U of S president in 1914, Walter Murray, was a strong supporter of the war and promoted recruitment as an ideal of the Anglo-Saxon race fighting for the rights of the British Empire, in an attempt to urge students to go to war.

Keith Carlson, U of S professor of history and research chair in Aboriginal and community engaged history, speaks to the atmosphere on campus in 1914.

“One of the things that I think would strike a lot of students as unusual today, is that the president of the university and the faculty were just gung-ho trying to get students to enlist and go overseas and fight. So there was no pretence to stand back and let people make up their own minds, and there was no sense that someone would decide not to go fight. It was, ‘This is your duty and your opportunity,’” Carlson said.

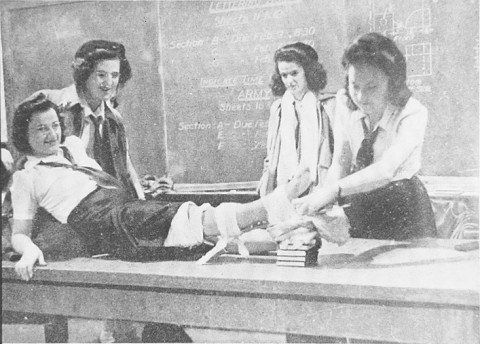

Female students participate in emergency war training in 1944, for the Second World War. Many women stayed on campus during the First World War and continued their studies.

The first recruits from the U of S went into the Canadian University Battalions, were trained at McGill University and were sent overseas as reinforcements for the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry. In 1916, the U of S was involved in the creation of the 196th Western Universities Battalion, which was a joint effort between the U of S, the University of Alberta, the University of British Columbia and the University of Manitoba, each of which provided a company of students to create the battalion.

The 196th Battalion was trained in Manitoba and then sent to England but did not end up fighting together as one unit, with many men being assigned to the 46th Battalion, which was primarily men from Saskatchewan.

Many initial recruits were voluntary but once conscription was introduced in 1917, 11 U of S students were drafted that year and 18 more were drafted in 1918.

U of S students, staff and faculty fought in the battles of Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele, Sanctuary Wood and Courcelette, among others. Many men from the U of S made their way up from private to lieutenant, making notable contrabutions to the war effort.

Female students generally remained on campus, aside from one student named Claire Rees, who volunteered to go overseas as a nurse. Many female students supported the war from home however, helping to recruit or sending parcels and goods to their male counterparts. Women’s role on campus also increased, along with their responsibilities, especially in terms of academic instruction.

The loss of male professors offered an opportunity for women to step in and teach. In one case, the only English professor in 1914, Reginald Bateman, enlisted and left his classes behind.

Louis Reed-Wood, fourth-year history student and employee of the Diefenbaker Canada Centre, speaks to the impact of the loss of instructors.

“A lot of people were not happy that [Bateman] left teaching mid-term. They’re like, ‘We paid our tuition and now we have no English professor,’ because there’s no one; I mean the university’s so small at that point that there isn’t a second English professor,” Reed-Wood said. “One of the things that comes out that’s interesting is you see a massive jump in the number of female instructors, because a lot of them were not professors beforehand, but they’re sort of scrambling for instructors.”

This change in the ratio of female to male students also allowed female students to have a say in what they studied. One history professor who was too old to fight, Arthur Morton, found himself in an interesting situation once male students were gone.

“Morton suddenly had all these female students, so he starts a history club. It was all female students and if you look at early issues of the Sheaf, it talks about some of the projects that female students were doing. They were doing women’s biographies and bringing their own interests,” Carlson said.

“I think that must in some ways, [have] given those young, female students a sense of power and agency in a way. There weren’t male students pushing them out of the way. It would of been hard for them when after the war, all of these male students came back.”

While school picked up for the women, studies didn’t necessarily stop for males either. Edmund Henry Oliver was a U of S history and economics professor, and also the principal of St. Andrew’s College on campus. He enlisted in 1916 as the chaplain for the 196th Western Universities Battalion, but while overseas, he realized many men were bored spending hours waiting in the trenches or between battles.

Oliver created what was called “Vimy Ridge University,” which was a way for students to continue their education while also being involved in the war.

“This was the very first academic intellectual unit in the Canadian military and it was so popular that the British went on and adopted the same model for the entire British army. And it was a U of S professor who said, ‘Hey, these guys should be reading classical liberal art works, they should be learning basic sciences and they should be learning applied technologies.’ These are things that are going to make them better soldiers potentially, and better citizens when they come back,” Carlson said.

Reed-Wood echoes these sentiments, speaking to the popularity of this model.

“What they end up doing with Vimy Ridge University is they end up offering courses abroad — now not all of these are for credit, but in general, they’re actually quite popular and there’s actually a lot of people who turned up to the lectures,” he said.

Vimy Ridge University continued during 1917 and 1918, until the Germans initiated a big offensive attack in the spring of 1918 and men were needed at the front.

Not all colleges and programs were able to support themselves on campus however, and from 1916-17, the College of Engineering completely shut down due to a lack of students and faculty. Some students and faculty also left their studies to go home to farms to support the war, through research and agriculture.

“One of the big things, the big pushes, especially in Saskatchewan, is that Canada was seen as a place that the allies could draw upon natural resources, whether that be wheat, timber, whatever. So Saskatchewan has this big part in producing food for the armies,” Reed-Wood said. “And so, agriculture students, you see a lot of them take time out of school to go back to their farms to produce food.”

President Murray was also a supporter of agricultural research and in late 1916, he joined the Honorary Advisory Council for Scientific and Industrial Research to direct research in areas that were beneficial to the war effort.

One such issue was a crop disease called “wheat rust” that was affecting cereal plants and grains in the prairie provinces, causing a blow to the food needed to feed the allied war effort. The U of S was involved in such research, seeing as Saskatchewan was a valued importer of food during the war.

Regardless of the variation in student, staff and faculty contributions, the war brought a lot of transformation to the campus. According to Carlson, the war meant some major changes for the student experience.

—

Naomi Zurevinski / Editor-in-Chief

Photos:

Number Five Platoon: U of S, University Archives & Special Collections, Photograph Collection, A-1130

Memorial Gates: U of S, University Archives & Special Collections, Photograph Collection, A-532

Female students: U of S, University Archives & Special Collections, Photograph Collection, A-6410

Reginald Bateman: U of S, University Archives & Special Collections, Photograph Collection, A-3157

Walter Murray: U of S, University Archives & Special Collections, Photograph Collection, A-5559

Leave a Reply