“It’s not about us or them. It’s about giving human dignity where it belongs—with humans.”

In the two decades since September 11, 2001, stories have shaped how the West understands fear, violence and who belongs. Novels, films, news media and television have all tried to make sense of national trauma. In doing so, however, they have often relied on familiar, problematic characters and narratives to explain it.

Among the most persistent of these is the figure of the Muslim: the symbol of danger, suspicion or cultural incompatibility. Even as the media claims to be more progressive than it was in the early 2000s, many of these portrayals remain strikingly unchanged. To understand why, it helps to look beyond individual stories and towards the ideas that have long structured how the “other” is imagined in Western culture.

As Edward Said once explained, the “Orient” is an idea, a discourse. One that has long been constructed by writers, scholars and artists of the West as a narrative opponent, rather than a real place inhabited by real people. Irrational where the West is rational, uncivilized where the West is civilized, backwards where the West is progressive.

Despite what one might think, the tenets of Orientalism still live on in modern media, the only difference being their updated scripts.

In particular, Muslims are rarely allowed to exist in the media as anything other than a problem. These characters are warmongers, murderers and terrorists—villains whose violence is framed as cultural, rather than contextual. They emerge from distant, vaguely defined deserts, frozen in time — lost in perpetual chaos, ruled by fanaticism and fundamentally incompatible with the civility of the West. It is here where geography becomes a moral judgement, and distance its justification.

Modern media — despite its obvious progression from what it once was in the early 2000s — continues to reproduce this cyclical, racialized logic, constantly arguing that Muslims are symbols of timeless barbarism and not individuals acting within history. It argues that violence committed by Muslims is not an action, as it would be with any other group, but an inherent trait. When a Muslim character commits some vile act, its explanation becomes religion, culture or tradition—instead of the psychological, circumstantial or political explanations that would be given for the same acts committed by others.

Fiction now pretends to critique these ideas, while perpetuating them endlessly. Novels about war, spy thrillers or even literary fiction all rely on common imagery: dusty streets filled with faceless hordes. Muslim characters often remain nameless or interchangeable, their inner lives totally irrelevant to the plot. They exist to be feared, defeated or escaped.

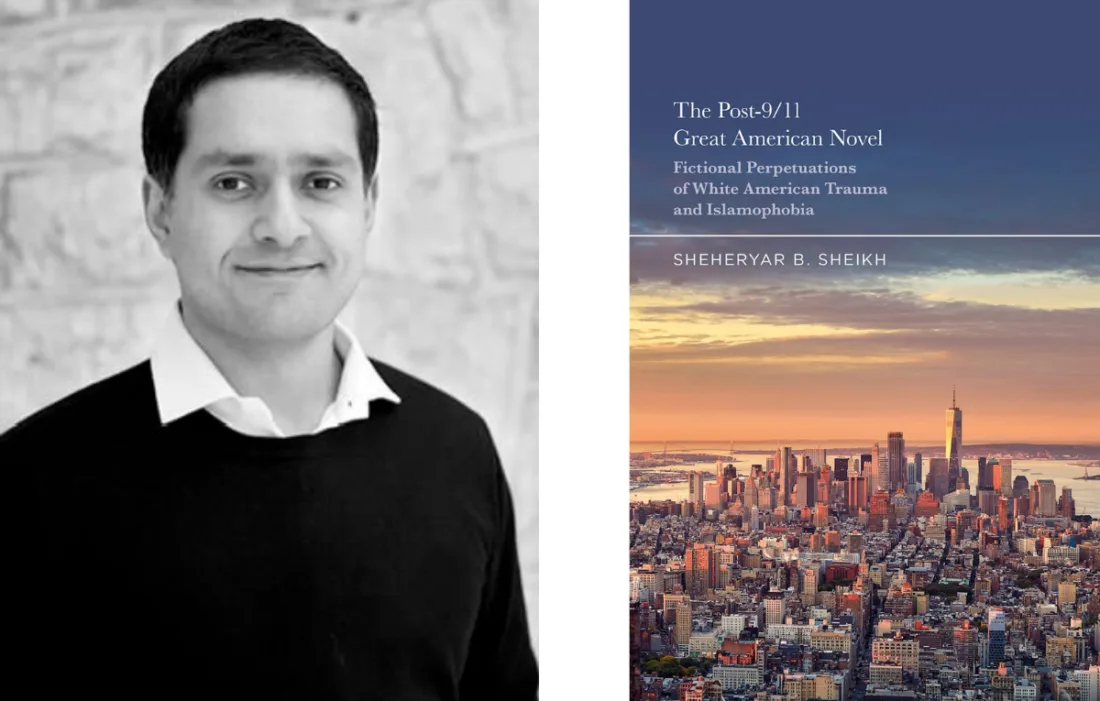

Sitting down with University of Saskatchewan alumnus Shehreyar Sheikh, who recently published his latest work The Post-9/11 Great American Novel, we discussed the construction of such narratives at length—and the ways literature, media and national myth-making have helped entrench fear, exclusion and islamophobia in popular culture.

Sheikh, now a post-doctoral fellow at Dalhousie University, earned an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Notre Dame and a PhD in English from the University of Saskatchewan, where he worked with English professor Lindsey M. Banco. For his dissertation, Sheikh won the University of Saskatchewan Doctoral Dissertation Award in the Fine Arts & Humanities category in 2024. It is from that dissertation that Sheikh’s latest work was born.

Sheikh took a short break from academia after he earned his Master’s degree, working in New York and London for five years before he decided to go back to writing. He travelled back to Pakistan, where he taught at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, writing novels on the side. As time wore on, writing once again became compelling.

“I started working on another novel, my fifth practice novel, … and I thought I should get a PhD and get a stipend to get more writing time for myself. So I literally applied for a PhD, thinking, ‘Let’s get writing novels.’”

In the first four years of his doctoral program, Sheikh was able to write two novels and get them published. “I was very happy with that,” he says, “but then I realized, ‘Oh, I have to finish the PhD as well.’”

When asked what inspired him to investigate post-9/11 American literature and islamophobia, he explains that his long-standing fascination with apocalyptic literature naturally evolved into a focus on apocalypse theory, and from there his ultimate topic became clear.

“I’ve always been interested in apocalyptic writing and apocalyptic events—how societies imagine endings. I had been writing essays on apocalypse theory across different classes, so I went to my supervisor with this ambitious idea: I wanted to write a dissertation that covered novels, films, video games and develop a new theory of apocalypse.”

“My supervisor listened and then said, very calmly, ‘This is probably a twenty-year project. You’re not going to finish this in the two-to-four-year PhD timeline. He advised me to narrow it down to a specific apocalyptic event — something that affected me personally, emotionally and intellectually. That’s when 9/11 became the obvious focus.”

When the attacks happened on September 11, 2001, Sheikh was a student at Franklin & Marshall College in Pennsylvania. He recalls going to his older brother’s room and watching the second plane hit the World Trade Center on TV.

“I spent the rest of the day glued to the news, terrified — not only of the violence itself, but of going outside on a mostly white campus, and of what would happen if Muslims or Pakistanis were involved. I remember hoping, very irrationally, that no Muslims were responsible. That hope disappeared very quickly. Over the following years, the United States launched the War on Terror, invaded Iraq and began drone strikes in Pakistan.”

At the same time, Sheikh was becoming more critically aware of American literary traditions, particularly the idea of the ‘Great American Novel.’ The concept, dating back to 1868, was originally imagined as a way to narrate national unity in literature, following the Civil War. He explains that the ‘Great American Novel’ always re-emerged in the zeitgeist after moments of crisis, such as World War II, the Vietnam War and again, after 9/11.

“What it was meant to do was narrate the unification of America using novels already written and future novels as well, asking writers to write within an American novel tradition of uniting the nation. ‘What is America? What is the American spirit?’ This American theme or teleology was frequently used afterward in phrases like the American Dream, Manifest Destiny and all those things — very American-centric ideas.”

He points to novels like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces as works that revealed the true nature of the American dream.

“The Great Gatsby very much shows how hollow the American Dream can be. Characters such as Gatsby pursue merit-based, wealth-based notions of achievement, and that produces everything in the middle — even the one objective he had of winning the love of his life back, which he doesn’t achieve. And then there’s this beautiful novel, which I’m going to go into a little bit more, A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole, which directly in its scale addresses the dream and shows how hollow the American Dream is because wealth is hollow as an end product to aim for.”

He explains that, within the academic world, the term “Great American Novel” fluctuated in popularity. “It lost currency after World War II, came back in the 1970s after the counterculture, then again with Toni Morrison’s Beloved and then declined again in the 1990s. After 9/11, Don DeLillo wrote an essay in The Atlantic called ‘In the Ruins of the Future,’ in which he called for a ‘taking back’ of the narrative from the terrorists. I saw this as a renewed call similar to William Dean Howells’s call for the Great American Novel. So the writers I examine are writing nation-building texts in the post-9/11 moment, using tropes like innocence, trauma, meritocracy and exclusion — often reproducing hierarchies even as they critique them.”

He expanded. “But after 9/11, the term didn’t exactly come into vogue again. But Don DeLillo, whose novels are cited as some of the great novels of the twentieth century, wrote an article in The Atlantic called “In the Ruins of the Future” in December 2001. So the writers writing in the post-9/11 moment that I’ve examined have all been writing in the Great American Novel tradition — trying to create nation-building texts using tropes such as the innocent child thrust into big political discussions they don’t understand, but receive nonetheless, like Huckleberry Finn.”

Sheikh points to Amy Waldman’s The Submission as a clear example, where the promise of meritocracy collapses in the face of entrenched hierarchies. As with Gatsby, he says, the novel’s central figure ultimately fails not because of personal shortcomings, but because the system itself excludes him.

“You see this in Amy Waldman’s The Submission, where a Muslim wins a blind competition to design the 9/11 memorial. But again, this plays into The Great Gatsby. Gatsby does not win everything. Similarly, Mohammad Khan in The Submission is not able to have his memorial built simply because he is Muslim. He is the outsider. There is a hierarchy built into the system.”

Sheikh describes his work as an attempt to bring these post-9/11 novels into conversation with the longer history of the Great American Novel. “I see my study of the Great American Novel tradition as a new way to approach post-9/11 novels. That’s my intervention into the scholarship.”

He was critically aware of the concept before his PhD, even attempting to write a Pakistani-American immigrant novel himself, knowing that as a Pakistani writer, he could only ever produce a hybrid version.

“In my manuscript titled Americans, imaginatively, I attempted to create a metafiction that breaks boundaries between nonfiction and fiction, manipulating footnotes and other spaces and varying fonts, thereby playing into what Kevin Hayes calls the ‘Great American Novel tradition of inventing a form-destroying story.’”

More recently, while combining postcolonial studies and research on 9/11 novels at the University of Saskatchewan, Sheikh published a creative-critical hybrid essay that explored the pared-down language and signifiers in Cormac McCarthy’s seminal post-9/11 novel The Road.

“In the two decades since the terrorist attacks, I have deeply engaged with and sought to analyze the ways in which the trauma of white Americans has influenced the lives of Middle Eastern-looking Muslims in the United States. I now find it reasonable to assume that there have been direct and indirect ramifications of 9/11 on the trajectory of my professional and personal life while living within an American state.”

He expanded on this. “The focus of my research for this book, therefore, is on the terrorist state’s immediate and short-term aberrations, and it teaches my interventions with which I not only contribute to scholarship in this field, but also understand the influences on my life as a Muslim scholar and producer of literature in North America.”

Sheikh believes there are several reasons to study early post-9/11 literature in isolation, and one of them is to examine the Western reflex to always believe the West is at the incipient stage of the Other — Islam and Muslims.

“The reorientation toward Islamic ideology as a clash came more directly into focus right after 9/11, especially as it was an attack on Western symbols of progress and capitalist power at the cusp of what was supposed to be a new millennium, promising unfettered progress once the internet’s true potential was realized.”

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 were framed as a world-altering rupture, a moment that divided history into ‘before’ and ‘after’ and sustained a permanent sense of crisis. In the process, Western societies once again turned away from their idealized self-image and redirected fear towards Muslims, treating Islam as a sudden and foreign threat — as if Muslims and Islam had just appeared out of the ether at that moment.

When asked what he hopes readers take away about American self-mythology after 9/11, Sheikh explains that he hopes to examine the mobilization of fear and the use of adversarial othering to perpetuate endless cycles of oppression.

“The self-mythology of any nation is riddled with disgusting cover-ups of atrocities. Walter Benjamin says there is no object of civilization created without acts of barbarity buried underneath it. I’m paraphrasing, but that’s the gist. America is papered over genocide. It’s papered over inequality. It calls itself the greatest nation — this BS that keeps lasting. And similarly, Canada — even the Canadian state — is reflecting a little bit upon itself about genocide, reflecting a little bit through the reconciliation commissions. But of course, not changing any policy based on that — just a little bit of uncovering at a time, and a horror show of what it’s done, just as it peeks into it.”

With the self-mythology of the U.S., there is a constant balance between a generalized ‘us’ and ‘them.’ A perpetual adversarial othering of any and all minority groups within the population.

“America doesn’t even allow that reflection. It keeps papering over inequality and oppression caused by the one percent, using othering as a distraction. And it’s not just Muslims being othered.” He explains, “If I added another chapter to this book, it would be about how islamophobia is not the central concern of my scholarship. It’s an important facet in understanding how othering works.”

“… the majority are being brainwashed into thinking Muslims, Chinese, Black people are replacing them. Their education has suffered so much that critical thinking is gone. The ‘great replacement theory’ mobilizes fear. And that’s my objective — to examine how this works.”

At its core, Sheikh explains, the book is not only about Muslims but about the mechanics of othering itself. “It’s the other. To examine the othering of Muslims in detail and thereby examine what othering does.”

This process, he stresses, is universal and recursive — enacted by all societies against different targets. The ethical task, then, is not to invert hierarchies but dismantle them.

“I hope readers see the hollowness of what is being thrust down our throats. Mainstream American culture is hollow. It’s rapid, empty and when you reach the end of it, it shoots you in the face. But unfortunately, American culture surrounds us completely. The algorithm has us online and offline. We have to opt out deliberately — consciously — seeking sources outside the mainstream. It takes energy, but it’s worth it.”

Sheikh explains that the use of adversarial othering against Muslims — islamophobic narratives within media and fiction—did not start with the September 11 attacks. They had been present since earlier in the twentieth century, when Arabs and Eastern Europeans became the common figures of evil within cinema. He recalls watching movies like True Lies and Taken, and being totally appalled by the paradoxical portrayal of Middle Eastern people.

“I remember watching True Lies and thinking, what is this nonsense of just going at somebody in a garb and making them completely brainless, but at the same time an evil mastermind. Similarly, in the Liam Neeson movie [Taken], the mastermind and kidnapper is Arab. It plays into the trope of the Arab [as] the mindless other. But at the same time, he’s carrying out this technologically, ridiculously, insanely perfect plan against the United States. It makes no logical sense, but it makes emotional sense for hating the Muslim other.”

When asked about the pervasive framing of Muslims as a faceless threat, Sheikh places islamophobia within a broader logic of dehumanization — one that depends on transforming entire populations into abstracted masses rather than individuals.

“So together, it’s like being dehumanized, being brought up as a zombie horde. And that’s ridiculous. The impulse to think of Muslims as a horde, whereas there are two billion of them, plus that, and not all of them are Muslims, but have been categorized as potential terrorists.”

The process of abstraction, he argues, is not merely rhetorical but materially dangerous. Once a group is stripped of their humanity, violence against them becomes not only permissible, but rationalized.

“And therefore, you can also perpetrate crimes against them because they’re so dehumanized — like the genocide that’s going on right now. You can do that easily because they’re not human. So that needs to be countered with being able to see the other as the self.”

Sheikh identified several mechanisms and several theories in his research that white American characters used to cope with trauma, like repression, appropriation, adversarial othering and enforced secularization.

He found repression to be most revealing, describing it as an always-present force.

“It’s a mechanism like — you try to shove the thing back in the box. Repression is there. So, like, not confronting Muslims, not confronting 9-11, not confronting the terror landscape of the buildings falling down. Not confronting that is like the reflex reaction to any kind of trauma — not wanting that to hit your face, right? So repression never goes away.”

He continued. “I understood that because theory says that the more secular a society is, this can happen either as cause or effect. The more progressive a society is, the more progress it makes technologically as well as sociologically, the more secular it will become. That’s the theory. But there is no true secular society in the world, because they begin to believe in some system, some form of ideology, like the scientific method — even as an ideology. But America is completely riddled with Christian symbols and Christian ideology. It pretends to be a secular place, but it’s not, obviously. Similarly with Canada.”

Sheikh resists a simplistic historical rupture when we approach the question of whether 9/11 is the origin of mainstream media’s tendency to frame Muslims as suspects rather than citizens or victims. While acknowledging the attack’s psychological impact, he emphasizes that islamophobia has deeper roots in American political consciousness.

“It’s not just Muslim. It’s not just the attack. As you were saying, there’s this underlying mistrust of Muslims that has always been there in the psyche of America. Not always, but [especially] from the 1980s onwards, [with] the Iraq War and other [events]. It has definitely intensified the spectre of the Muslim.”

For Sheikh, post-9/11 islamophobia is inseparable from unprocessed national trauma. The collapse of the towers remains symbolically unresolved, producing a compulsive need to displace fear rather than confront its political causes.

We are still living in the post-9/11 moment, despite the decades passed. The tower is still falling.

“Islam in America after 9/11 brings up the trauma of the unprocessed trauma of 9/11, because the buildings falling is not something you can confront, and it’s not been dealt with.”

He is critical of what he sees as a constrained discourse that asks Muslims to defensively disavow terrorism rather than engage in meaningful structural critique.

“Mostly, I find, unfortunately, the responses are Muslims coming into the center and saying, ‘Look, I’m not a terrorist.’ But that’s not enough of a response. It’s not conducive to the true production of discourse … what needs to be done is to show the world the political situation, the political ramifications of 9/11, the effects as they are.”

Sheikh rejects narratives that frame the aftermath of 9/11 as beneficial to American power, instead describing a global unravelling fueled by militarization, fear and intellectual laziness.

“It’s not Americans who benefit. It’s not the American state that benefited. It’s ruining the world. It’s actually ruining the world.”

When the conversation turns to contemporary islamophobia and anti-immigrant rhetoric, Sheikh identifies political utility as a driving force. Fear, he argues, is not incidental but instrumentalized.

Islamophobia, in this sense, is not unique but part of a recurring historical pattern of fear that was previously directed at communists, Chinese communities and other perceived threats throughout the ages.

“The anti-Islamic thing is actually more interesting because that’s the tool that has been used against communists in the past, against the Chinese.”

With the rise in anti-immigrant sentiment and global conservatism, Sheikh discusses the ways fear has been deliberately amplified and weaponized, transforming immigrants into convenient symbols for broader anxieties about economic decline, cultural change and political disillusionment.

He challenges the selective invocation of “Western values,” arguing that principles like equality and human dignity are not culturally exclusive — and are, in fact, routinely violated by the states that claim to uphold them.

“So-called American values, so-called Canadian values, so-called Western values … are actually the same values Muslims live by.”

Throughout his work, Sheikh draws heavily on a wide range of theoretical frameworks, from Edward Said’s Orientalism to trauma theory with Julia Kristeva and Freud, to theories of appropriation, secularization, adversarial othering, repression and political philosophy, situating his analysis within a long intellectual lineage including Oria, Agamben, Althusser and Foucault (who he once wrote a song about).

“I’m indebted to these scholars. I’ve stood on the shoulders of giants and loved it. The view from up there is transcendent. It’s beautiful.”

Reflecting on his research, Sheikh says he was surprised by moments of nuance within novels that nonetheless participate in islamophobic representation — texts that both reproduce and critique fear simultaneously.

“Even as they’re perpetuating the representation of white people’s trauma and white people’s islamophobia, they’re also critiquing it in many ways.”

Reflecting on the limits of contemporary public debate, he emphasizes the dangers of reducing complex human experiences to viral shorthand.

“We cannot deal with certain things superficially. The meme is the opposite of discourse, and we’re dealing with people not as memes, but as holders of discourse that might be valuable for ourselves as well.”

Ultimately, Sheikh’s hope for the future is grounded less in institutions and more in community: small, thinking groups of individuals committed to equality, dialogue and material justice. Rather than placing faith in states or abstract political systems, he emphasizes the importance of collective responsibility, sustained conversations and shared action aimed at economic equality and human dignity. For Sheikh, meaningful change begins with communities willing to care for one another, think for themselves and resist the politics of fear and division.

“… I want there to be a community-based thinking, and that’s what I’m going to leave as my legacy, hopefully. Very local, very community-based, positive action people. And I don’t believe in states. I don’t believe in countries. I don’t believe that there should be countries. I don’t believe that there should be borders.”

Expanding on this, he explained that he preferred to approach community issues through open debate that is geared towards the objective of equality. “I am very much of a Glorianza line of thinking, where borderlands are just arbitrary, completely arbitrary things, and there should be no borders. So communities — even if they are online, offline, local — not necessarily thinking the same way, but open to dialogue. But not in complete dialogue in terms of like very black and white subjects: “Is this a genocide or not?” That’s very black and white to me. There’s nothing nuanced about that.”

The conversation he hopes his book will spark is ambitious but specific: a reduction of fear, a rejection of dehumanization and a commitment to discourse over spectacle.

“Reduction of the other, reduction of fear of Muslims, to start with, maybe. But then an engagement with the idea that there is more to life than thinking about the other as a different entity to mobilize people into building these communities a little bit more.”

While he understood the realistic limitations of the work’s impact, Sheikh admitted that he hoped it would, at the very least, start conversations on the topic of critical media consumption.

“I mean, it’s a lot to ask for for one book, but I hope that a conversation starts about how mainstream media doesn’t need to be trusted. But also, these high culture productions are also producing some critiques that maybe are not as valuable as they should be. But to engage with the other absolutely, without a completely Linnaean approach like: “I’m going to wash the feet of the other to recognize him as myself.” Not that idealistic, heavenly, top-prophetic talk—we don’t need that. But we need to recognize other people as human beings, and to build communities, build conversations about difficult subjects with intellectual rigour. That’s important.”

Leave a Reply