Manuel Axel Strain, Kyle Beal and Anna Hawkins bring moving and impactful interpretations of Indigeneity, social presence and consumerism to USask galleries

On the evening of Jan. 13, artists Manuel Axel Strain, Kyle Beal and Anna Hawkins unveiled their new exhibitions on the USask campus — Strain with a solo exhibition titled Why does this land seem so small? and Hawkins and Beal with a collaborative exhibition titled day for night. Jake Moore, assistant professor and director of the university’s art galleries and collections, led the remarks for the exhibits which were followed by words from the artists and their family members.

Moore opened with a land acknowledgement and stated she “was a guest here [on this territory]. I cannot welcome everyone [here], but I can welcome you into this space and I can also accept responsibility for our operations as a colonial institution,” she continued, hinting towards the themes of each exhibit. “I’m excited to have you here today to witness a particularly rich engagement moving between historical methodologies and bringing forth different benefits of our thinking, intuition, relations and humour.” Moore then stepped away to allow Manuel Axel Strain’s family to introduce Strain on their behalf, as well as Leah Taylor, curator of both exhibitions, to discuss the artworks and exhibition space.

Manuel Axel Strain is a Two-Spirit interdisciplinary artist. On their website, they say that they are “from the lands and waters of the xʷməθkʷəyəm (Musqueam), Simpcw and Syilx peoples, based in the sacred region of their q̓ic̓əy̓ (Katzie) and qʼʷa:n̓ƛʼən̓ (Kwantlen) relatives.”

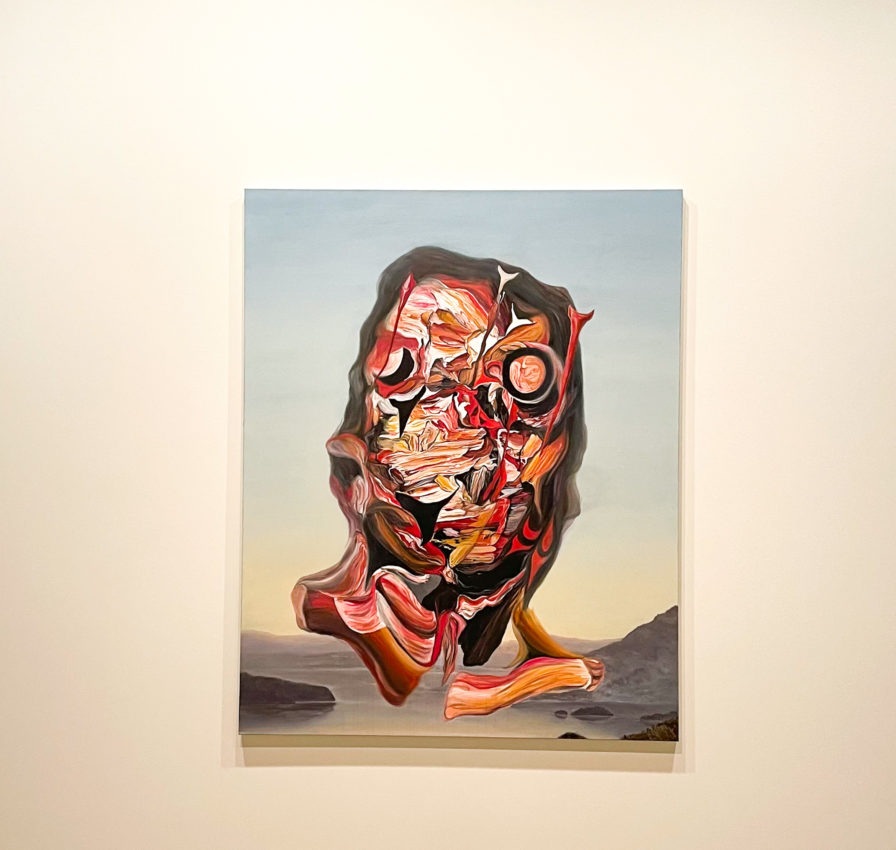

Strain creates artwork with heavy references to their ancestry. “Their shared experiences become a source of agency resonating through their interdisciplinary practice,” Taylor said. In Why does this land seem so small? Strain brings together their new and recent works with specific attention to the exploration of large-scale painting and sculptural installations.

Speaking about the exhibit, Taylor described how “Strain presents subjects enveloped in numerous forms of relation with ancestral and community ties; Indigeneity, labour, resource extraction, gender and Indigenous medicine and life forces being just some of the subject matter.” She went on to discuss how Strain “prioritize[s] Indigenous epistemologies through embodied knowledge of their mother, father, siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, grandparents and ancestors,” and invited traditional knowledge keeper and storyteller Lyndon Linklater, a relative to Strain, to highlight what he felt was important about the message of Strain’s art-pieces.

Linklater spoke on the themes of Strain’s exhibit and artwork, namely those of colonialism, paternalism and subjugation. He stated how the world today is changing in comparison to the past, and described our ideal world as a place where people can respect, value and love one another despite our differences. “They call it truth and reconciliation,” he said, “It’s a good thing. It’s a really good thing. And it’s up to us as Canadian people to learn the truth — the truth about our country to never make those same mistakes again and to create this better world that we all want to live in for ourselves, our children, our grandchildren.”

On the USask webpage dedicated to their exhibit, Strain’s work is described as being made to “confront and undermine the imposed realities of colonialism.” This work also reclaims space and history from the systems and powers of colonialism. It does this by combining colonial themes, Indigenous themes and visuals reminiscent of both histories into each of the artworks. Each of Strain’s painting and installation pieces in the exhibit work together to bring forth a powerful and emotional exhibition rooted in past and present familial connections.

Why does our land seem so small? is located at College Art Gallery 1 on the first floor of the Administration Building.

Kyle Beal and Anna Hawkins are two Alberta-based artists who collaborated on day for night, an exhibit dedicated to pointing out how modern technologies have blurred the lines between our public and private lives. Hawkins primarily works in moving-image (video) and installation art that “centres around the ways that images, gestures and language are circulated and transformed online, as well as the impact of technology on the intimate spheres of daily life.”

Meanwhile, Beal is a multidisciplinary artist who challenges convention through his conceptual art by incorporating a variety of media including drawing, sculpture and installation.

Hawkins and Beal’s respective practices share “conceptual considerations — questioning human relationships to screens, devices, 24/7 online existence, and effects these have on contemporary culture,” Taylor said, referring to day for night’s theme.

Hawkins’ piece at the exhibition, Blue Light Blue, utilizes visual effects, camera shots and colours that are typical of horror films, and casts a “blue light emitted by smartphones, laptops and tablets, and the threat that these have as they’re unwittingly invited into our most intimate spaces,” Taylor explained. Hawkins, adding onto Taylor’s introduction, explained her inspiration for the art-piece. “I was thinking a lot about devices and [how] our screens are not just a communicator — ways that we communicate, work, have experience, entertainment, really, most aspects of our lives are somehow mediated by screens, but also thinking of them as light-emitting devices […] I wanted to look more closely at how we perform or behave in that light.”

Carrying visual similarities to Hawkins’ piece, Beal’s installation, Business Class, consists of 24 illuminated neon ”Open” signs. Referring to his installation, the artist shared a story of its creation: “I found [the signs] on Amazon, which speaks to a certain amount of excess and oddness because they’re all unique, but within a very specific constraint, which I found interesting. They’re the same, but different, and we like to think of ourselves as individuals in that way too.”

Also displayed in the gallery’s backroom is Beal’s ongoing mirrored works series. “To engage with the work is to be interrupting it with your own reflection,” Beal said, referring to his glass artworks. Visitors to the gallery are likely to experience this exact phenomenon when stepping in front of the mirrors and interrupting the sparkling words across the glass surfaces with their own reflection.

One of the most effective attributes of Beal and Hawkins’ joint exhibition is how it casts a blinding blue light across the gallery space. The light envelops and immerses viewers into an environment that they may or may not already be eerily familiar with in their daily lives — that being an existence fully within the world of their technological devices.

day and night is located at College Art Gallery 2 on the ground floor of the Administration building.

These exhibits are entirely separate and distinct in their subject matter, but manage to engage audiences not just through physical materials, but also with preconceptions on living in the modern world while learning from the past. Linklater asked viewers who attended the opening of the exhibits to “think about all [they] did today,” and moreover, to think about life, the past and our conception of being present. Linklater closed by asking “for more days for all of us and … for blessings for everything here to work well, for good things to come from this event here.” The opening remarks of Strain’s exhibit concluded with a powerful song of blessings led by Linklater.

The two exhibits require active engagement with all of one’s senses to be able to understand the concepts visually, emotionally and spiritually, but most importantly, with awareness of your present self in relation to both the past and future.

Leave a Reply