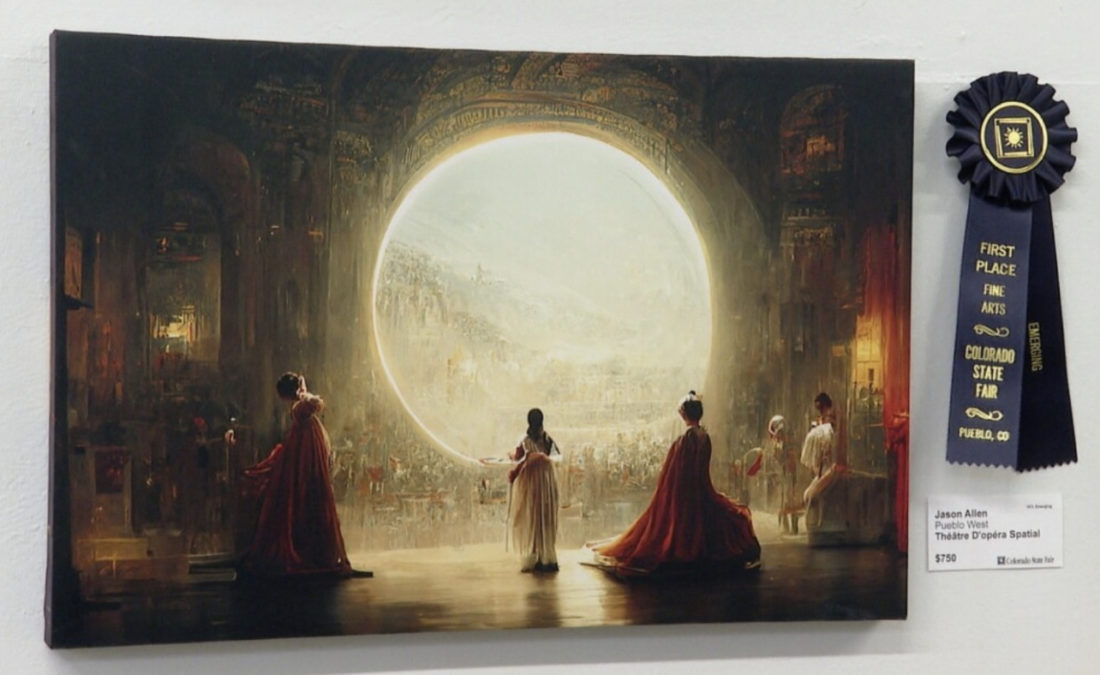

An AI-generated artwork won first place in a fine arts competition and sparked divided discussions about what defines art.

As artificial intelligence (AI) programs rapidly become more prominent in digital spaces, AI-generated digital art has also become widespread in the digital art community and its spaces. Emerging AI art programs like Craiyon (formerly DALL-E mini), DALL-E 2, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and WOMBO Dream all use the same operation of generating an art piece from a written prompt given by the user. After confirming the written prompt, the AI starts to process and analyze existing images of artworks that have been previously uploaded digitally. These programs then create and process their own product based on the written prompt and images related to said prompt.

”Within the next year or two, you’ll be able to make content in real time: 30 frames a second, high resolution. It’ll be expensive, but it’ll be possible. Then, in 10 years, you’ll be able to buy an Xbox with a giant AI processor, and all the games are dreams,” Midjourney founder David Holz said in an interview with The Verge.

This brings up the question of what counts as art and what doesn’t.

These AI art programs only generate new images by combining or altering already-existing images. The user has little control over the output, but can guide the AI with art styles and themes such as “Ghibli”, “Baroque” and “Steampunk” for their desired stylistic output. These styles and themes are based on existing art styles of artists and art movements with distinct visual themes and concepts that the AI is trained to analyze.

On Aug. 29, 2022, the Colorado State Fair held a fine arts competition with a category for the Digital Arts/Digitally Manipulated Photography. An AI-generated artwork, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial (Space Opera Theater) by Jason Allen, won the first place prize for the category.

It was only after Allen had accepted the prize that he revealed his artwork was created using a Discord-based AI art generator, Midjourney, then upscaled the image using AI Gigapixel which is a digital program used to enhance an image’s resolution in order to transfer the piece to canvas.

“Rather than hating on the technology or the people behind it, we need to recognize that it’s a powerful tool and use it for good so we can all move forward rather than sulking about it,” Allen said.

Both artists and non-artists alike responded with varied reactions, some viewing AI-generated art as unfair or lazy, while others were supportive of Allen’s use of the AI art generator and AI-generated art as a whole new art form. Discussions sparked surrounding consent and plagiarism about the ethical issues of these AI art programs taking from existing artworks and whether AI-generated works should be considered real art.

Are artworks that were produced almost instantly at the click of a button considered real art? Will AI art-generator programs replace real artists who rely on commission work to make a living?

AI art generators can certainly be a resource for brainstorming and pulling inspiration from generated images for personal projects, but with problems of plagiarism and nonconsensual use of artists’ works, one is left to wonder if it is a tool worth supporting and further advancing.

What these AI art generators may be able to do in the near future and how a digital space filled with AI-generated art could function are unclear, but the current possibilities of AI art are—like the images these programs can generate—seemingly endless, for better or worse.

With more of an emphasis on AI art comes more issues surrounding plagiarism and consent, as well as the rights artists hold with their own art. Since this technology is still fairly new and in development, there are little to no strict guidelines for AI-generated art and where its place is in the art community.

Leave a Reply