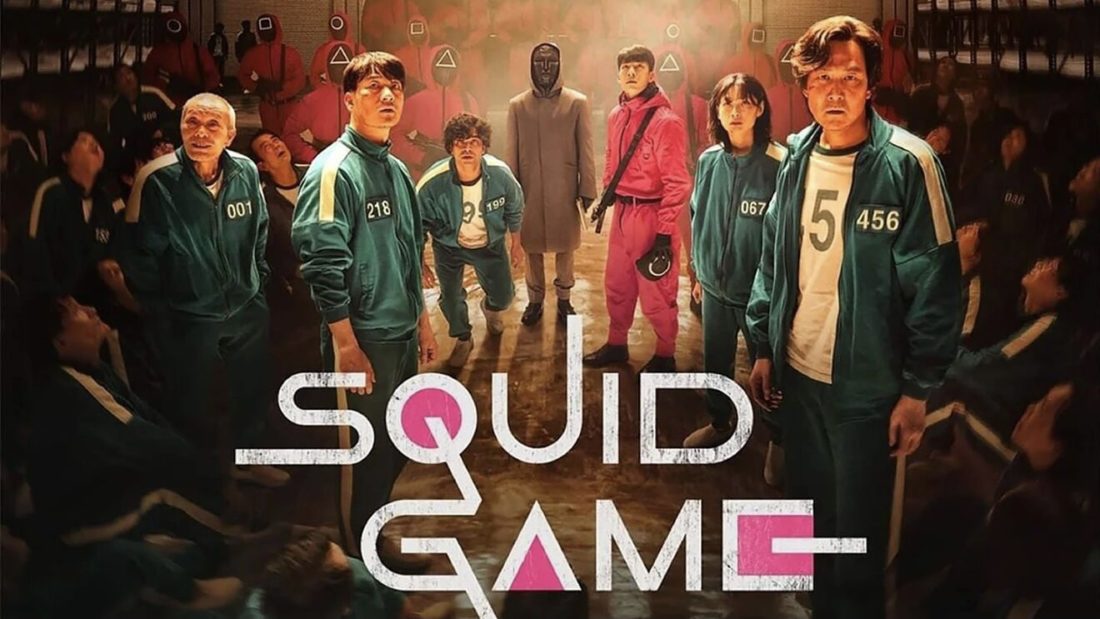

Squid Game is the most recent Netflix show to grip the world, setting records by becoming the most-watched original series on Netflix.

I found the show through social media. I kept seeing TikToks with theories about player 001 and how it was obvious he was in charge from the beginning of the show and Instagram videos of people trying to carve out shapes from melted sugar, which I would later learn were recreations of the Honeycomb Game. Those intriguing videos piqued my interest, and with the recommendations from family and friends to watch Squid Game, I knew I had to check it out.

Squid Game is a show about 456 people who are in desperate need of money who are brought to a large facility and forced to play children’s games such as hopscotch or marbles. If someone loses a game, they are instantly killed.

As it is later revealed, the games were created by ultra-wealthy individuals who had gotten bored with traditional entertainment and decided to create a game where they bet on the lives of the poor. Desperate poor people are treated as mere means towards entertainment, at the cost of their lives, by rich elites.

The main characters include Seong Gi-hun, a man heavily indebted due to his gambiling addiction, Abdul Ali, a Pakistani immigrant, Cho Sang-woo, a heavily indebted businessman who attends Seoul National University and Kang Sae-byeok, a North Korean defector.

While I ended up cheering for many of these characters, I knew in my mind that only one could survive. That curiosity brought me back episode after episode.

The show is reminiscent of other dystopias like the Hunger Games and provides similar critiques of social inequality like The Platform. I really enjoyed the critiques these films had about the ultra-wealthy, and Squid Game provides a similar argument.

I thought one of the most interesting aspects of the show came in episode two where, after finding out that they will die if they lose and seeing over 200 people killed, all 201 remaining players left the game. However, when given the option, 187 chose to come back. I tried to figure out why. Perhaps it was because of a realization of how bad life outside the game really was, the feeling of worth the game provided or the romanization of the games, but in the end, most players thought certain death in the game was better than living outside of it.

The show also provides a unique look at the lives of those in the lower socio-economic classes. Because of my upbringing in a middle-class home, I can sometimes forget that people feel abandoned and struggle all around the world. Squid Game provides insight into the harsh reality of capitalist cultures that focus intensely on status—so much so that people at the bottom of the social hierarchy are forgotten, to the point where 456 people can participate in Squid Game and go missing without anyone trying to help.

I think this show garnered so much popularity because of its novelty and the virality of simple, fun-looking games. The gamemakers force individuals to play children’s games such as Red Light, Green Light or the Honeycomb Game, which involves trying to carve out a shape from melted sugar and baking soda.

After watching Squid Game, I was tempted to play these games—especially the Honeycomb Game—and I couldn’t help but watch the many Instagram videos about it because of how satisfying they are, even though I knew, beforehand, what would happen.

While the games themselves are such a minor aspect of the show, they represent the majority of online interest. However, some of Squid Game’s popularity can also be attributed to the rise in consciousness related to economic inequality. As suggested by Sung-ae Lee, a lecturer of Asian Studies at Macquarie University, the games are also analogies to real-life experiences, as they represent stories of social aspiration and limited social mobility.

To me, Squid Game is also just a gripping show. Without spoiling the ending, I really understood why the winner chose not to spend the money, as the game took away his friends and family. I think the writers were implying that riches are not worth the sacrifice of meaningful connection with others. I felt that if he spent any of the money, he would be absolving any wrongdoing by the gamemakers—455 lives is not worth 45 billion won.

If you enjoyed watching The Platform, Parasite or the Black Mirror episode, “Fifteen Million Merits,” I would recommend watching Squid Game as it touches on similar themes while also being wildly entertaining.

—

This op-ed was written by a University of Saskatchewan undergraduate student and reflects the views and opinions of the writer. If you would like to write a reply, please email opinions@thesheaf.com. Simon is a third-year undergraduate student studying political studies.

Photos: As Credited

Leave a Reply