Anthony Huynh recalls one interview in particular in which a temporary foreign worker told him “thank you for talking to me.”

“I’m honoured, right? But at the same time, it also shows me that it’s not right,” Huynh said. “There needs to be systemic and structural changes.”

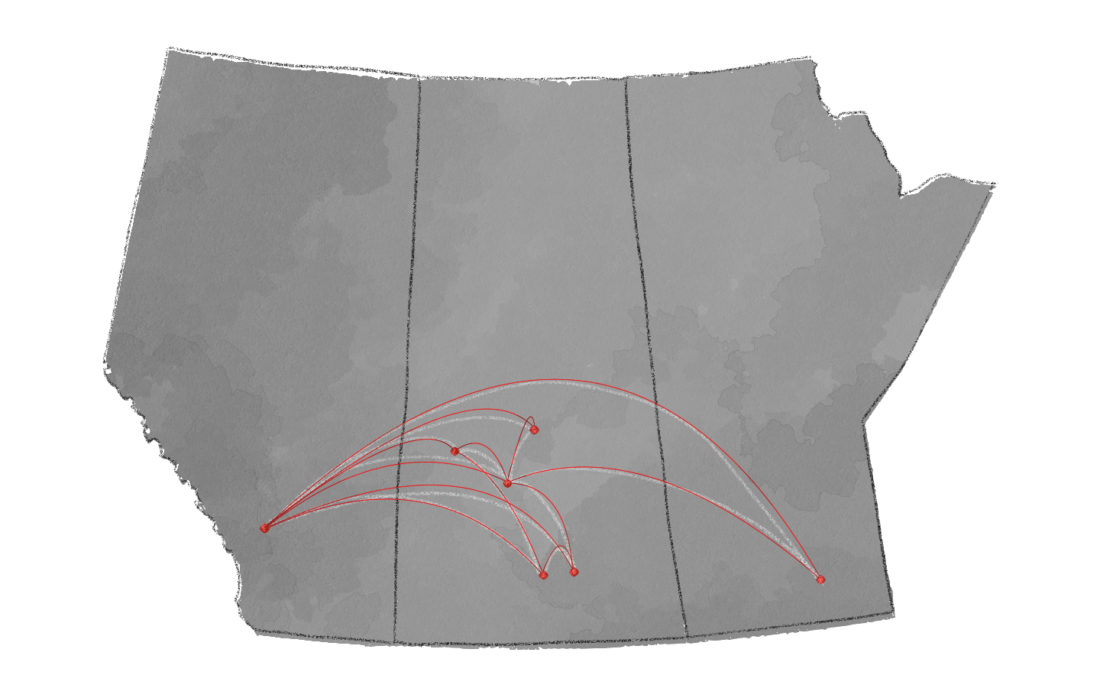

Huynh’s interview was part of a larger project to establish a network of support for temporary foreign workers (TFWs) across Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta. This project was led by the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society (CCIS) and funded by Employment and Social Development Canada following a series of COVID-19 outbreaks on farms in the spring of 2020.

“[Employment and Social Development Canada] identified that temporary foreign workers, particularly those in the agricultural sector, are disproportionately vulnerable to COVID, and also particularly important in helping secure Canada’s food supply chain,” said Jocelyn Davis, who wrote the CCIS’s project proposal to secure their funding.

Jessica Juen is the program manager for the CCIS’s Prairie-wide support project. She says that the decision that TFWs make to come to Canada is out of necessity.

“Foreign workers come here for one reason and for one reason alone. That is, to earn money for their family because they are the breadwinners in the family,” Juen said.

Juen says that the CCIS’s outreach to TFWs began at the airport, where TFWs were welcomed and given a package containing information on COVID-19 prevention. The CCIS also helped ensure that basic needs were met while employees were in quarantine, such as providing them with short-term housing and culturally appropriate food.

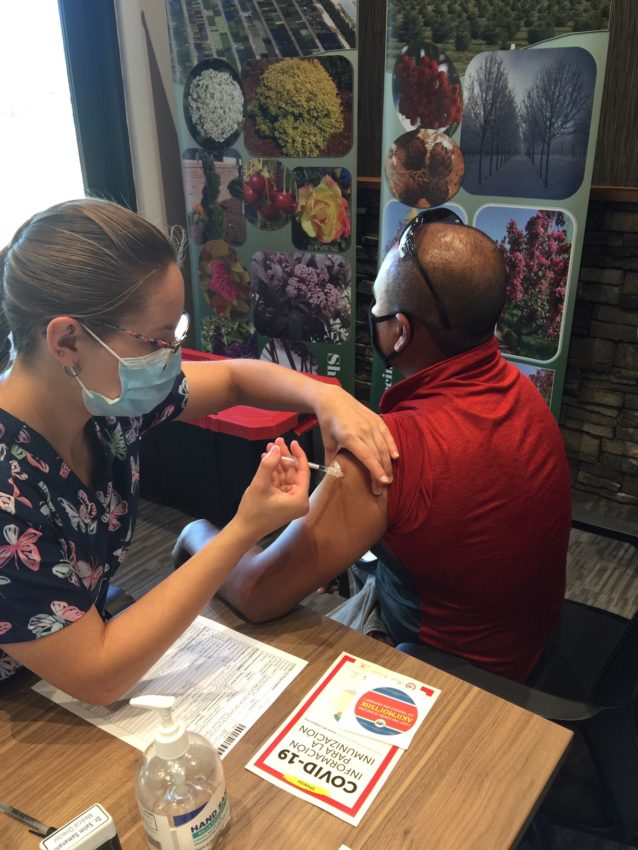

Juen and Davis say the CCIS has also provided a mobile COVID-19 vaccination service on farms and hosted hamper drives, where they distribute food and information about vaccinations.

“There are employers who are challenged to have the workers actually go through the vaccination simply because some of the employers, they’re busy. They’re a small business and this is a very short summer for them to be working,” Juen said.

Juen and Davis say that equivalent projects supporting TFWs were funded in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, but that there are particular circumstances in the Prairie provinces that affect TFWs differently. Namely, with a lesser population spread over a large geographic area, access to support services, transportation and technology is greatly variable.

“We are being very strategic and systematic in how we’re conducting outreach and how we’re communicating with employers,” Davis said, “so that no matter where a temporary foreign worker is, across Alberta, Saskatchewan or Manitoba, they’re able to receive very comparable services, and that they can do it without barriers.”

Juen says that although COVID-19 created obstacles in their work at the CCIS, it did not impede their ability to serve TFWs. Instead, their services became busier than ever before.

In other communities, however, project partners had varying experiences.

Annette McGovern is the Executive Director for the Battlefords Immigration Resource Center, one of the CCIS’s project partners. She was responsible for coordinating outreach across the region comprising Meadow Lake, the Battlefords and Kindersley.

McGovern says that operating in a large area with several small rural communities made communication especially difficult.

“Because of COVID, we had to be on the phone, and we had to have connections in each community, in each small community in between. And we were just trying to keep track of everybody and make sure everybody was all right, or if we’d missed anybody,” McGovern said.

Additionally, many TFWs in rural areas lacked internet access, and most communication had to be done through the employers, who were not always welcoming.

“That was the hardest part,” McGovern said.

Kaytee Edwards is the team lead for the TFW program at the Saskatoon Open Door Society, another CCIS project partner. She also says that the majority of TFWs they were able to reach were urban-based. While they physically visited farms when possible, COVID-19 safety measures often prevented this.

“We’re really hoping that [the project] does get extended, and if it does, then that means that the next year, when these folks come back, they now know that there’s a place that they can go to,” Edwards said.

Niña Reynolds is the manager of the Community Connections Centre at the YWCA Prince Albert, also a CCIS project partner. She says the YWCA’s capacity to reach agricultural workers was also limited, but funding from the CCIS partnership enabled the YWCA to spread word about its existing TFW support program.

“This has really helped us reach out to temporary foreign workers more, and actually have them come to us for assistance, because some of them didn’t know that we [help] temporary foreign workers,” Reynolds said.

As part of the YWCA’s TFW support program, Reynolds says that they provide financial support to TFWs for urgent needs, such as food and utilities, but that their capacity to do so is limited.

“We do refer them to financial institutions if that’s one of the [things] we can help them with, but the financial support itself, we don’t have funding. So, if we continue this particular program, [more funding] would really be a great help to the temporary foreign workers,” she said.

While much of the work done by project partners in the tri-provincial program served the health and safety needs of workers, another purpose of the initial project was communication.

“We recognize that temporary foreign workers, they are often a little bit more isolated because they don’t have those deep roots in a community because they’re not there permanently,” Davis said. “Sometimes they only really have access to the people that they’re working with, but they are members of the community and that isolation was another priority for us to be able to address.”

This is what Anthony Huynh’s work addressed.

Huynh was hired by the Manitoba Association of Newcomer Serving Organizations, another project partner of the CCIS, to conduct in-depth interviews with TFWs.

“I think the work that I’ve been doing just as a coordinator, in terms of connecting with them, providing them referral support, and just hearing them, listening to them, I think that also has been important,” Huynh said.

Huynh says he tries to build a rapport with his interviewees to help them feel at ease. Being a person of colour and having an immigrant family background himself, he says that “having those shared experiences is really important.”

“I really think it’s important that if you’re working with the community, you should have someone from the community. I think that I have a team who saw the importance and value of having a person of colour doing this type of work,” Huynh said.

Reflecting on his parents’ struggles as refugees in Canada, Huynh says that the interviews have highlighted how several circumstances combine to make TFWs susceptible to abuse. These include low income, the fact that their work permits are specific to one employer and the lack of permanent resident (PR) status, on top of other issues immigrants already face.

“With migrant workers, the fact that they don’t have [permanent resident status] just adds that layer of vulnerability,” Huynh said. “It’s troubling to hear that some workers, they just don’t feel like it’s safe for them to speak out, or because they’ve had experiences where other workers were fired.”

Huynh says it is ironic that the Canadian government acknowledges the necessity of TFWs in Canada’s economy while support for them remains inadequate.

“All workers should, upon arrival, receive status, or at least make the pathways to [permanent residence] more easy and offer family reunification,” Huynh said.

“They deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, regardless of their status.”

—

Sandra LeBlanc | News Editor

Images: As Credited

Leave a Reply