There is an international race to the COVID-19 vaccine, and researchers at the University of Saskatchewan are part of this crucial work during the pandemic.

The researchers at the university Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization-International Vaccine Centre are working on developing a vaccine for the SARS-CoV-2. Outside of that lab, there are also many other U of S scientists and researchers aiding the process in different ways. Although not in direct relation to the vaccine, the computer science department is helping biologists by organizing data via bioinformatics.

The Sheaf reached out to researchers working both directly and indirectly on the vaccine development. Dr. Darryl Falzarano, Dr. Tony Kusalik and student Zoë Parker Cates share how this research is impacting them and the global vaccine effort.

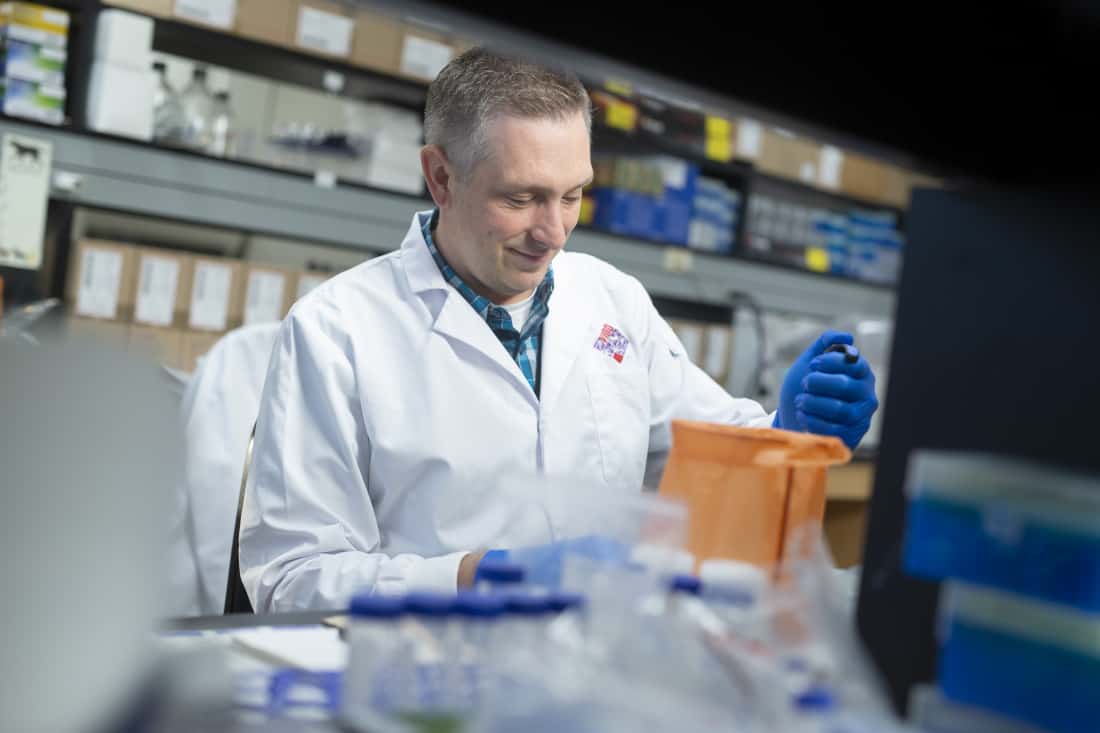

Dr. Darryl Falzarano, adjunct professor in the department of veterinary microbiology

Falzarano has a long history of working with infectious diseases. As a researcher of antiviral strategies for both Ebola and MERS-CoV, he says his experience suits what he is doing today.

However, now working as the principal investigator working with SARS-CoV-2, Falzarano notes that the current pandemic has been an unprecedented experience, making him and his team very busy.

“Trying to balance [everything] now is definitely a learning experience and trying at times,” Falzarano said.

Despite the busy schedule, Falzarano maintains hope in his work. He says that it “does get hard” since they have been working for many months now, but the team tries to stay motivated.

“People are excited about what we’re doing, and we are hoping that we have some sort of impact,” Falzarano said. “Our group remains very positive, very supportive.”

Falzarano tries not to dwell on the pressure, but he admits he feels it at times.

“I try to put that in a box and not worry about it. I compartmentalize that away because you need to focus on what you’re doing and not worry about external pressures,” Falzarano said.

Falzarano notes that VIDO-InterVac is one of many labs currently working on a vaccine. He says that many of these labs are large pharmaceutical companies, but no one knows which vaccine will actually work at the end of the day.

He says that “we are doing okay” despite not being in the lead internationally.

“They do their own thing, we do our own thing. We all have different capabilities,” Falzarano said. “And that’s fine.”

Falzarano predicts a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine will come out either in late 2020 or 2021, even though most vaccines take ten years to be developed.

“That’s unbelievable. That has never happened before,” Falzarano said. “I think the likelihood of there being multiple approved vaccines is very high. And that’s never happened before.”

Falzarano says that the current pandemic “shows the importance of supporting research all the time.”

“The importance of having the capacity in a country to respond on your own is important and you don’t have that without supporting research all the time in these areas,” Falzarano said. “It’s important to have that forethought to be preparing for things that don’t exist yet.”

Falzarano believes that the work being done in the lab lives up to the U of S goal of being “the university the world needs.”

“It’s exciting to be working in this area. It shows that VIDO-InterVac and the University of Saskatchewan can have some role in the world, ” Falzarano said.

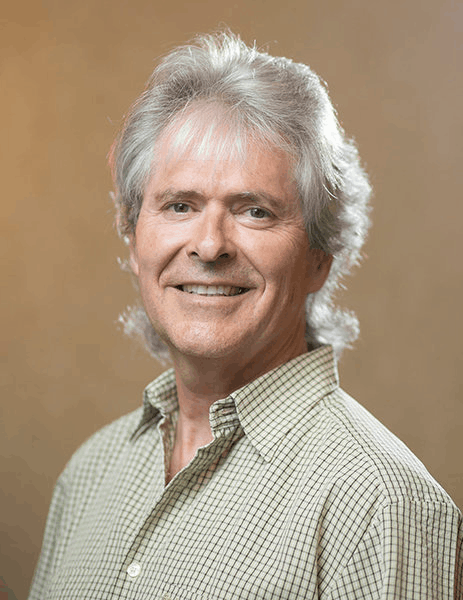

Anthony Kusalik, director of the bioinformatics program

For computer science professor Tony Kusalik, this pandemic has brought a whole new meaning to his research.

The work done by Kusalik’s bioinformatics research team is not only meant for the current pandemic but also for potential similar crises in the future.

“When COVID-19 appeared, we already had … a lot of ideas that we could simply take off the shelf and continue working with and working on, which was really advantageous,” Kusalik said.

Kusalik says that while the general public might be content with having a working product, the situation is different for biologists, who want to know the details of why the product is or is not working, among a plethora of other questions.

Such questions are necessary when it comes to the complex process of understanding immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in mammals.

Kusalik is part of the fascinating work being done by U of S researchers with microarray technology. The premise of their research involves a microscope slide with thousands of spots on it. Each spot contains pieces of protein molecules, more simply known as peptides, and the entire slide consists of copies of these same peptides. These peptides evoke a response from the immune system of an animal.

“The entire thing is called an epitope array,” Kusalik said. “What we do is you have a bunch of … peptides on this array, to which potentially there could be some sort of immune response.”

To check if there is an immune response, the researchers take a blood sample from a target organism such as a hamster and the immunological molecules that are targeting specific epitopes will react with the epitope on the array, says Kusalik.

The next part involves determining whether any immunological molecules that are targeting certain epitopes react with those epitopes on the array. The end result is a massive matrix of spots, where each spot’s luminosity is measured by intensity to determine to what degree the immunological molecule reacted with the epitope.

This is the part where biology meets computer science and statistics — also known as bioinformatics. Kusalik explains the relevance of the field in biologists’ work.

“When you scan one of these microarrays all you get is a spreadsheet full of hundreds to thousands of intensity values, just a great big huge matrix of numbers. And so the biologists … turn to us to try to help them understand what’s going on,” Kusalik said.

“We do the pre-processing of the data, we do various kinds of normalization techniques, we do various kinds of analysis, visualizations, so that they can get a good picture.”

Beyond the data, Kusalik says that this research has made him more appreciative of the applications of bioinformatics.

“It’s very gratifying that you are doing research that really can make a difference and help people,” Kusalik said.

He adds that sometimes researchers end up in a situation where they question the practical applications of their work. In studying immune responses to COVID-19, that is not the case.

On a broader scale, as international competition increases in developing a vaccine, Kusalik says he does not feel pressured in his research and he is amazed by how much people are co-operating at this time.

“One of the things that was identified or recognized early on is that by co-operating, we were going to find solutions to this problem much, much quicker,” Kusalik said.

Although he is eager for a solution to arrive, Kusalik is cautiously optimistic.

“There are some really, really smart people developing some very ingenious ways to deal with COVID-19,” Kusalik said.

“I’m sure that the general public will see just the tip of the iceberg as far as what eventually makes it to their drugstore.”

Zoë Parker Cates, student researcher in the bioinformatics program

When Zoë Parker Cates was sending out computer science job applications late last year, she never anticipated the hard-hitting arrival of COVID-19. Now, she is working on a software that could have applications in pandemic research.

Parker Cates’ work focuses on a Python program called Epiphany, which will organize data so that biologists can derive meaningful information from it.

She says that centralized data-processing methods in programs such as Epiphany are important for biologists.

“A lot of the time that means they have to hand the data off to outside parties, other companies who will process it for them and then give them back the results,” Parker Cates said.

Some of Epiphany’s features include cluster analysis, normalizing data, producing plots and helping “people doing the research to think about where they should take their next steps.”

Parker Cates is excited to participate in this type of work, as it brings a new perspective to her studies that goes beyond assignment deadlines and exams.

“One of the things for computer science students is sometimes … we’re writing code just to get that code done and just to have an assignment to hand in at 6 p.m. on Friday, because that’s when it’s due. It doesn’t matter what it looks like as long as we get the marks,” Parker Cates said.

“Here I’m writing something that hopefully we want people to be able to use for quite a while after it’s done so it’s exciting and it puts me in a different frame of mind when I’m writing the code.”

Despite the elation that comes with such an opportunity, it is not without its hardships. Parker Cates says that the most difficult part of doing the work is that she is doing it remotely.

“This is a new experience for me, actually doing some work in my field for the first time,” Parker Cates said. “Trying to access computer science resources from my own computer, having meetings online… The hardest thing is [it’s my] first time doing this, working from home in the middle of a pandemic.”

However, Parker Cates has high hopes for her work in Epiphany.

“My hope is that everybody will be able to use it, [that] it’ll be user friendly … and that it lowers the access barrier for using computer science methods on biological data,” Parker Cates said.

Parker Cates says this work has kept her motivated in even the dimmest of times and has helped shape her personal growth this year.

“I think that something that a lot of students are struggling with this term is the motivation to keep working from home and watching asynchronous classes… For me, working on this project has been really motivating and it’s been really helpful,” Parker Cates said.

“This project has definitely given me a lot of motivation to keep working and keep pushing through the last little bit of my degree because I know there’s some really interesting things I can be working on.”

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the name of one of the university researchers. Zoë Parker Cates’ last name is Parker Cates, not Cates. We apologize for this error. If you spot any errors in our articles, please send us a message.

—

Wardah Anwar | News Editor

Fiza Baloch | Staff Writer

Photo: Supplied | Trenna Brusky

Leave a Reply