Writing about music is difficult. When writing about film, you have a plot to describe and performances to evaluate. If all else fails, you can haphazardly throw around terms like “shot composition” until you fashion the general shape of a criticism.

For someone who isn’t trained in musical theory — someone like myself — you generally have these vague ideas about which music is good but a harder time articulating what’s good about it. This is why, when I write about music, I tend to adopt an almost phenomenological approach. I focus on the textures — the way music feels and how we relate to it on an immediate sensory level.

Loveless is simultaneously praised for its warm dreamy atmosphere and remembered for a live tour that was so earth-shatteringly loud that it caused the music press to accuse them of criminal negligence. It’s a record in which limitless possibilities for new sounds are just waiting to be discovered.

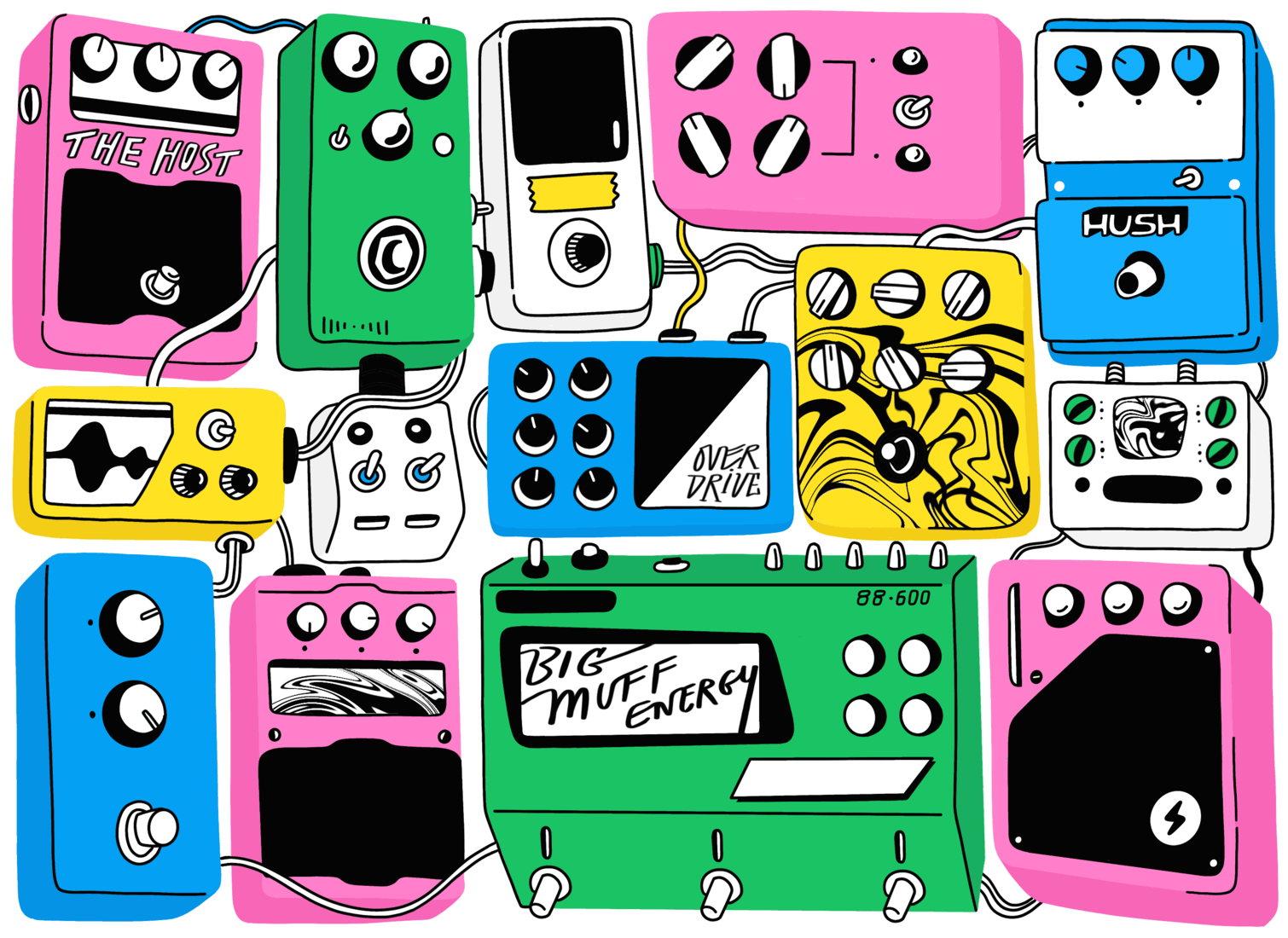

I’ve always been drawn to texturally dense music, and no genre has a sonic palette as rich and evocative as shoegaze. The style relies on effects pedals for most of its sound, but the genre’s hallmarks of carbon-burst drumming, clean bass lines and airy vocals buried deep in the mix equally contribute to a rewarding and dense sound that really resonates. Originally, the genre was billed as “the scene that celebrates itself ” by the British music press to describe the sense of community felt by the effects-pedal-obsessed architects of the genre. The term shoegaze, which developed later on, refers to the way that audiences visually perceived musicians playing in the style.

It conjures the image of a guitarist with his head cast down, nonchalantly strumming while monitoring the timing for each new effect change. He appears to be staring at his shoes, but in reality, he’s concerned with the extension of his instrument — a carefully curated collection of guitar pedals.

“I come to shoegaze as looking at it from a psychedelic perspective, but some of the other members of the band are coming at it from a grunge sort of deal, like Christian, the other singer in the band — one of his biggest influences is Kurt Cobain.”

— Nic Nibbs, musician for Bicycle Daze

More than any other band, early British shoegaze act My Bloody Valentine had a massive impact on what the genre sounds like. The basic textural building blocks of reverse reverb, fuzz and delay are all used in their 1991 masterwork, Loveless.

It’s a record that sounds unlike anything else, a self-contained world of sound where pure sonic energy is bent into new shapes that alternate between unnatural and ethereal.

Loveless is simultaneously praised for its warm, dreamy atmosphere and remembered for a live tour that was so earth-shatteringly loud that it caused the music press to accuse them of criminal negligence. It’s a record in which limitless possibilities for new sounds are just waiting to be discovered.

Some people heard the latent influence of 60s psychedelia, some heard the future of heavy music, and others heard jangly, floaty pop music buried under everything else. I’m sure there are countless other things waiting to be heard in there as well.

Despite their legendary status and influence over a lasting genre, the release of their long-awaited follow-up mbv took 22 years to materialize.

During this stretch, other bands took the melodic elements of the genre and expanded on them, further developing the dream-pop and space-rock sub-genres. Other bands like Drop Nineteens and Swervedriver built a grungier, heavier sound from the blueprint.

More recently, the genre has calcified around a few major sounds. Experimental ‘blackgaze’ acts like Deafheaven pissed off black-metal fans by mixing blast beats and death growls with decidedly not-metal effects pedals while bands like Nothing and Whirr brought a hardcore punk influence to the genre. Shoegaze is everywhere in independent music right now. It’s had an unmistakable impact on metal and punk but also on indie-pop bands like Japanese Breakfast and Beach House.

To find out what it’s like to play this kind of music, I spoke to Nic Nibbs, a student in arts and science who plays in both local shoegaze act Bicycle Daze and garage-rock-influenced band the Gargyles.

Nibbs is currently preparing for two upcoming projects: a Bicycle Daze show on March 15 at Amigos Cantina and an EP with the Gargyles. In Bicycle Daze, he alternates between guitar, keys and vocals as needed. While Nibbs tends to think of Bicycle Daze as a psych-rock band, he also fully embraces the label of shoegaze.

“I call us psychedelic rock, but I think shoegaze applies to us, too. Even just like the origin of the word is exactly what we do — we stare at our shoes,” Nibbs said.

I found this interesting, as I’ve always heard something a bit more aggressive and punkoriented in shoegaze music. I then asked him about where other members of the band are coming from in their appreciation of the genre.

“I come to shoegaze as looking at it from a psychedelic perspective, but some of the other members of the band are coming at it from a grunge sort of deal, like Christian, the other singer in the band — one of his biggest influences is Kurt Cobain,” Nibbs said.

Nibbs’ vocal influences are a bit outside of shoegaze orthodoxy. He finds inspiration in unlikely places such as soul music, and he has a strong appreciation for Freddie Mercury and the discography of Queen.

“I definitely come from a bit of a soul background. I’ve always sort of considered myself a soul singer that sings rock — that’s where my base is. Even though that’s not necessarily the way that I sound, it’s more my mindset,” Nibbs said. “As far as vocal tendencies, I love Al Green [and] Freddie Mercury is huge for me. Queen was one of my first big bands.”

Outside of personal influences, he identifies the early MBV records as a source of direction for the band.

“There’s definitely a few bands — My Bloody Valentine, for sure. I’d had a little bit of exposure before, but I really got into it after meeting Christian. And not so much for me, but I know … a really big link between a bunch of guys in the band is Jimmy Eat World,” Nibbs said.

Aside from influences, I also asked Nibbs about his gear set-up. He estimates that a starting set-up would cost around $1,000, including a guitar, keys and effects, but he also stresses the importance of assembling gear on a budget.

“I’m definitely one of the more cost-conscious members of the band. I’m really into finding the deals. Before the band, I was still exploring my place as far as pedals went. I had a limited pedal board — like four or five, just the basics. The rest of the band, they haven’t put too much money into their pedal boards because they’ve already spent like a million dollars on it,” Nibbs said.

Nibbs’ advice for aspiring musicians is to avoid buying expensive and unnecessary gear when starting out and to focus on learning to use affordable alternatives before jumping into advanced effects.

Nibbs does all of the effects for his keys and vocals with the onboard-effects station on the keyboard. For his pedal set-up, he has three main pedals: one for delay, one for pitch shift and one for fuzz. He describes how the pitch-shift pedal contributes to his sound on guitar.

“I use pitch shift a lot as well. It’s another hallmark of my sound. It adds this shimmer, so you play a chord, and it plays the same notes but three octaves higher. I always think of the top of a lake in the moonlight, and it’s just shimmering,” Nibbs said.

Of the three, the pedal he was the most excited to talk about was the fuzz. Fuzz is one of the most essential parts of the shoegaze sound, and Nibbs invested in a unique pedal for this effect.

“I have a custom-made fuzz pedal called “the catalyst” that I bought from Paul’s Boutique in Toronto. That’s like my baby — it’s the most expensive pedal I’ve bought. There’s nothing else like it — it literally feels like I’m walking a pack of rabid dogs,” Nibbs said.

When I decided to write this, I knew it was going to be a personal essay on some level. Getting a chance to learn a bit about the craft and technical knowledge that goes into making this kind of music was absolutely the highlight of working on this piece. Seeing the level of thought that goes into producing sounds that seem so effortless and immediate is fascinating.

Shoegaze music has always carried a nostalgic, evocative quality for me. It’s easy enough to describe the sounds that are produced in terms of texture — the tones can be warm, fuzzy, frigid or heavy — but the way in which they carry the listener is less easy to describe. Textural buzzwords only get you so far. Words don’t do it justice, and for a writer, that can be kind of frustrating.

But for me, that’s always been the appeal: the way in which words fall short of describing the kind of experiences that music can elicit. Good music should make you feel something that’s both completely new and oddly familiar.

As long as people are staring down at beat-up Converse chucks and conjuring massive walls of sound from thin air, I’ll keep trying to translate that simple feeling into language, and my words will fail it.

You can find this playlist on our Spotify, or follow The Sheaf Publishing Society on Spotify for all of our playlists.

—

Cole Chretien / Culture Editor

Graphic: Jaymie Stachyruk / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply