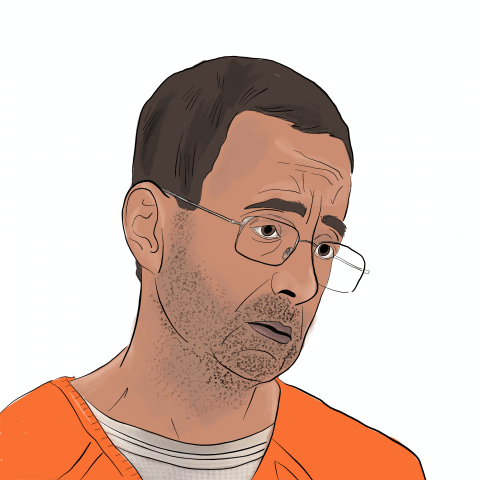

Since the first public statements against Dr. Larry Nassar were made in late 2016, the world has been shocked by the horrific extent of the abuse he carried out during his two-decade span as the USA Gymnastics team doctor.

As of Feb. 2, the number of Nassar’s victims is up to 256 — making him one of the most prolific sexual predators in history.

If we direct our attention away from the deflated orange figure on the news, the case raises some important social questions — perhaps the most obvious being how someone was able to do this for so long without being caught.

In order to prevent this kind of abuse, we need to understand the factors that allowed it to occur. Despite the uncomfortable nature of the case, athletes, coaches and medical professionals around the world have been participating in a discussion about just that — a discourse focusing on trust and accountability in the unique environment of sports medicine. The U of S has been no exception.

Dr. Liz Harrison — sports physiotherapist, professor and associate dean of the School of Rehabilitation Science at the U of S — talks about some of the precipitating factors that can lead to cases like that of Nassar.

“When I first heard [about Nassar] on the news, I was taken aback — I thought things were so much better. We’ve made some great inroads over the years, but there are still problems,” Harrison said.

Harrison has practiced for over 40 years in the field of sports physiotherapy and has worked for a variety of institutions over her career. She has also had the opportunity to work closely with local, provincial and Olympic athletes. As a former physiotherapist for Canada’s synchronized swimming and gymnastics teams, Harrison is able to offer a unique perspective on the case.

“I am consistently amazed at how much stress is placed on young athletes — even at local, high school and provincial levels,” Harrison said. “Gymnasts are often younger females, and it can be hard for young athletes to cope, physically as well as emotionally. There are significant stresses.”

The sport of gymnastics straddles the balance beam between athleticism and artistic performance — it’s incredibly demanding and fiercely competitive in nature. The amount of dedication required to reach the Olympic level is nothing short of heroic.

“Stress-factors, combined with the physical demands of the sport, lead to more injuries — and thus, more exposure to health professionals,” Harrison explained.

It was in this environment that Nassar was able to earn the trust of his patients, before taking advantage of them.

The pressures of high-level competition clearly signal the need for high standards of professionalism in sports medicine, with an emphasis on consent and understanding. According to Harrison, this is a commonly held belief.

“I’ve, to my knowledge, only worked with ethical professionals who understood that we’re privileged to be in a position of such trust. With that trust comes a huge responsibility,” Harrison said.

When Harrison practiced sports physiotherapy, she often did so as part of a large health-care team — a system which provides built-in accountability, increasing the patient’s safety. This approach is considered common practice, but Harrison came across a number of exceptions in her career, including situations where only one or two physicians were solely responsible for a team.

“Generally, these were smaller teams, limited by money or a lack of available physicians,” Harrison said.

The vast majority of medical professionals are clearly devoted, compassionate people, but every so often, someone like Nassar can slip through the system.

The pain present in the testimonies of the USA Gymnastics team members is undeniable, but just as evident is the role that competitive sport has played in fashioning these determined and incredibly brave young women, survivors of abuse that no one should ever have to endure.

—

George-Paul O’Bryne

Graphic: Lesia Karalash / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply