Intimate partner violence occurs within LGBTQ communities, but is often ignored or overlooked. In a world where much of the attention tends to focus on heterosexual relationships, it is important to understand the risks and issues that affect the queer community.

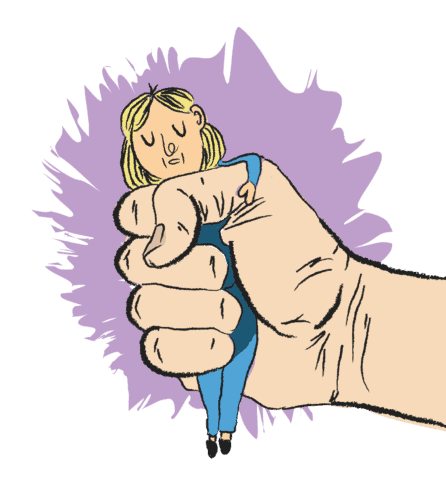

Valentine’s Day is a holiday that glorifies the positive aspects of romantic relationships, but not all relationships are always healthy. Intimate partner violence is a term that describes all violent action that occurs within romantic or sexual relationships, including physical, emotional, psychological and sexual violence. IPV is often viewed within the context of heterosexual, monogamous relationships, but it is as much — if not more — of an issue within LGBTQ relationships of all forms.

According to a 2010 study from the Centre for Disease Control, 26 per cent of gay-identified men and 37 per cent of bisexual-identified men reported experiencing  some form of IPV, while 44 per cent of lesbian-identified women and 61 per cent of bisexual-identified women reported the same.

some form of IPV, while 44 per cent of lesbian-identified women and 61 per cent of bisexual-identified women reported the same.

There are factors that can increase the risk of an LGBTQ person’s exposure to IPV. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, LGBTQ people have higher rates of poverty, addiction and mental illness — all factors that contribute to an increased risk of IPV.

It is impossible to separate queer IPV from other parts of intersectional identity. Certain kinds of abuse can be affected by factors unique to an LGBTQ identity, including homophobia, lesophobia, biphobia and transphobia. More specifically, partners may deny or target a person’s claim to their identity, such as purposely misgendering a trans individual or denying the existence of a bisexual person’s sexuality.

Regardless of the community it occurs within, many of the signs of IPV remain the same. Although there are obvious signs of physical abuse, the signs of emotional and psychological abuse can be much harder to detect.

Examples of emotional and psychological violence include unfair accusations, isolation from family and friends, humiliation, threats of physical assault, controlling financial resources, name-calling, blaming and gaslighting. Some of these are illegal and others are not, but all are wrong and unhealthy.

There is no easy solution to IPV within LGBTQ communities. However, there are strategies that can help service providers better support queer victims of IPV. These strategies include creating a queer-friendly counselling environment, using gender-neutral terminology and not making assumptions about a person’s sexuality or the gender identity of their partner.

Additionally, healthcare providers need to be able to provide LGBTQ specifiic resources to their patients and ensure that these resources — pamphlets, websites, etc. — use gender-neutral language and inclusive terms.

There are resources available in Saskatoon to LGBTQ individuals who may be affected by IPV. At the University of Saskatchewan, the U of S Students’ Union Pride Centre offers information and peer support in an LGBTQ-inclusive setting. The USSU Women’s Centre, the Help Centre and Student Health/Counselling also offer resources for those affected by IPV.

Within the wider community, OUTSaskatoon, a local LGBTQ-focused not-for-profit and community centre, offers multiple pillars of support, ranging from individual counselling to support groups to online information. Saskatoon Sexual Health is also a good option for gender and sexuality-inclusive resources.

No one should suffer from IPV alone. Although IPV within the LGBTQ community may be harder to identify and address, this means that we need to do even more to help.

—

Emily Klatt / Sports & Health Editor

Graphic: Lesia Karalash / Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply