MONICA GORDON

Imagine how frustrating it would be when you applied for university student loans in high school, if you were repeatedly put off and told that you were too young to know what career path was right for you to make such life-altering decisions.

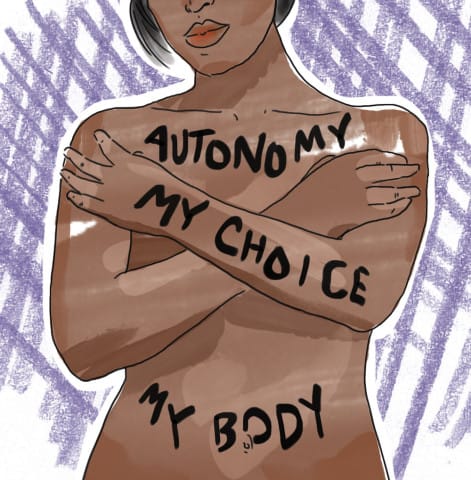

Rejection for these reasons is a constant reality for a small but growing number of people in Canada: women in their 20s and 30s who wish to choose sterilization as a way to remain permanently childless. While their choice may be unconventional, denial on these grounds is hypocritical and unjustified.

To get a tubal ligation in Canada, you need approval from a gynecologist and must attend mandatory counselling. This is to ensure you’re aware of non-permanent alternatives; you understand the procedure is permanent and you’re certain that sterilization is what you want. Most provincial health-care plans cover the surgery itself.

The biggest hurdle for childless women is that first step. They often encounter doctors who will dismissively refuse their requests, citing the reasons listed above. While the position of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada is that sterilization technology should be available to all Canadians, this is rarely the case for these women.

Many women put a lot of thought into their decision and know that they wanted to be sterilized for years. Bri Seeley, a writer for the Huffington Post, described feeling intense frustration at her doctor turning her down annually for six years. As she put it: “Why can’t I be the one to decide what’s best for my life?” Unsurprisingly, having multiple doctors reject your desires multiple times condescendingly is a very demoralizing experience.

Women who seek sterilization and want a say in what happens with their bodies are treated as if they couldn’t possibly know w hat they want, due to their youth and the unorthodox nature of their request. Sterilization is portrayed both as a permanent decision and something that these women will likely regret. However, neither of those things are necessarily the case.

hat they want, due to their youth and the unorthodox nature of their request. Sterilization is portrayed both as a permanent decision and something that these women will likely regret. However, neither of those things are necessarily the case.

Sterilization is technically permanent in that the reversal procedure is often unsuccessful and also rather expensive — and it’s not covered by provincial health care. However, sterilization doesn’t mean you can never become a parent. Unless a woman gets a hysterectomy, she could still be a candidate for in-vitro fertilization. Besides that, there are many children in the world who need a home. A woman who gets sterilized and changes her mind about children could always adopt.

The Guttmacher Institute, a non-profit organization that works to advance reproductive health, conducted a study on regret rates for female sterilization. They found that for childless women, the regret rate was only five to six per cent, regardless of the woman’s age.

To put that in perspective, the divorce rate in Canada fluctuates between 30 and 40 per cent. Given these statistics, it would seem that the women in question are more likely to regret getting married than getting sterilized.

Yet, when women in their 20s and 30s head to the altar, justices of the peace aren’t turning them away en masse because they’re too young to make such a life-altering decision.

This reaction would be seen as absurd in regards to marriage and it doesn’t become less ridiculous when applied to sterilization.

Despite youth being the most cited reason for rejection, even older women have difficulty getting sterilized. The Toronto Star interviewed a woman under the pseudonym “Tabatha” about her pursuit of sterilization. Tabatha had been asking to be sterilized since she was 25, but wasn’t given approval until she was 40. She “had to really push [her] doctor,” who was still reluctant despite the fact Tabatha was nearly past childbearing age.

This unwillingness to take these women seriously also has some potentially lethal side-effects. Anne Trate, a woman interviewed by the Chicago Tribune, has bipolar disorder and takes medication to keep it under control. To carry a pregnancy to term, Anne would have to go off her meds, which she thinks could put her life in danger. Her bipolar disorder is so bad that she’s “not even sure [she] could care for children if [she] had them.” Despite this, she’s been unable to find a doctor willing to sterilize her.

To deny these women sterilization because of their age or because what they want is different from the norm is unfair. Why is their choice not taken seriously? Voluntary sterilization doesn’t hurt anybody and it’s a huge disservice to treat these women like they don’t know their own minds. While there may be a few women who are impulsive, the mandatory counselling is designed to filter them out.

We are talking about adults trying to obtain the form of birth control that is best suited to their lives. While sterilization may not be something everyone wants, it’s in our best interests to let people decide how to live their own lives.

—

Image: Stephanie Mah/Graphics Editor

Leave a Reply