DAN LEROY

The Fulcrum (University of Ottawa)

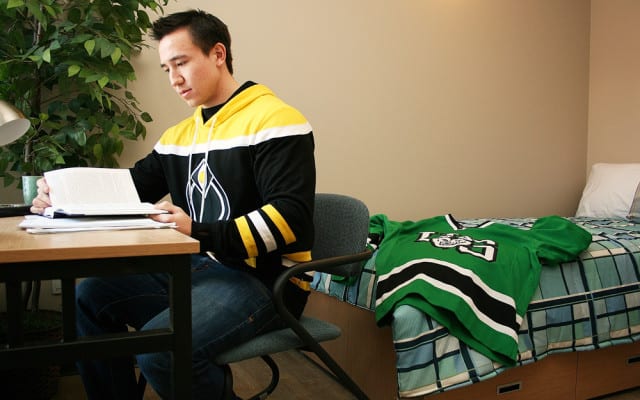

A new study is debunking the common misconception that students can’t be both athletic aces and academic savants.

OTTAWA (CUP) — The stereotype of physically gifted varsity athletes as academic dimwits is commonly portrayed by mainstream media. Some people simply can’t help but think, “These athletes just skate around a rink or hit a ball, so how smart can they really be?”

But according to a recent study by Jocelyn Faubert, a professor at the University of Montreal, top-tier athletes actually learn more quickly than the average student.

The study showed that professional athletes succeed not solely by being strong, physical powerhouses, but by possessing high biological motion perception — the ability to track multiple fast-moving objects simultaneously.

For example, two of the National Hockey League’s top scorers, Sidney Crosby and Martin St. Louis, are not the strongest or fastest players, but their ability to anticipate the play and know where the puck is going sets them apart from the rest.

“Biological motion perception involves the visual systems’ capacity to recognize complex human movements when they are presented as a pattern of a few moving dots,” Faubert writes in his study.

In his research, Faubert happened upon a trend that indicated athletes tended to be quicker and become adjusted to new patterns at a faster rate than the average individual. This led Faubert to conduct a study with CogniSens Athletics, a lab that has access to athletes in the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the NHL and Major League Soccer.

Professional athletes, as a group, have extraordinary skills for rapidly learning unpredictable, complex dynamic visual scenes.

Jocelyn Faubert, Professor, University of Montreal

Faubert’s study found, with almost no ambiguity, that the athletes studied learned more quickly than average university students.

This doesn’t mean that athletes are smarter than students in every way — to be smart can mean many things. Einstein was a brilliant physicist, but likely couldn’t throw a 50-yard touchdown pass.

Some intelligence relies on quick, instantaneous learning and hyper-focus, while other intelligence requires long-term concentration and rational induction. An NHL player, though, will generally be able to focus intently for the five to eight seconds necessary to make that outstanding play nobody else could have seen.

Félix Morin, a master’s of science student at the University of Ottawa and a member of four intramural hockey leagues, said being an athlete has a positive impact on his school work.

“Although [sports] takes time away from school work, I think it has a positive effect,” Morin said. “If being happy makes me more efficient at school and if doing sports makes me happy, then exercise is clearly positive.”

As to whether being a strong athlete on the ice makes someone a faster learner, Morin was skeptical.

“I don’t know if I am a fast learner or not,” he said, laughing. “I think I am quicker in some fields, but not as much in others.”

Faubert’s study highlighted that “professional athletes, as a group, have extraordinary skills for rapidly learning unpredictable, complex dynamic visual scenes that are void of any specific context.” It also found that athletes tend to have higher kinetic intelligence than the average student.

Now this is no reason for non-athletic university students to despair. Crosby or Alex Ovechkin might prove unable to carry out scientific experiments or lead a political debate in the same way many university students can. However, if students faced off against these world-class hockey players in a test of processing multiple events in a small period of time, the athletes would likely put the students to shame.

—

Photo: U of S/Flicker

Leave a Reply